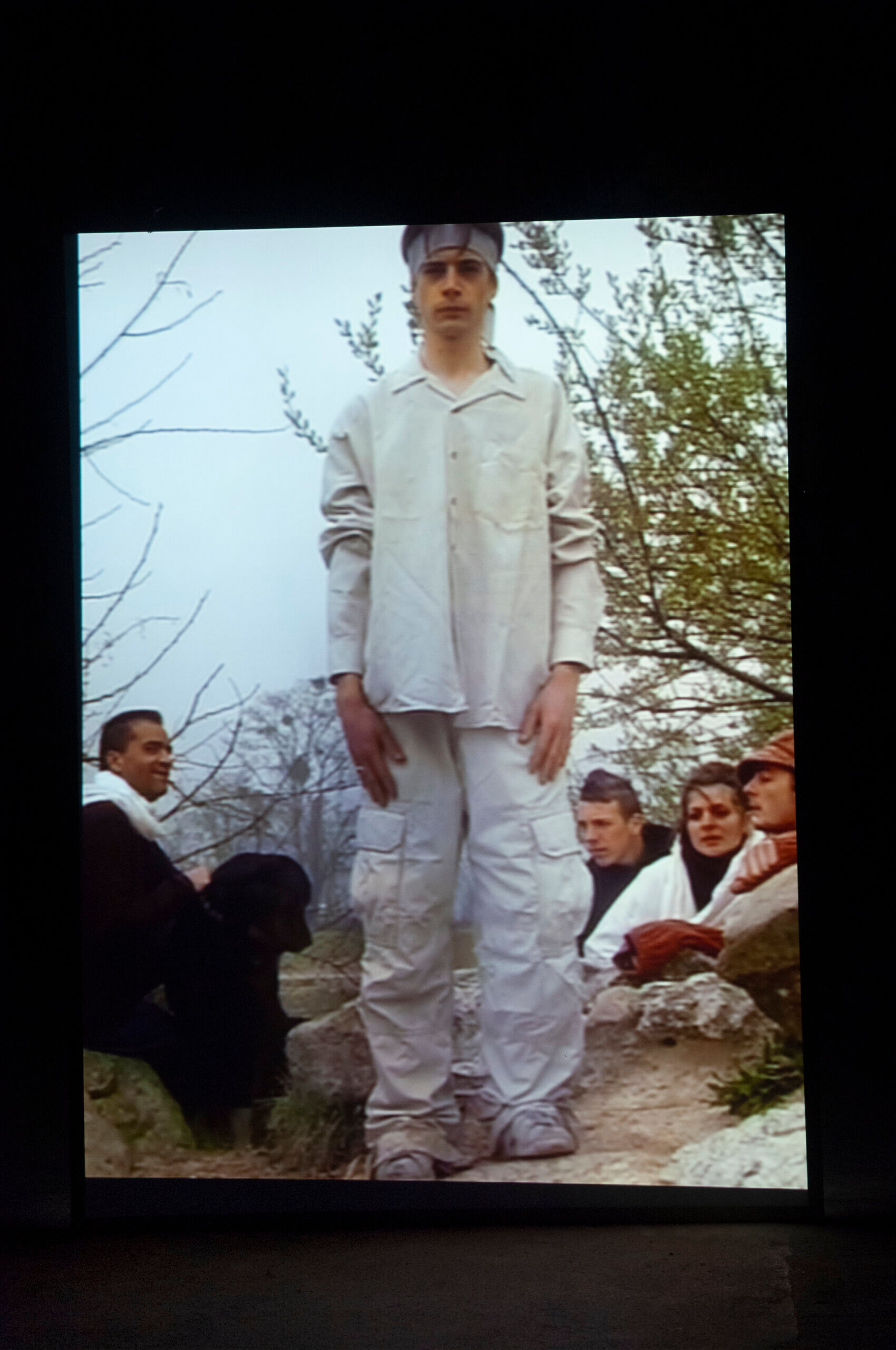

Gilles dumbly dwells as image alone.

Thierry Kuntzel

Gilles stands upright, a bit stiff, gaze vacant. He seems to bear his own imprisonment out in the open. The slight animation in the background – gazes crossing, a dog’s fidgeting (instead of a donkey in Thierry Kuntzel’s video) – form the murmuring of an animated and enjoyable existence, marking a minor gap between Gilles and his group of friends. Far from being excluded, he instead occupies the front and center, at the composition’s foreground. In a borrowed pose, he faces the gaze of representation (that of spectators in front of the picture or video on occasion), while aware that he is the object of the gazes (and perhaps, the discussion) of the group behind him composing a separate, dissident scene. This space between holds only exteriority.

As spectators inevitably recognize themselves in the group of extras observing Gilles with an air that is amused at times, distant at others, they are irresistibly led to deduce that Gilles represents the figure of the artist as an idiot, delighted to revive the celebration of genius and folly. Pierrot, formerly known as Gilles (1718-1719), has been so often associated with Jean-Antoine Watteau that it could seem intolerable and downright scandalous to cast doubt on this attribution, given the renown linking artist and work; and with this masterpiece, a sort of hyperbolic portrait of the painter would be lost, superlatively designating Watteau as its maker, whoever or wherever he may be. But looking at Pierrot or Gilles, we could very well be before a work that could quite accurately be titled Self-portrait, attributed to Watteau.

What becomes of the jester after the king loses his head? And what becomes of the useful idiot after the election? We might see the former pirouetting through Deligny’s garden, and hear the latter on the other side of the fence, calling for a resignation. It is of course necessary to be careful not to mix up idiot, imbecile, fool, moron, lunatic, simpleton, dupe, dunce, halfwit, etc. These figures characterize differentiated relationships with discourse and knowledge. They distinguish the difference in identity from oneself. They specify the art of rowing one’s boat, of occupying the first person singular, of believing oneself master of the language gripping us. They do not string together the real, the symbolic and the imaginary in the same order. In his essay on Pulcinella, Giorgio Agamben remarks that at the same time as Carlo Gozzi was removing this figure, which he judged redundant, from his theatrical fables (near the end of the 18th century), Giandomenico Tiepolo, in his Divertimento drawing series, was featuring this commedia dell’arte character alone, viewing him as encapsulating them all: “‘I am Pulcinella’ was his extreme profession of faith – that of all men, and thus mine as well. That is to say: the ‘me’ cannot live, Pulcinella alone can live. Living, making one’s life possible, may only mean – for Pulcinella, for all men – considering one’s own impossibility of living. Only then can life begin. Every autobiography, to the point where it becomes true, is a biography of Pulcinella. But Pulcinella’s biography is not a biography, it is only a Divertimento per li regazzi.”

In Watteau’s painting, Gilles is part of a troupe of actors, like his comrades. As indicated in the Louvre’s description, justifying the change in title, four usual commedia dell’arte companions to Pierrot can be seen: the doctor on his donkey, the lovers Leandro and Isabella, and the captain (Columbina is notably absent). The scene occurs between two performances. The actors have not yet taken off their costumes, or have gotten ready and are enjoying a break before getting back onstage. This shows Watteau’s tendency, shared with Fragonard, to paint ambiguous scenes, like a swing frozen in motion, which could very well be going up or back down. The same could be said for arrival and department in Pilgrimage to Cythera, and in a number of romantic scenes, in the gesture of an elegant woman to push away or draw in a seducer (itself a subjugated or consented gesture). The gesture can be seen once again, caught in its indetermination, with the donkey’s refusal to move forward, reflecting Pierrot’s impassiveness.

![Jean-Honoré Fragonard, <em>The Swing</em> [also known as <em>Les Hasards heureux de l'escarpolette</em>], 1767. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64,2 cm. The Wallace Collection, London. Source : Wikimedia Commons.](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Fragonard_The_Swing-scaled.jpg)

Kuntzel’s video Gilles (De l’obscur à l’obscure clarté), his final work, from 2007 (just as Watteau’s Pierrot was his own final work), slowing down bears a refusal that remains obscure. It is unmotivated. This refusal stretches over a slowing down that is not quite the same as that which, with the grace of an extreme slowness in the work of Bill Viola, effects an unveiling of the invisible in the visible. Nor is it entirely similar to what, in the work of Douglas Gordan, grazes the truth buried in a still image – dead weight that the moving image dissimulates by carrying it along in its flow, like so many drifting skulls. Kuntzel’s form of slowness is presumably more due to the weak animation of an image which, while remaining identical to itself, trembles ever so slightly, with a semblance of life passing through it, and which only further dramatizes its inflexible rigidity. As though taken in the movement of its appearance or emergence, it only reveals itself at the cost of revealing itself to be definitively unalterable.

Pierrot indeed already played the third wheel in another Watteau painting, Pour garder l’honneur d’une belle [To protect a beauty’s honor], completed ten years earlier. There on the stage of a theatre, impassively watching the performance (in the middle of it), he calmly holds this same despairing position as that of Pierrot. The quatrain accompanying the engraved reproduction of this painting gives a clear indication of his function: “Pour garder l’honneur d’une belle / Veillez et la nuit et le jour, / Contre les pièges de l’Amour / C’est trop peu de Pierrot pour faire sentinelle” [To protect a beauty’s honor / Watch out night and day / For the traps set out by Cupid / It’s not enough for Pierrot to stand guard]. It thus seems that Gilles cannot ignore his Pierrot costume, however poorly fitting and baggy, in which he floats ridiculously. A hostage of his own role, he remains on watch after the show ends, perhaps because no signal or bell has sounded to indicate the end of the performance, halting the theatrical conventions and ending the pretense of acting. He remains silent, set loose via an unmediated transposition, as though he were bewilderedly relegated to a cloakroom (strangely, he is not even in makeup). Neither actor nor character, in short, he is only there as a representative of the performance. An unnecessary valet to the show, the understudy to his own effigy, he is the main attraction.

Kuntzel’s video adds a numbness to the immobility of the character of Pierrot, an absence to the self, which is no longer only an instant of distraction or momentary stupor, but a lasting prostration. His immobility, which was in response to the demands of the pose, here turns into apathy. What else might these resting actors represent – wearing the clothing of asylum patients and getting some air under the benevolent watch of a doctor, while carrying on their conversation from one picture to the next – other than his own internal monologue, overwhelming Pierrot? Aggrieved by a pronominal hook that leaves him arms dangling, he stands straight as a pole, installed in his own sluggishness. Or is it that he is nothing without the one he takes for Columbina, who has fled with Harlequin? In any case, he has clearly given up. Keeping vigil day and night, standing guard, the story can only play out behind his back, while he is diverted, in fact. “Pierrot doesn’t matter”, he is but the image of the spectator. No one will berate him for falling asleep.

Damien Guggenheim

Translation from French : Sara Heft

Thierry Kuntzel, “Sur Gilles et La Peau”, in Trafic, no. 64, winter 2007, p.50.

Giorgio Agamben, Polichinelle ou Divertissement pour les jeunes gens en quatre scènes, trans. Matin Rueff, Macula, 2017, p.92 [quote translated from the French].