On 27th March 1973, a Native American militant got up on the stage to refuse the Oscar for Best Actor which had been awarded to Marlon Brando for The Godfather, in protest against Hollywood’s depiction of Red Indians and the repression then taking place at Wounded Knee. She left the stage amid boos, which were above all aimed at the actor who had affronted the Academy in three ways: refusing an Oscar, not even showing up and giving a moral lesson1. It is one of the most famous speeches in the history of the Oscars, which for the first time had been turned into a political platform. In 2022, after the #Oscarssowhite campaign which led to the Afro-American scholar Jacqueline Stewart taking the helm of the Academy, Sacheen Littlefeather became a symbol and was honoured as she deserved. She gave an interview/testament lasting 3h402, then was received with great pomp by the Academy before passing on 2nd October from a long disease at the age of 75.

Except that, smash bang wallop, three weeks after her death, her two sisters “revealed” that Sacheen Littlefeather (born Marie Louise Cruz) was no Indian. Her father’s family was not Apache, or Yaqui, but Mexican from Mexico3. In the current mood, it is probable that research would have been carried out and that she would have been “cancelled” before any results had been obtained. But the press was paralysed by huge embarrassment. The Academy published a press release “recognizing self-identification” while adding a warning to her video-testament in which it declined any responsibility. This affair became even more complicated because it had been made public by Jacqueline Keeler, a tough, controversial figure who was conducting a witch hunt against Pretendians – Whites pretending to be Indians. One of her sisters, Rosalind Cruz, continued her crusade on Twitter in a distinctly conspiracy-theory tone, but she at least hit the bull’s-eye when she proclaimed: “if you don’t believe us, do your own research”. Only one person bravely defended Sacheen Littlefeather4, but without covering certain grey areas. To sum up, this business is a typical case of media invisibilisation.

When viewed from France (where none of this was reported, not because of a decision but out of ignorance), Americans’ unhealthy obsession with origins always seems extremely odd. But, above all, this all misses completely what is original about the story. There are two camps: those who want to strip one of the queens of the Indian cause of her crown and who desire “reparation” for the harm she did – but we may well wonder who she harmed, or else whose place she is supposed to have usurped, given that no one could have done what she did; and those who defend Sacheen Littlefeather against the accusation that she lied and committed ethnic fraud. This is an exemplary case of the characteristic binarity which grips the United States, enmeshed in its obsession with identity. You feel like saying to this nation: have you lost your sense of humour? Or your capacity for fiction? Or your taste for the extraordinary? What about your larger-than-life characters, your self-made men and women, all those people who invent lives for themselves? As the years go by, the United States seems duller, more cramped, more awful. With Sacheen Littlefeather, we have an example of an extraordinary personality, someone who, whatever their origins, invents for themselves a fictional character. A genuine heroine.

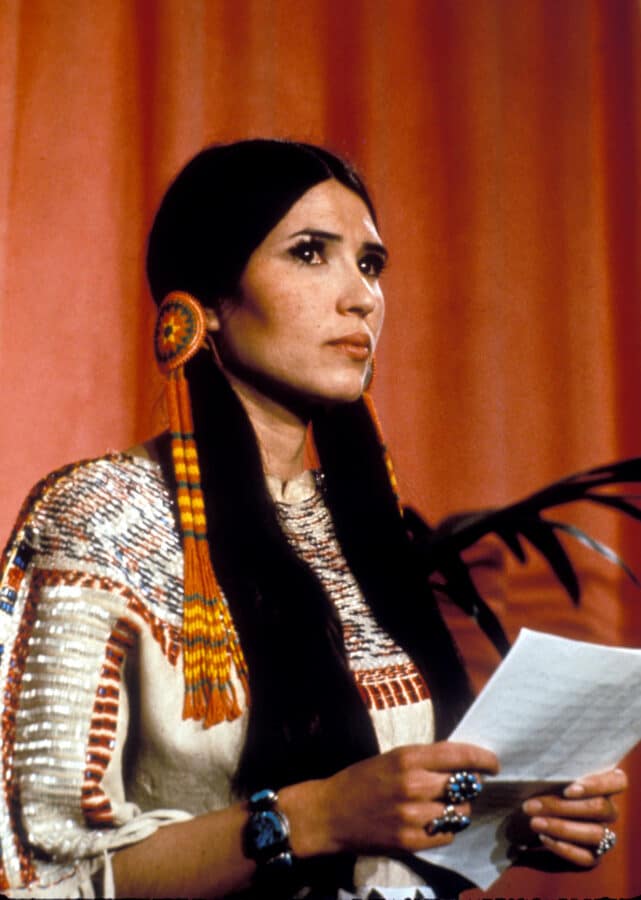

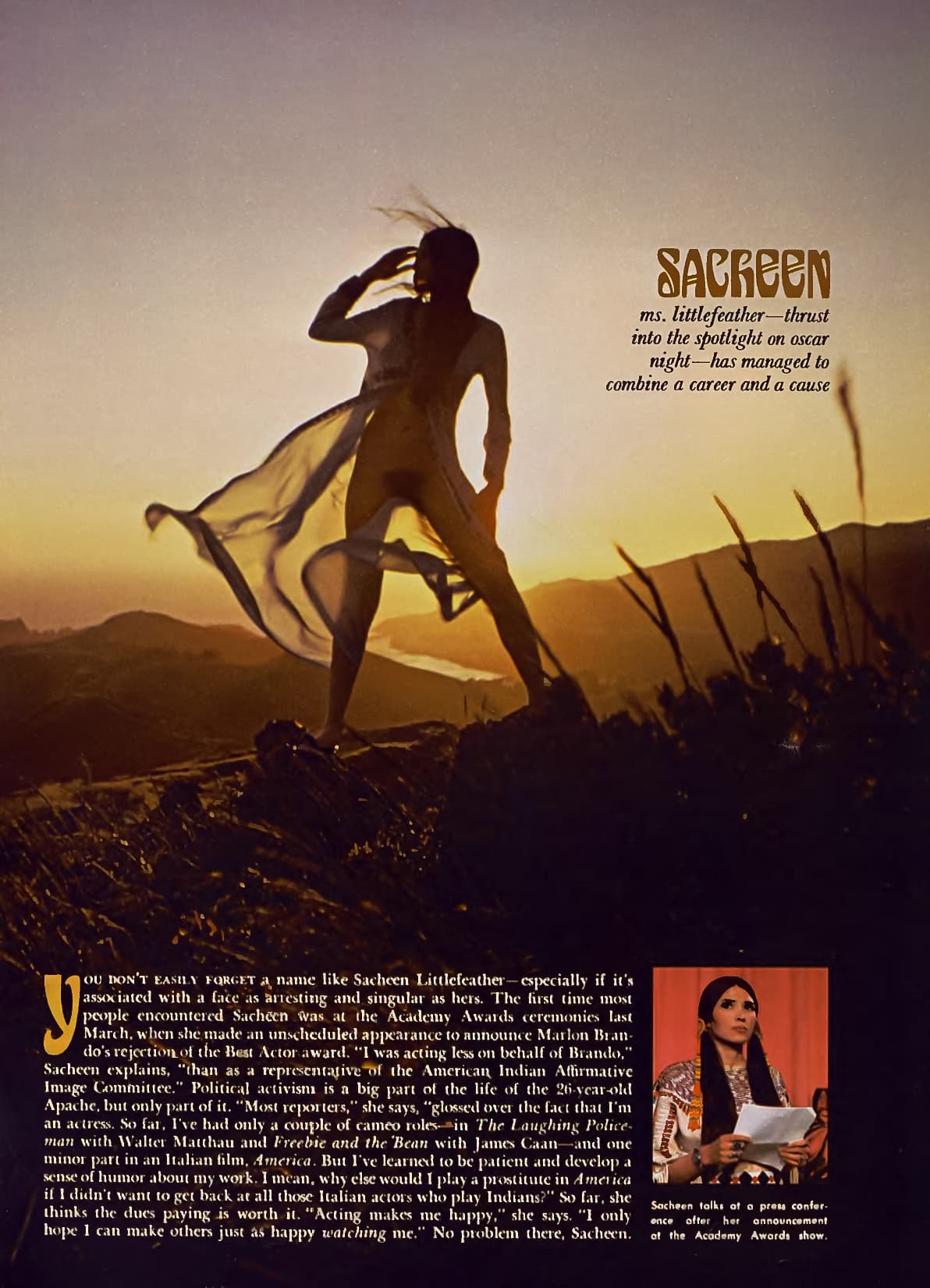

Sacheen Little Feather in Playboy, October 1973.

Photoshoot for KronTV, January 1971.

Here come a few glimpses of this ungraspable life. She was born in California of a white mother and a father of Mexican extraction. At the age of 19, she heard voices, attempted suicide and was interned in a psychiatric hospital for a year – a terrible ordeal which she never sought to conceal. She was diagnosed as being schizophrenic. On her release, she was helped out by an Indigenous association and in turn joined a committee militating for a just depiction of “Indians” on the screen. In 1969, she started going by the name “Sacheen Littlefeather”. As an upcoming actress in San Francisco, she met FF Coppola (who had made San Francisco his base) before entering into contact with Brando, an ardent defender of the Indian cause. She also claimed that she had taken part in the occupation of Alcatraz, but what is sure is that she was elected Miss Vampire USA in a beauty contest, under the name “Sacheen Littlefeather of Alcatraz”. She posed both nude and dressed (up?) as an Indian, for Playboy in 1972, a photo shoot which would be published only in October 1973, after the Oscars. She played a minor role as a flirtatious prostitute, during which she chewed gum while wearing outrageous make-up, in a pale copy of The Godfather shot in San Francisco (Il consigliori by Alberto de Martino). Then came a transfiguration: we look on amazed, is this the same woman? She got up on the stage at the Oscars with an extraordinary intensity, an imperial calmness and a disarming gentleness. She was given just one minute and was prevented from reading Brando’s text, so she improvised with a miraculous power of conviction. Brando put her on stage, but she stole the show.

After that came countless improbable tales. Six security man were needed to stop John Wayne from chucking her off the stage. This sounds too good to be true: was the Duke intent on replaying The Searchers5? She claimed that Hoover told the FBI to follow her, but he died in 1972 and she was no Jean Seberg. She and Russell Means asserted that her performance at the Oscars had been decisive for the protestors at Wounded Knee, who watched it live – although it turns out that he was not there that day and the electricity in the camp had been cut off.

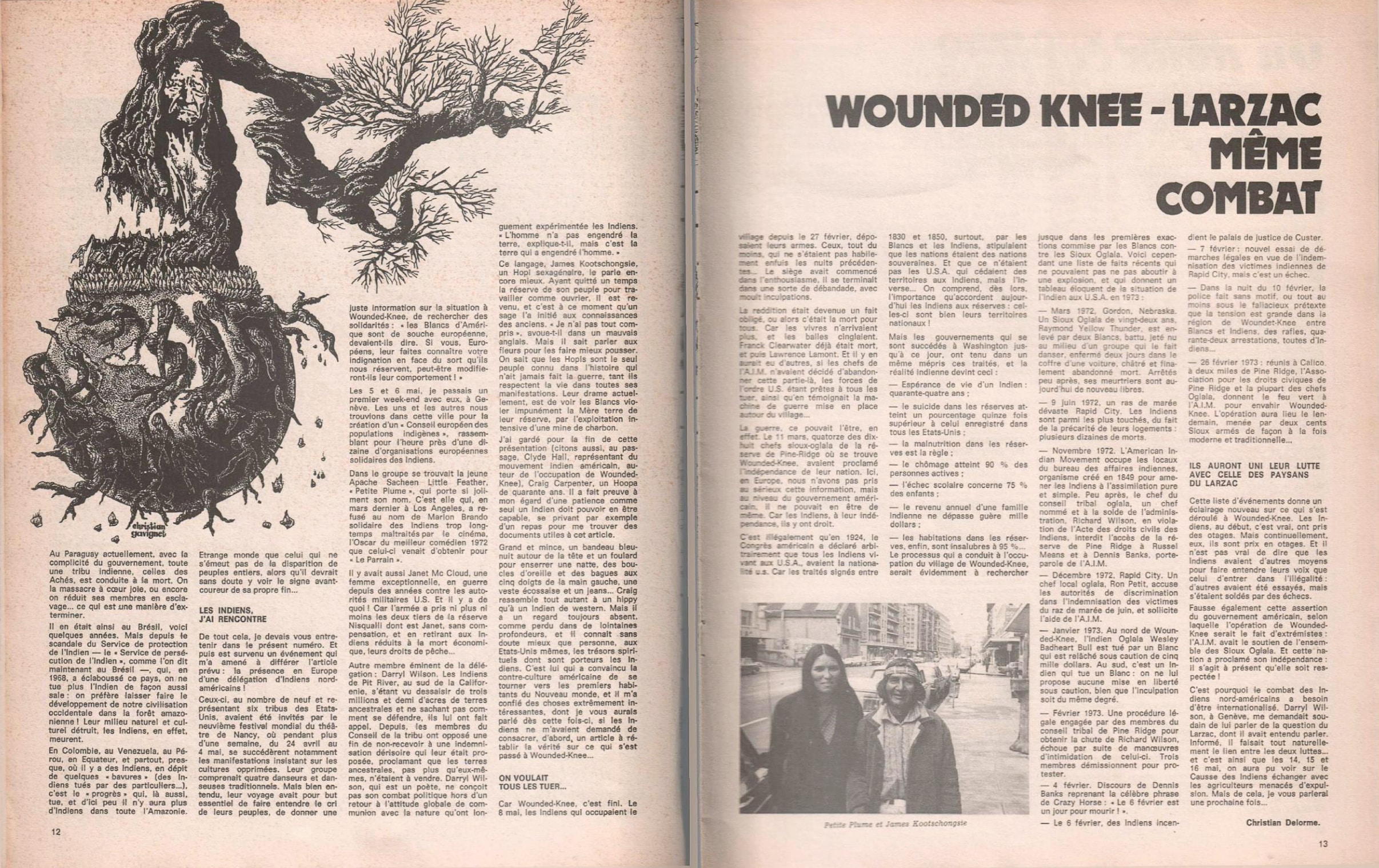

“Wounded Knee-Larzac, même combat”, excerpt from the newspaper "La Gueule ouverte", June 1973.

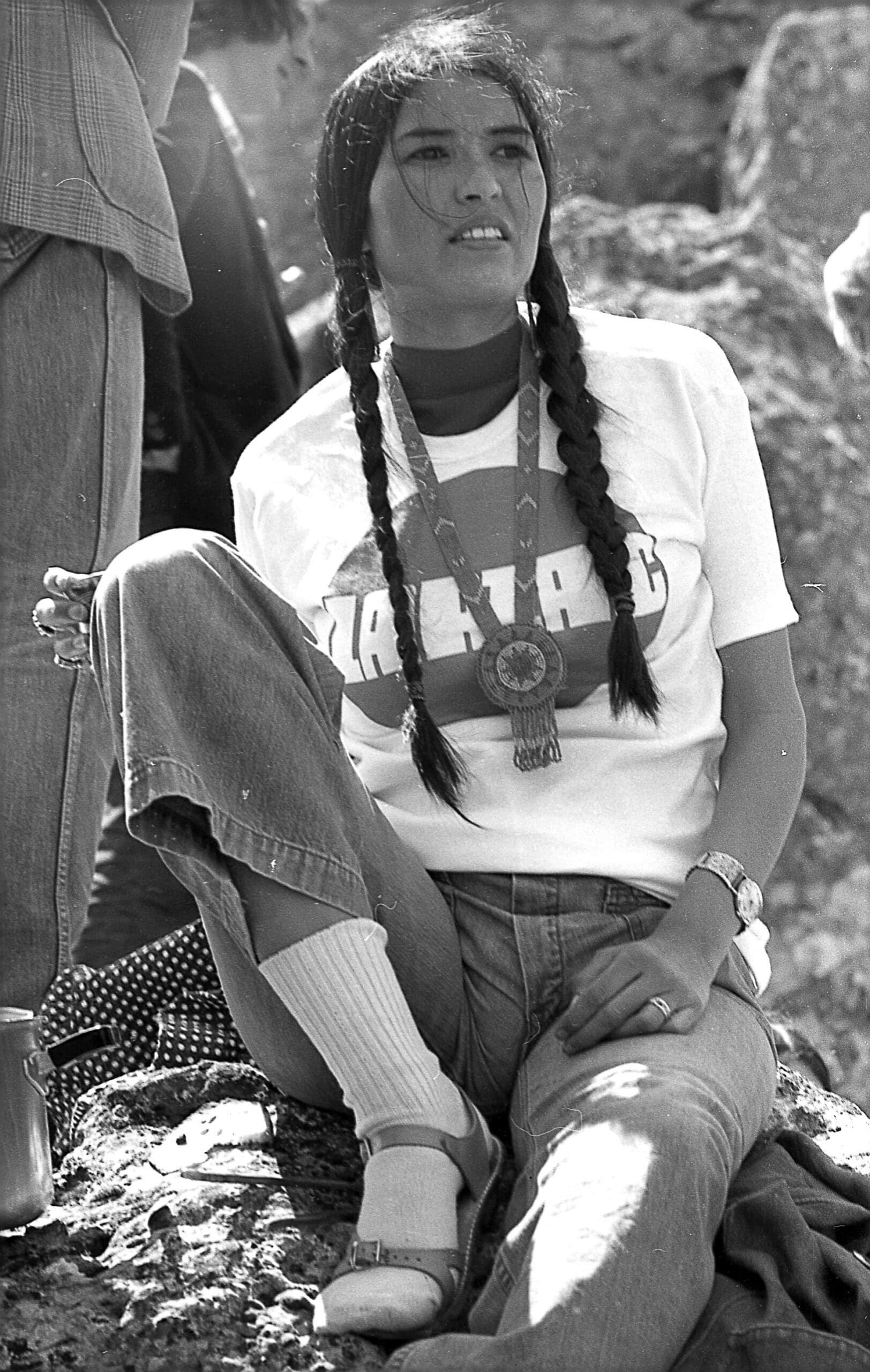

Sacheen Littlefeather in Larzac, France, 1973.

Photography Michel Langrognet.

Come as what may, but many actions do bear witness to her commitment. To take just one example, the American press skated over her trip to Europe, but an article in the militant green paper La Gueule ouverte (n°8, June 1973), founded by the Charlie Hebdo team, “Wounded Knee-Larzac, même combat”, reported that a delegation of nine Native Americans from six nations had been invited to the theatre festival in Nancy in homage to oppressed peoples (24th April-4th May). This delegation then went to Geneva for the setting-up of a European Council of Indigenous Nations, then to Larzac from 14th to 16th May6. All the reports speak of the commitment of this woman nicknamed “Petite plume”7. So, one month after the Oscars, she was no longer just trying to be famous. She had turned Larzac into Apache turf.

She then appeared in four Westerns. This also led to total confusion. How could she agree, in 1974, to play exactly the same kind of roles of raped, slaughtered squaws which she had decried in front of the Academy, in two such salacious films as Johnny Firecloud and Winterhawk? But, at the same time, she also played an attorney in The Trial of Billy Jack (Tom Laughlin), a z-movie but a big hit at the time, in which she took the floor to defend the cause, just as she had done in front of the movie professionals. She appeared only to be killed in Shoot the Sun Down, but her big moment with Christopher Walken had been edited out when this film, shot in 1976, came out two years later. She was not behaving like an icon, but as an actress, going from one part to the next, in both her life and in films, and her finest role was always that of a spokeswoman. When asked about her nude photographs in Playboy, she replied: “Everyone says Black is beautiful, why not Red?” The saddest thing is that she was side-lined from TV shows, even though she had an irresistible eloquence, as can be seen in a local San Francisco programme in 19768. She had just undergone a serious lung operation and announced that she was devoting her life to physiotherapy. Until the end of her days, she took part in numerous militant actions in the Bay Area.

What do these exaggerations and contradictions prove? Firstly, that what counts is the legend: we’re in Hollywood after all! So, it’s sad to see seriousness take over: the Academy now sees itself as an institution, with both a duty and a mission, but good luck to it if it intends to administer a place which plays constantly with masks. Hollywood is a centre of entertainment, and any attempt to regulate, control or identify it is doomed to failure or derision. Iron Eyes Cody is an emblematic instance of this. Supposedly Indian, it turned out after 60 films that he was out and out Sicilian. This makes us Europeans laugh and would not have outraged Americans that much fifteen years ago. In 2009, the documentary Reel Injun, devoted to the depiction of Native Americans (which Sacheen Littlefeather worked on) tells the tale of Iron Eyes Cody but the (Indigenous) filmmaker was tempted neither to discredit nor cancel him. What has happened since, to turn this into a taboo?

On stage at the Oscars, Sacheen Littlefeather denounced degrading depictions which she at once countered, as if in a happening or a performance, by projecting a glorious image of the Red Indian Woman. She might have otherwise just been able to find minor roles, but here she landed a magnificent one (with Brando, as the visionary director), but she also staged herself (Brando was watching her on TV). She would become the Red Indian Woman. The one that was missing. The one that wasn’t seen on the screen. She would embody Indian Pride. A few years later, John Wayne said: “If Brando had something to say, he should have appeared that night and stated his views instead of taking a little unknown girl and dressing her up as an Indian”. Was it an actress’s costume or dress for a powwow? But isn’t that the very same get-up? Some wanted her to be enrolled in a First Nation (enrolled meaning officially belonging to a tribe), but she was enrolled only in the cinema and in life. The words ‘actress’ and ‘activist’ have the same root. She enrolled herself as a roving actress and spokeswoman. And she believed in it, she wasn’t fooling anyone.

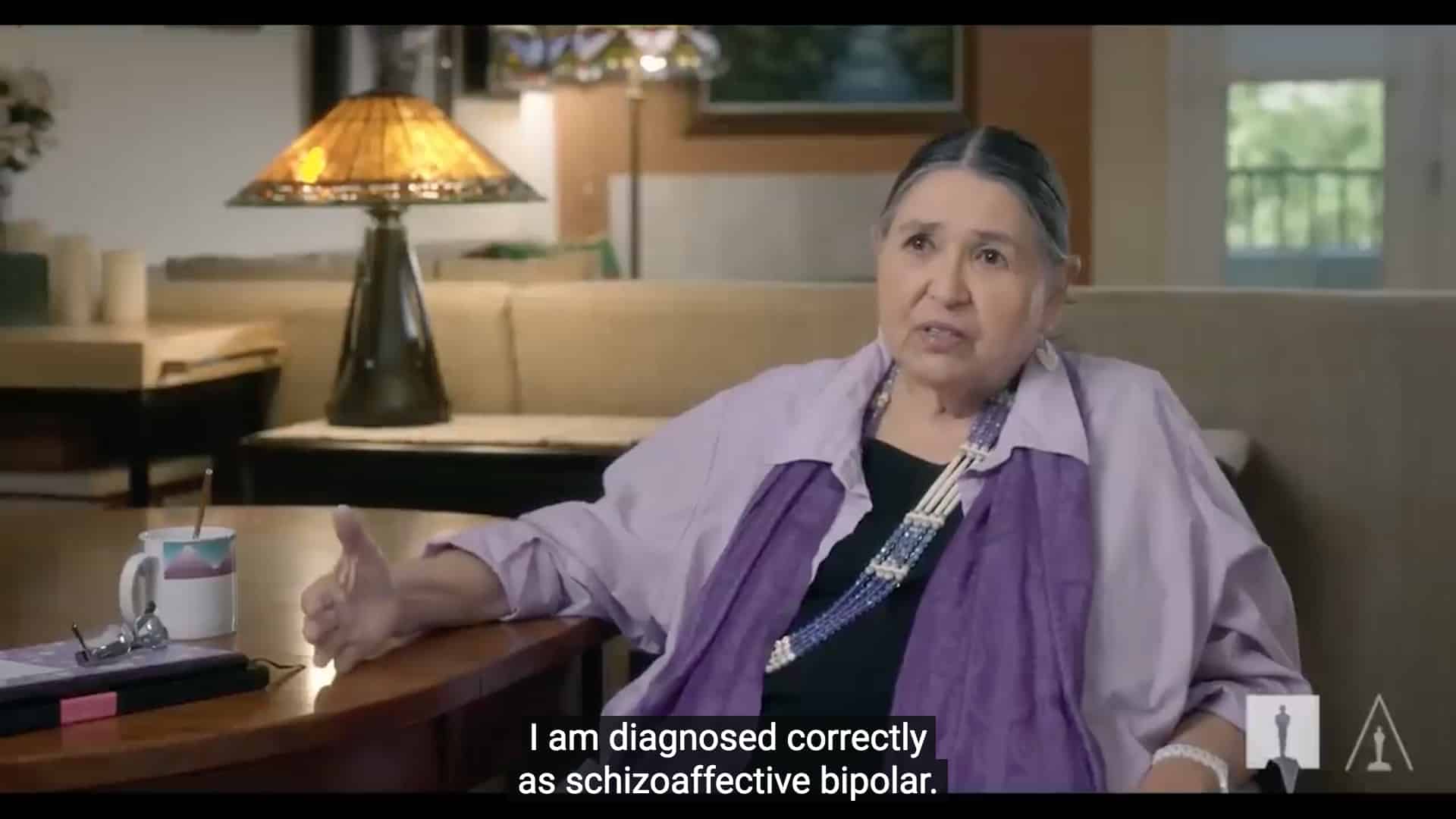

And then there is the psychiatric angle. In a wide-ranging interview with Jacqueline Stewart, Sacheen Littlefeather said that she had been correctly diagnosed as a schizophrenic and that she had been looking after herself ever since. She went into great detail about her illness. She highlighted her “never satisfied need for recognition”. Here, too, we can admire her aplomb, her taste for narrative, her increasingly off-putting ease (quite suddenly she took up singing). There is a feeling that she was writing fiction live. She abruptly told the Afro-American Jacqueline Stewart that the doctors around her had been hooded like the KKK – which is at the very least a daring comparison. This stay in a hospital has also become suspect. She compared it to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) in which “Chief,” the first leading role played by a Native American in Hollywood, escapes from an institution. She seemed to seize on whatever came to hand. So, who do we have in front of us? What was her life like? Is this the courage of someone who had slain her demons and been “born again” as a “Red Indian”? That would be admirable. A schizophrenic has found some way to stay alive… But we can have no idea about all that, because Sacheen’s mystery is a crystallisation of fiction. The most awful sign of this can be found in a little-known video from 1997, in which she claims to have been abandoned and brought up by a white foster family, before finding again her blood-brother (who never existed)9. Was this compulsive lying or a psychotic episode?

Everyone wonders if she “was or wasn’t her”. But, what’s the difference? This is what Americans fail to understand in their modern identity crisis. Whether she was or wasn’t a “Red Indian”, her life – her action – remains exactly the same. She did not have an Indigenous childhood, or was enrolled in a tribe, and when Jacqueline Stewart asked her what her supposedly Apache father had handed down to her, she answered evasively: “not much”. We can see that this is a very tight rope. So, if we want to play this rather tedious identity game, it might be argued that, whether she was of Indigenous extraction or not, she had in any case had a moment of awareness, leading to a decision to take on an Indigenous identity. In what way is this identification, when she made up her mind, as a Mexican, to act like an Indian, less arbitrary than it would be for a born again Christian? The fact is that, at a given time in her life, she adopted an Indigenous identity – whether she could claim one or not, or whether she did or didn’t believe in it. No one knows, nor ever will, what she believed when she started to think of herself as a Native American in 1969. No doubt, she had good reasons to believe this – or want to. She may have latched onto the vague idea that she was of Indigenous extraction, and this turned out to be enough for a young woman in the making and in pain. She may have believed it sincerely, or played on family tales. She might have made use of it to escape from her illness. Or else her schizophrenia might have deceived her. She might also have lied. Never mind. What matters is that this disturbed soul found a way to reconstruct herself and stay alive. All the reports emphasise her unfailing sense of humour, and it is true that, over the pictures of her, there hovers a sphinx-like smile.

Stéphane Delorme

Translated by Ian Monk

1 « Marlon Brando’s Best Actor Oscar win for The Godfather | Sacheen Littlefeather », youtube, 2 October 2008.

2 Sacheen Littlefeatther interviewed by Jacqueline Stewart, youtube, 18 June 2022

3 Jacqueline Keeler, Sacheen Littlefeather was a Native American icon. Her sisters say she was an ethnic fraud, San Francisco Chronicle, October 2022.

4 Daniel Voshart, The Crashing of Sacheen’s Funeral, Medium, 4 December 2022.

5 John Wayne and the Six Security Men, Self, Self-Styled Siren, 19 August 2022

6 Christian Delorme, Wounded-Knee – Larzac même combat, La Gueule ouverte, 8 June 1973, p 1. [Read online (archive)]

7 Édouard Launet, Le larzac, de natifs en néos, Libération, 8 August 2003 [Read online (archive)]

8 “Sacheen Littlefeather Interview 1976 », youtube, 27 February 2022.

9 « Sacheen Littlefeather Modeling For Photo Shoot », film 16mm, 1’33”, Bay Area Television Archive, 16 January 1971. [Online Archive]