In my quest for artists and thinkers who attempt to escape anthropocentrism I came across F/EEL, a complex interspecies design installation by Sheng-Wen Lo and Yi-Fei Chen that homages the everyday traumas of one of the most mysterious and slippery fishes of the ecosystem: eels. I have asked the duo to reveal some behind-the-scenes and after-thoughts on their outlandish and compelling project. Federica Chiocchetti

Dear Reader,

Have a guess: which of the following statements about eels is false?

1. Eels can live as long as or even longer than humans.

2. In terms of price per unit weight, the market value of smuggled baby eels can rival gold at the end of the supply chain.

3. Modern “fish friendly” hydroelectric stations are equipped with turbines that allow 99% of eels and other migratory fish to pass through.

Let’s unveil the answer together with this letter. But firstly, what flashes through your mind when you hear the word “eel”? Is it a dish from grandma in your childhood memory that made you hesitate before digging in? Is it a snake-like, slippery figure wiggling through mud near a river? Or perhaps you, like us, have eaten a fair share of kabayaki eels, but have never seen a live one in your life. When the Embassy of the North Sea, a Dutch organization focusing on environmental agendas surrounding the North Sea, commissioned us to produce a participatory project focusing on the troubled lives of European eels, we felt simultaneously felt distance and familiarity with our subject. Nevertheless, we were immediately intrigued by this mysterious fish, which can live up to 80 years.

Obscured and Challenged – Anguilla anguilla

Before the project, we did not know that there are European eels (Anguilla anguilla) swimming in rivers and canals in the Netherlands, as they are also present in major rivers in France, such as the Rhône, the Gironde, the Loire and the Seine. Actually, we knew nothing about what was going on beneath the water surfaces. For us, information on eels and the misfortune they endure came almost exclusively from books and online articles. In addition to the 6,000-kilometer migration route between Europe and the Sargasso Sea, it is an endangered fish constantly under anthropogenic pressure. Artificial hindrances for eels include hydraulic barriers such as dams and pumping stations, contaminated water bodies, invasive parasites, overfishing and illegal trafficking.

Direct Experience – Sensory-based Escape Room

A great challenge for us was how to establish a connection, or kinship, between eels and humans. Humans rely strongly on vision to formulate bonds with non-humans, which is why there are plenty of films and documentaries attempting to provide visual renderings of nature. However, eels are hardly accessible to our cameras; in fact, no scientist or underwater camera has ever seen European eels mate in the wild. What possible strategies do we have to spotlight a species that we cannot see?

A few years ago, in an exhibition at Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, there was a temporary blackout in one of the passages, making it completely dark. Walking along the dark passage, not knowing how long it was or what lay ahead, was an experience of insecurity. Incidentally, the dark passage became the most memorable part of the exhibition. We soon realized that, for this project, we would have to resort to direct experience.

We started off with numerous ideas, including making an obstacle course or designing costumes that might make a person act like an eel. But when the idea of an escape room emerged, it didn’t take long to realize that this form could capture the situation elegantly. As most humans live in environments designed by and for humans, it is seldom possible to have a different sort of experience. These environments, to the contrary, often work against other creatures and plants, producing hurdles in their daily lives. We imagined a space not designed for humans, with a series of interactive contraptions corresponding to eels’ unfortunate encounters.

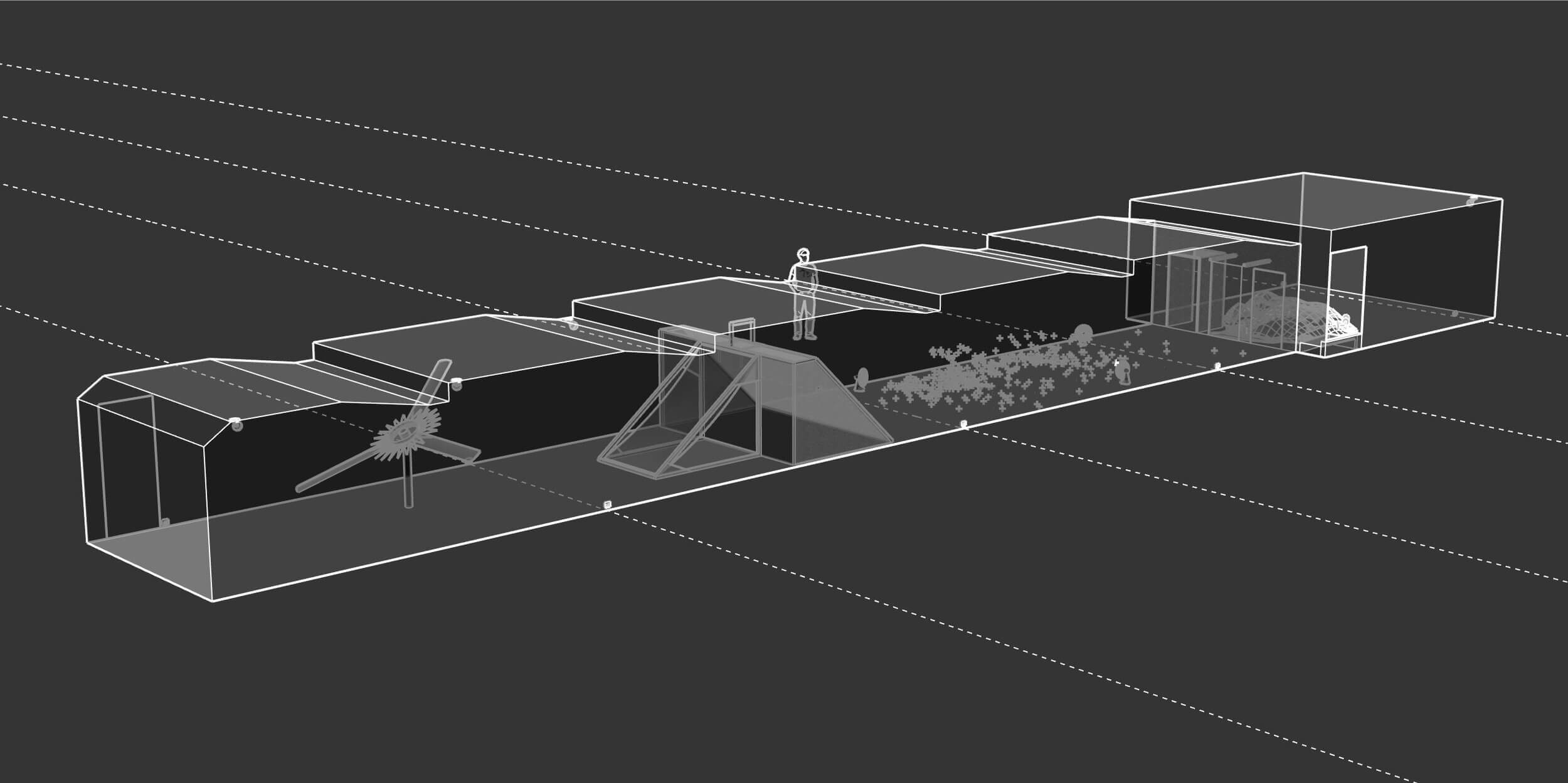

Participants enter the space alone, and temporarily cross a thirty-meter-long passage that was built counter to their physiology. The goal is to find the chamber’s only exit and escape from it. Unlike traditional escape rooms, there are neither verbal nor logical clues, so participants rely on instinct and senses, which are either distorted, deprived or sharpened.

F/EEL: A Space Not Designed for Humans

You might wonder whether this escape room, F/EEL, is an entertaining game for humans. While escape rooms are indeed a form of game, we believe that there is nothing entertaining about an eel’s troubled life, in fact. To balance the tonality of the project, we made it intense yet secure; with numerous illusions of threat and instability, F/EEL treads the thin line between safety and danger, invoking fear, stress, anxiety and frustration. To retain the element of surprise, we made sure no part of the design was leaked over the course of the operation. The project was installed at a former military shooting range at Marrineterrein Amsterdam, surrounded by waterways where eels and other migratory fish pass. As in real life, the space imposed both barriers and aids to participants.

Barriers

Eels begin their life cycle in the ocean and spend most of their lives in fresh inland water, or brackish coastal water, returning to the ocean to spawn and then die. When they arrive in countries such as the Netherlands, they can be easily blocked by more than 10,000 well-engineered dams, locks and pumping stations equipped with lethal turbines. Water contaminants including PCB are also crucial damaging factors, which not only cause physical harm, but dull their senses.

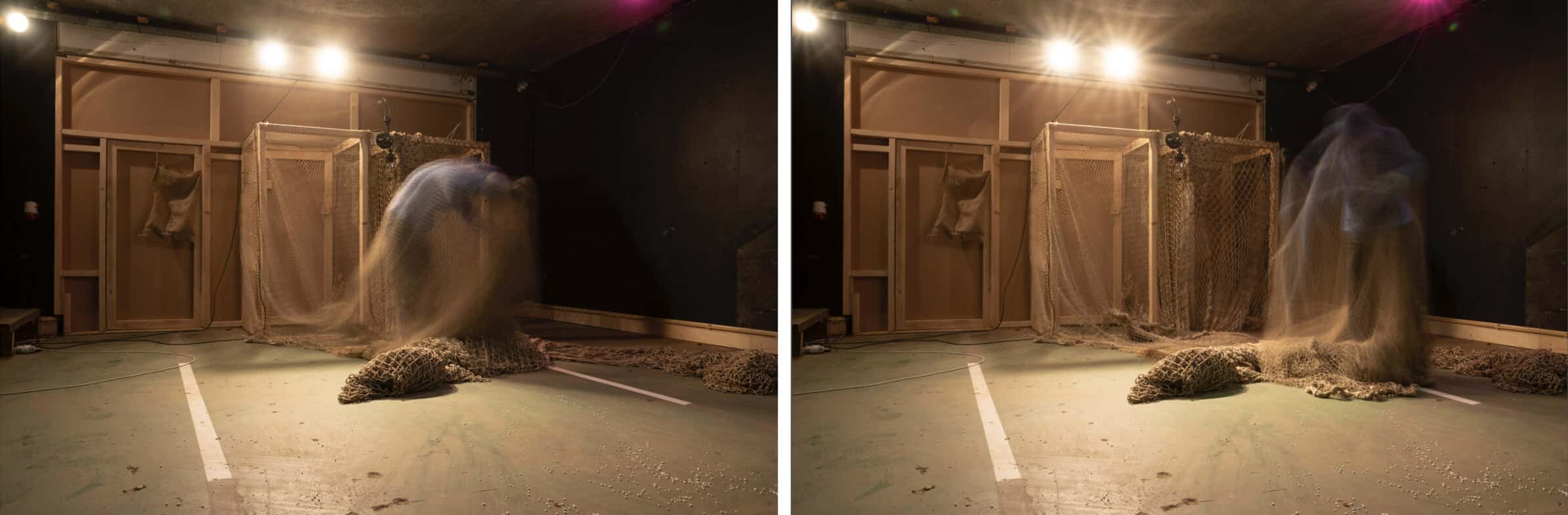

Eels have subpar eyesight, and they navigate with other senses such as smell, hearing and pressure, often subject to interference due to pollution. We attempt to handicap participants’ senses by making several segments of F/EEL dark and noisy, confronting them with various obstacles, including a rotating turbine, a dam, a debris field filled with marine waste and a trap made by proper fishing nets.

We would like to highlight the trap here. Eels cannot be farmed in full cycle in artificial environments, so every eel in an eel farm originates from the ocean. It is estimated that as many as one-third of the eels reaching Europe are smuggled to Asia, due to culinary demand and higher market price. Poaching has been a real threat for wild eel populations. The value of a glass eel, sometimes called “white gold” for the astronomical prices it can command, increases exponentially as it moves along the supply chain. A European fisherman may get ten euro cents for a glass eel, but when it is farmed into a fully grown eel in Asia, its price can increase one hundred fold. In other words, the profit for trafficking glass eels exceeds guns, drugs and humans. In our trap system, there is a scenario from which participants cannot escape. Being trapped, or not, depends solely on luck — just like eels’ real life, it has nothing to do with intelligence or physical strength; sometimes you are just unlucky enough to be at the wrong place, at the wrong time.

Aid

Numerous endeavors have been made in an attempt to provide assistance to eels and other migratory species, but not all of them are effective. Some contemporary hydroelectric dams and pumping stations are equipped with fish friendly turbines, but mortality rates may still be as high as ten percent. For barriers such as weirs, locks and dams, eel ladders are sometimes implemented to allow possible passage. These human-designed ladders are watered ascending ramps that provide the eels a climbing substrate to “push against” while slithering upstream. In reality, however, not all eels are guaranteed to swim through, as they differ in age, size and stamina.

In designing F/EEL, we also wished to assist participants with ladders to overcome the barriers. We imagined ourselves as aliens trying to build ladders for humans — thus the question of interspecies design can be asked: how do aliens know for sure that humans will understand how to use these ladders? From our alien perspective, we only know that humans usually use their feet alternately to move forward on many surface types. With this in mind, we constructed two ladders for them to overcome a high wall: a steel ladder with automatic-locking foot pedals that carry a person upwards; and a fabric ramp.

What We Witnessed

In the chilly autumn of 2020, more than 120 participants tried to escape from F/EEL; the success rate was less than 30%. We moderated the sessions onsite, monitoring their safety conditions through infrared security cameras. Everyone confronted the space differently, and came up with strategies according to their age, size and stamina. We were hoping that the participants would utilize their bodies and senses rather than their cerebral qualities, but we realized that lots of people tried to “outsmart” F/EEL. We optimized the space over several days of trial sessions to reduce these possibilities. As a result, lots of participants were forced to engage in survival mode, and experienced frustration, fear and anger with occasional screaming, swearing and destroying random things with brute force in the process. Many gave up in the heavy fishing nets, not because they were truly stuck or trapped, but due to exhausted mental strength and depleted confidence. Interestingly, children outperformed most adults, at least in the parts that require less physical power.

Not everyone knew how to use the ladders — some got the hang of them in first attempt, some taller men tried jumping through the barriers, some kids climbed between the vertical bars of the steel ladder, some tried to charge the fabric ladder in high speed but slipped, some gazed at the ladders for twenty minutes, and ultimately gave up.

Some participants stared at the moderators when they got stuck, expecting to get help. However, the moderators cannot provide any assistance until the session time has fully elapsed. There was one session in which a young boy was frightened and called out for his mother repeatedly. We, as moderators, hesitated when deciding whether we should allow the mother to encourage him vocally. Of course, we felt sympathy for the intimidated child, but in reality, baby eels have no parents to support and protect them, even in the most brutal environments. What would you do if you were the moderator of F/EEL?

Despite the stressful behavior inside F/EEL, most participants expressed joy and relief when they escaped or were rescued, as they did not expect the high intensity of the project, and that of the lives of eels. After all, F/EEL was a toned-down imagining of what it is like to be this mysterious fish; for the eels, it is not a game, but everyday life, with much deadlier stakes.

— — —

You might wonder what is the point of all this, since no one can really translate an eel’s experience in human terms. Indeed, F/EEL is not a scientific project, but we hope it can access something within us that science and logic cannot — a part of us willing to form kinship with a fish that we may have never seen.

The cognitive gap between humans and non-humans may be open forever, regardless of how science or civilization have evolved. For us, F/EEL was not about closing this gap, but asking what we should do with it. As humans, people are free to envision bright designs and scenarios for non-humans, but what is often forgotten is that no one can avoid doing so anthropocentrically; and what humans envision may not actually be so bright for the species in question. Perhaps the only thing we can do is to keep humbly asking what they really need, and disperse these questions beyond our practices.

As fellow beings in the universe, and co-occupants of time and space, we wish you a delightful passage.

Warmest,

Sheng-Wen Lo & Yi-Fei Chen