The image-milieu: re-examining objectivity and the centre, by taking the point of view of the in between

With the discovery of mesology (the science of milieus), a new theoretical and practical context of the image opened up to me. From the perspective of an anthropocentric re-examination, the notion of ”milieu” conveyed today by Augustin Berque34, as well as Bernard Stiegler35, emerges as an essential theoretical tool to rethink and heal the relationship that we have with the world, by going beyond the premises of objectivity and universality implied by the terms “environment” or “ecology”.

This notion is in effect differentiated from the environment (Umgebung) by Jacob Von Uexküll,36 who proposes the term Umwelt to designate the perceptual world which is proper to each living being. Every species (and even every individual) experiences the world according to their own subjectivity, their own self-centred world. As Victor Petit explains it, this notion of “centre” has thereafter been redefined as an “in between”37. Indeed, whilst the milieu defines itself as the specific mode of perception/action that the organism establishes with the world, it appears impossible to think of it as totally intrinsic or extrinsic. It must be considered as an intermediary space, as a “mediance”38, as a mi-lieu (mid-place). The individual/milieu complementarity (Canguilhem) 39, the space of the body as mediator (Merleau-Ponty)40 render this mi-lieu a constitutive relationship. Simondon thus speaks of an “associated milieu” to specify that the individual is not “in relation with other subjects or with itself or other realities; it is the being of the relation and not in relation, relation being an intense operation, an active centre”41.

The Écoumène (Ecumene) project rethinks the supposedly “objective” experience of photography through the prism of the subjective and relational experience of the inhabited milieu. As Estelle Zhong Mengual notes, “to be a point of view is to be something else than the environment of others: in this respect, one could argue that being a point of view is, on the contrary, to inhabit”42.

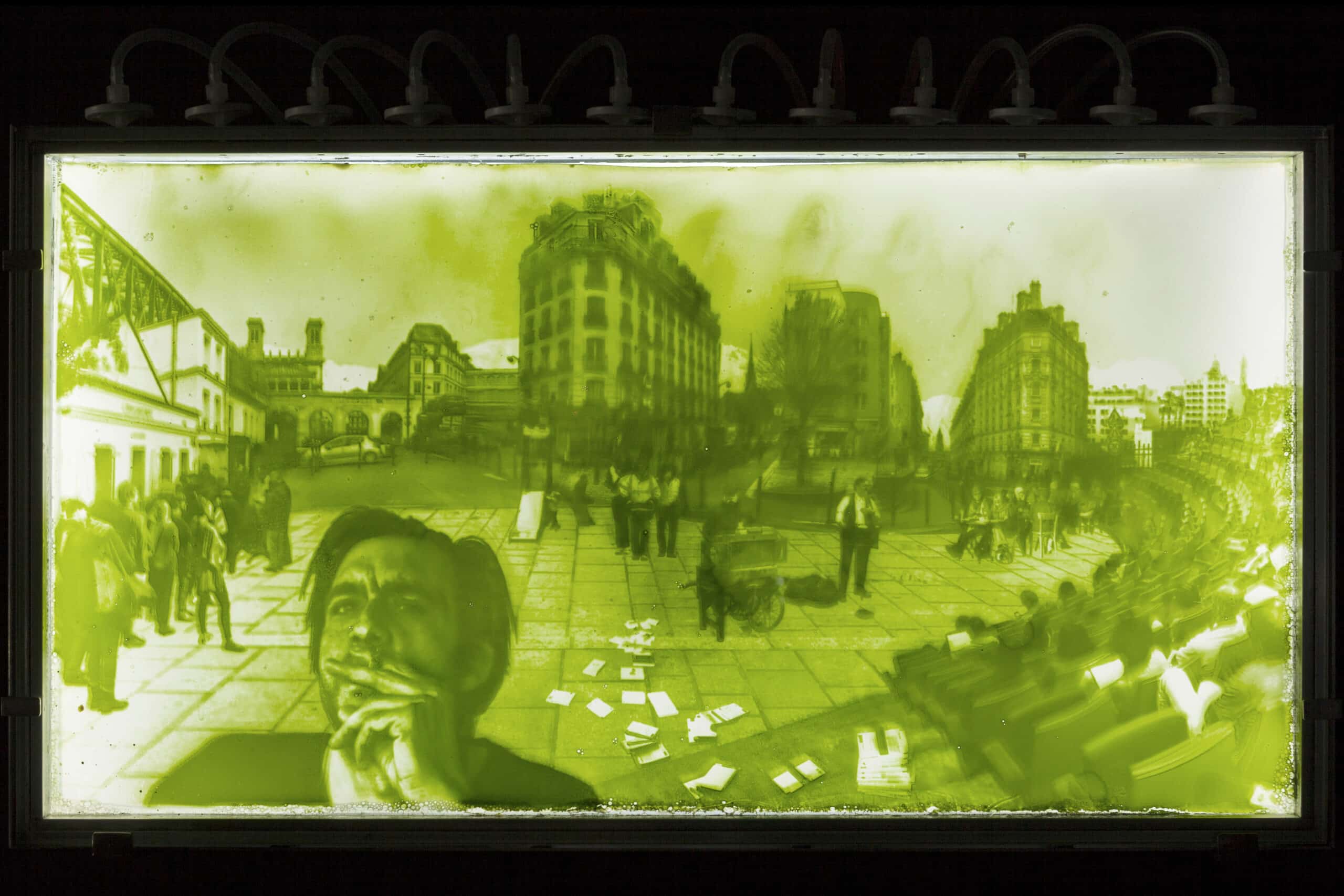

In the first edition of this series (Écoumène V.1 : Victor Petit), the philosopher and mesologist sought to represent his own milieu by elaborating on his own unique relationship with the neighbourhood of Ménilmontant in Paris, where he grew up. The composition frees itself from the spatial and temporal realities of the neighbourhood, to put into imagery the relational space that defines this mi-lieu according to Victor. The landscape-portrait is thus created by linking emblematic locations and snapshots of life that convey the spirit of the place, its memory, its history, rather than its geographic reality. However, the algaegraphs document an intermediary space which does not altogether embody Victor’s vision: Unable to access his thoughts and the specific image that he has of this place, the representation that I offer appears as a kind of subjective world objectified by photographic fragments collected and reassembled from his story. As in any experience of landscape, the algaegraphic representation is therefore neither entirely objective, not entirely subjective, but instead, offers itself as a “trajection” (Augustin Berque): the theoretical centres of the subject and the object are correlated by the reciprocal interactions (here, the text and the discussions with the protagonist) to produce a concrete reality (the image), which is “trajective”.

The interwoven image: the image-milieu considered as a new relational and pluralistic space

The mesologists nevertheless differentiate beings in the world of lower animal forms and the higher animal forms, which the human being belongs to, because for them to have an “awareness of a world as the common reason for all settings and the theatre of all patterns of behaviour, then between himself and what elicits his action a distance must be set”43. The reasoning animals live with or are subjected to this incessant dilemma of the milieu, which both absorbs them in the world and keeps them at a distance. For Canguilhem, this “detachment of man from the world”44 defines the space of thought. For Victor Petit, it is language that allows the human being to slip into this mi-lieu and to claim their place in this space of mediation. For me, image can be considered as a medium-milieu, as a form of language for the eyes. Like many others, Raymond Ruyer explains this particular mode of mediation by the appearance of the “symbolic function”. In the gradual exteriorisation of the organs towards the instrument, a type of duplicate of the exterior world appears. The mediation of the neural system re-establishes the continuity between the organ and the instrument, between the forms perceived and their meaning (symbol-signs). This second world (Welt) of the human being remains nevertheless fully assimilated to its biological being (Umwelt)45.

This is without doubt what allows Augustin Berque to define our experience of the human milieu (ecumene), as “the ecological, technical and symbolic relationship of humanity to the terrestrial expanse”. This relational interweaving which enables the different aspects of our human experience to be bound together in one experience of the coherent world appears to be equally essential for Bernard Stiegler. For him, the rupture of this “organological” system of mediation — which connects the psychic and biological organs to the technical organs, by enabling social organisations to emerge — leads to discontinuities in the perceptive-active experience of the milieu through which the individual elaborates themselves on an individual and social level. This “dis-sociated milieu” according to him, results in, “symbolic misery” no longer enabling the mechanical to be linked to our individual biological experience, and by extension would jeopardise the creation of shareable spaces between human beings — and I would add non-human beings as well.

Note #5 – Écoumènes (Ecumenes), 2018-2020.

The “Écoumène (Ecumene)” series, initiated in 2018 is derived from the Algaegraphic process. Here, the project echoes the notion of “ecumene”, which for geographers designates the totality of terrestrial spaces inhabited by humans. For Augustin Berque, the ecumene is more precisely the “simultaneously ecological, technical and symbolical relationship ” that the individual has with their milieu. This series thus explores, in the form of individual or collective portraits, the multiples ways to inhabit a land. Following a field survey, documented by means of photography, a subjective composition of this land is produced in the form of a negative which will then be interpreted by the microalgae. Each version of this series involves other disciplines that shed light on the site’s story.

Note #5 – Fig. 12 Ecoumène V.1 : Victor Petit, 2018. View of the work in the exhibition « La fabrique du Vivant » (“Designing the Living”), Centre Pompidou © Lia Giraud

Le premier écoumène, Écoumène V.1 : Victor Petit (2019), a été réalisé pour l’exposition « La fabrique du vivant » au Centre Georges Pompidou. Il évoque la gentrification parisienne et la disparition inéluctable du Paris populaire. Le philosophe Victor Petit interroge ces transformations dans un court texte accompagnant l’Algægraphie.Crédits

Écoumène V.1 : Victor Petit

Réalisation artistique : Lia Giraud

Collaboration scientifique : Claude Yéprémian

Texte : Victor Petit

Traduction : Igor Galligo

Production : Centre Pompidou, Équipe «Cyanobactéries, Cyanotoxines et Environnement» (UMR 7245 CNRS, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle), Centre de Ressources et Recherche Technologiques (C2RT, Institut Pasteur).

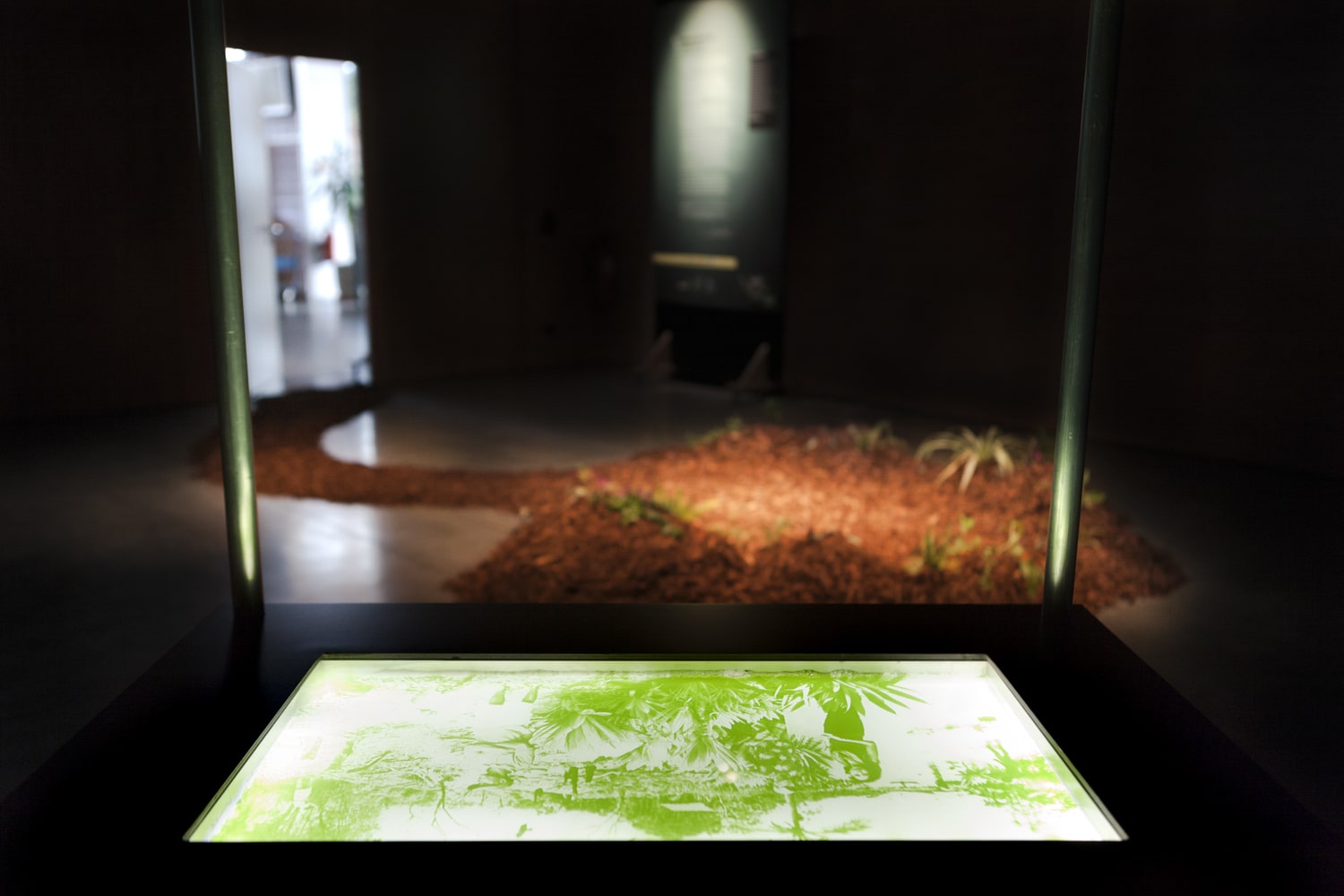

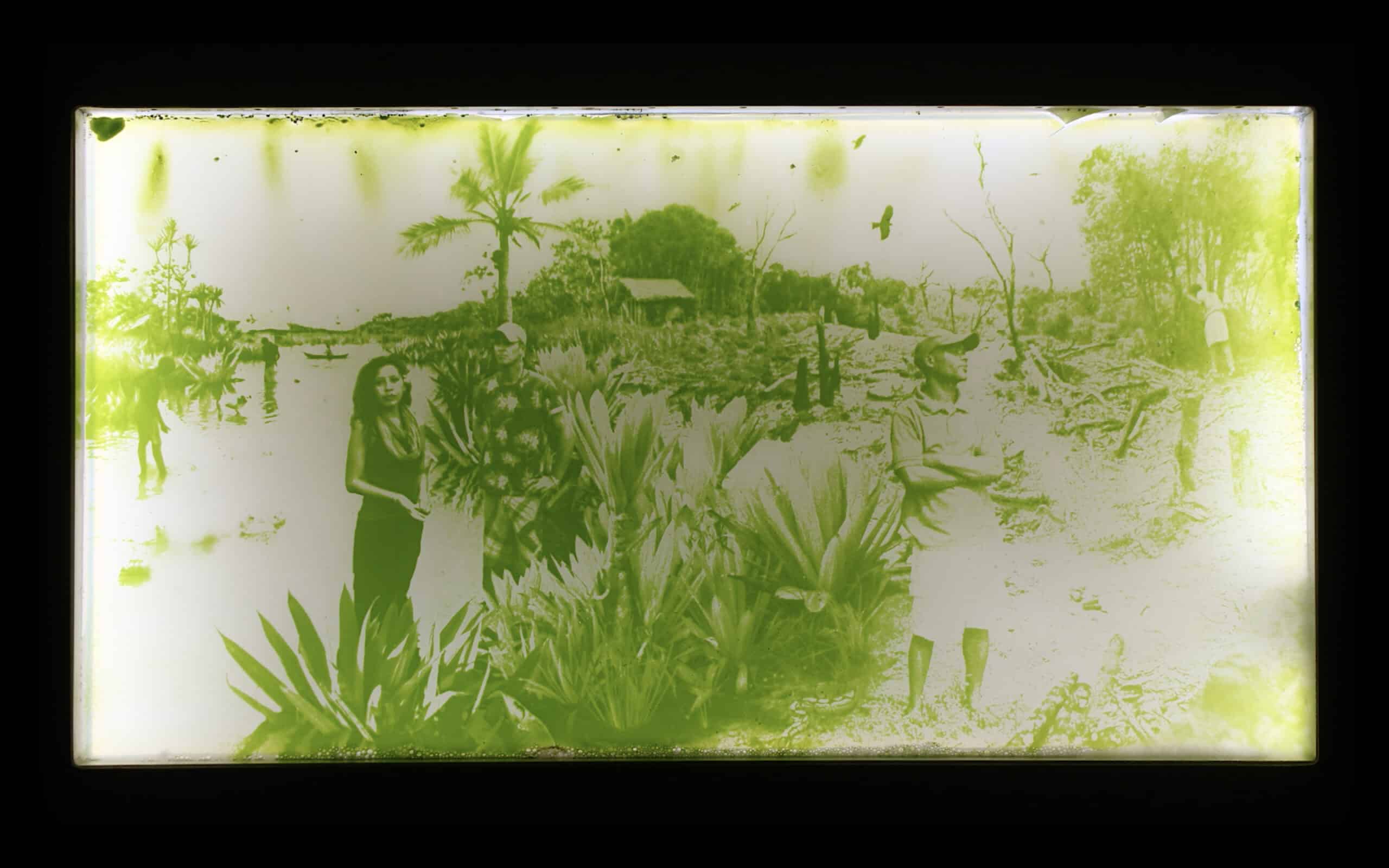

Note #5 – Fig. 12 Ecoumène V.2 : Vohibola, 2019. View of the installation at the Cube, Manach (Lux.) © Lia Giraud Écoumène V.2 : Vohibola (2019) a été développé au fil de trois expositions au Luxembourg, à Marseille et en région parisienne.

Vohibola est une des dernières forêts de l’est de Madagascar, en proie à la déforestation. Transformé par le colonialisme puis par l’exploitation intensive du bois, ce territoire naturel se raconte au travers des relations que chacun tisse avec le lieu et avec les autres formes de vies qui le peuplent.

Note #5 – Fig. 13 Ecoumène (Ecumene) V.2 : Vohibola, 2020. Video HD, 15’, 16:9. Extract of the algaegraphic film produced in collaboration with composer, Térence Meunier © Lia Giraud & Térence Meunier Dans cette installation, l’Algaegraphie est accompagnée d’un dispositif photographique qui enregistre la disparition du paysage et restitue en temps réel ce processus dans un film d’animation. Une bande-son, réalisée en collaboration avec le compositeur Térence Meunier, ainsi qu’une série de détails photographiques et d’extraits sculpturaux, nous plongent dans l’atmosphère et le récit de Vohibola.

Crédits

Écoumène V.2 : Vohibola

Conception artistique et écriture : Lia Giraud

Collaboration scientifique : Claude Yéprémian

Enregistrements et création sonore : Térence Meunier

Voix : Jean-Claude Rabeherifara, Michael Cyrille Tovohla (dit « Nabé »), Lia Giraud

Production : Parc Naturel du l’Our (Lux.), Équipe « Cyanobactéries, Cyanotoxines et Environnement » (UMR 7245 CNRS, MNHN), CRAL/DIA (EHESS), Le Cube – Centre de création et de formation numérique.

Dans sa seconde occurrence (Écoumène V.2 : Vohibola), le projet Écoumènes envisage donc la production de l’image algægraphique comme un espace de tissage « éco-techno-symbolique », où peuvent co-exister et être travaillées ensemble ces différentes dimensions, à différentes échelles.

Le projet explore des milieux sinistrés par les activités techniques humaines qui affectent biologiquement le site, mais aussi la relation psychique et symbolique que les habitants entretiennent avec le lieu. Il s’approche en un sens, de la notion de « solastalgie »46 proposée par Glenn Albrecht. Vohibola est une petite forêt Malgache en voie de disparition, située en bordure d’un canal commercial qui a facilité l’exploitation intensive de son bois. Face au désarroi de ses habitants, il ne s’agira pas forcement d’incriminer l’exploitation de la forêt qui est aussi la ressource principale et historique des villages alentours, mais plutôt d’interroger la valeur de ces gestes techniques qui, dans l’économie industrielle du bois, apparaissent dépourvus de liens symboliques et biologiques au lieu. À un autre niveau, il s’agit de comprendre comment la croyance en des entités magiques et invisibles qui peuplent le lieu ouvre un espace de médiation symbolique pour ses habitants, en permettant non seulement la compréhension et le respect des écosystèmes mais aussi une gestion raisonnée et conscientisée des actions anthropiques. Comme le remarque Estelle Zhong Mengual, « surnaturel et monde vivant possèdent des propriétés épistémologiques analogues et ainsi provoquent les même affects ». Approcher la nature par le « merveilleux » [wonder] serait selon elle l’expression d’une connaissance profonde du vivant. Par sa forme, l’image algaegraphique est en soi un milieu « éco-techno-symbolique » mettant en dialogue le vivant (micro-algues), la technique (dispositif) et un espace symbolique (l’image). Chaque écoumène travaille cette articulation en proposant un récit propre au lieu, sous la forme d’une installation algægraphique augmentée. Dans Écoumène V.2 : Vohibola, le paysage algægraphiques s’accompagne de fragments photographiques et sculpturaux qui invitent, par le cadrage, à développer une forme d’attention particulière au vivant non-humain qui compose l’image-milieu. Le processus progressif de disparition du paysage est environné d’un récit sonore qui entrelace différents points de vue, tissant les histoires humaines à l’histoire biotique du lieu, pour tenter de saisir ensemble, simultanément et dans toute leur complexité, les différentes formes de vies qui modèlent collectivement ce lieu et assurent son habitabilité. Les sons bruts enregistrés au cœur de la forêt et restitués dans la bande-son offrent une présence, une voix, aux instances non-humaines, aux réalités invisibles du lieu qui échappent à l’image. Une manière d’assumer « la reconnaissance de ce pluralisme de la vie, de cette diversité qui fait monde. »47

The ecology of the oeuvre: when image becomes a context and generates collective forms of life

While the algaegraphs provide a milieu of interlacements, it is above all in the creation of the projects which weave together visions, stories and patterns of shared experiences ,that decenterings are effectively initiated The Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis) project presents itself as a space of collective exchange around the management of images, approached from the angle of forgotten consumer goods (waste). Based on the inventory of objects recovered from the Old Port of Marseille, the project studies these image-objects made invisible by the water’s surface (screen) to bring into play a more general characteristic human behaviour with respect to anthropic productions. Our consumer goods, just like the images that we produce and devour, are subject to mechanisms of burial and invisibility. They accumulate, layer by layer, on the seabed, like in the deep web. Their latent presence is accompanied by a possible phobic reappearance, a nightmarish vision of a humanity that is the victim of its own production mechanisms, which hasn’t escaped Italo Calvino’s attention48.

Faced with the ecological problem of the image-object, the ambition of this project doesn’t so much lie in producing “images of ecology” but rather to consider an “ecology of images”, that is to say, to bring in a systematic approach which gathers together a plurality of points of views and actions which can encompass the different ways of inhabiting a subject. In the same tradition as the previous projects, Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis) brings together a biologist (Claude Yéprémian), an activist from an association (Isabelle Poitou), a sociologist (Baptiste Monsaingeon), a composer (Térence Meunier) and young artisans (professional training classes in scientific glassblowing at the Lycée Dorian) who, each in their own way, work on and study the management of residual materials: the metabolising of the pollutants by the microalgae is thus juxtaposed with the liquid glass that takes shape as it is worked on in the manufacture of the bioreactors; the sociological and historical analysis of waste comes face to face with the emotive account of the ecological struggles; The soundtrack uses audio fragments reminiscent of the process of the algaegraphic film, assembled from residual internet images. These intersections and encounters put in place what I would be tempted to call, following Peter Szendy, an “iconomy”, placing the creation of images in a space of collective management in which the rules that govern our visual production are discussed, experimented with and generate collective “forms of life”

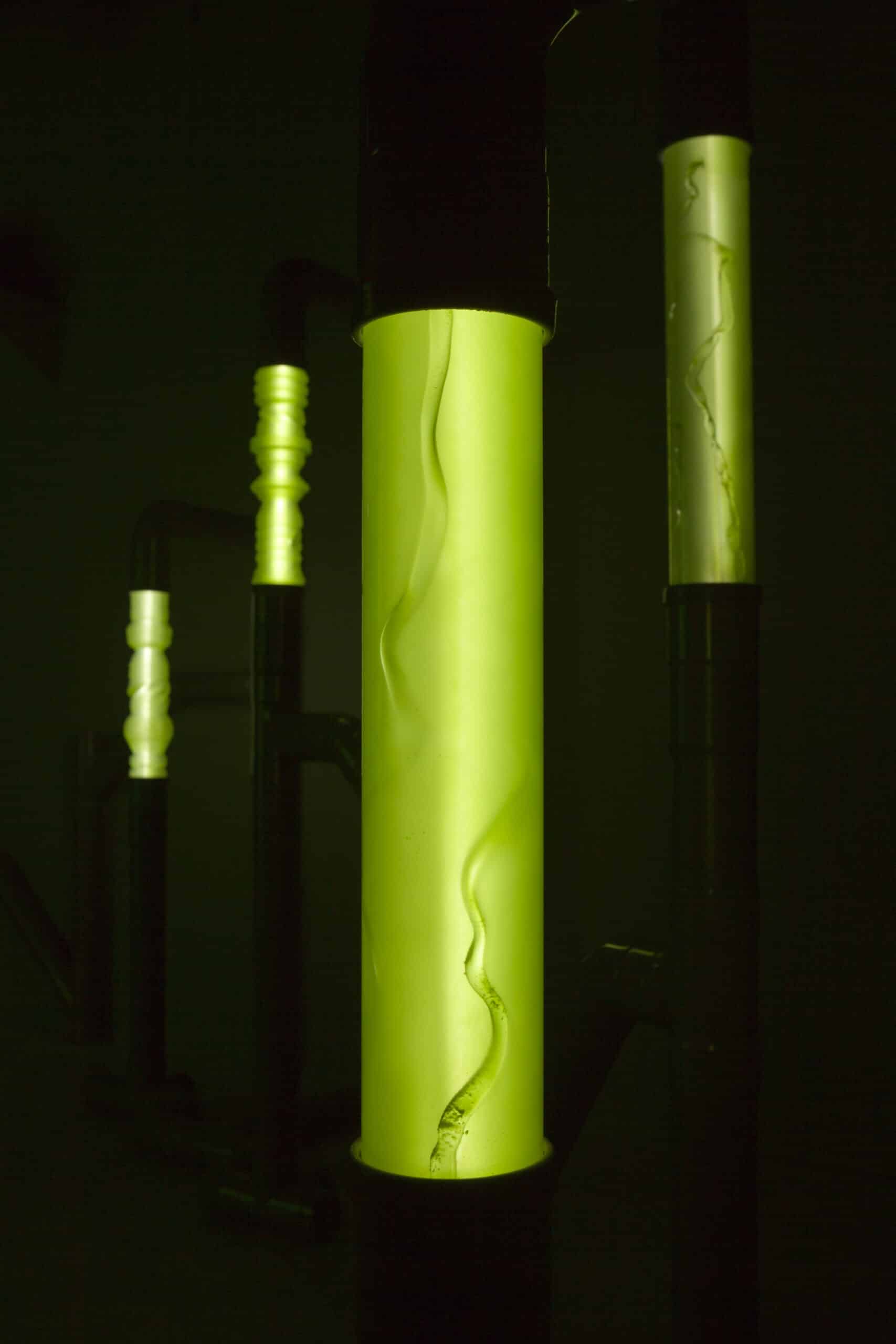

Note n°6 – Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis), 2021

Presented as a “photographic inventory of the invisible”, the Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis) project focuses on the thousands of objects fished out of the port of Marseille between 2016 and 2020 by the MerTerre association.

Note #6 – Fig. 14. Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis), 2021. View of the installation at the Hors pistes festival #16: “the ecology of images“, Centre Pompidou © Lia Giraud L’installation présentée au Centre Pompidou pour la 16e édition du festival Hors Pistes (« l’écologie des images ») se compose d’une structure tubulaire qui accueille six bioréacteurs en verre borosilicate, au sein desquels se développent jour après jour des cultures de micro-algues. Ces formes sculpturales ont été réalisées avec les élèves et professeurs de Première et Terminale du bac pro « Verrerie scientifique » du Lycée Dorian.

Note #6 – Fig. 15 Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis), 2021. Detailed view of the borosilicate glass bioreactors inside which the microalgae develop during the exhibition.© Lia Giraud Le film projeté met en scène la révélation processuelle de ces objets/images par un procédé dit algægraphique. Ces micro-algues, habituellement utilisées comme marqueur de pollution, se substituent ici au grain d’argent photographique pour dévoiler une image devenue vivante. Cette matière composée d’oubli et de réminiscences devient objet de questionnement dans la bande-son qui accompagne le film : La voix d’Isabelle Poitou, fondatrice de l’association MerTerre, se mêle à celle du sociologue Baptiste Monsaingeon pour nous guider dans une exploration intime et analytique du déchet, mise en son par le compositeur Térence Meunier.

Note #6 – Fig. 16 Photosynthèse (Photosynthesis), 2021. Video HD or 4K, 3:2. Extract of the algaegraphic film produced in collaboration with composer, Térence Meunier © Lia Giraud Le film projeté met en scène la révélation processuelle de ces objets/images par un procédé dit algægraphique. Ces micro-algues, habituellement utilisées comme marqueur de pollution, se substituent ici au grain d’argent photographique pour dévoiler une image devenue vivante. Cette matière composée d’oubli et de réminiscences devient objet de questionnement dans la bande-son qui accompagne le film : La voix d’Isabelle Poitou, fondatrice de l’association MerTerre, se mêle à celle du sociologue Baptiste Monsaingeon pour nous guider dans une exploration intime et analytique du déchet, mise en son par le compositeur Térence Meunier.

Crédits

Réalisation algægraphique et filmique : Lia Giraud

Collaboration scientifique et réalisation microbiologique : Claude Yéprémian

Soufflage de verre scientifique : Elie Amara, Damien Arondel, Charlotte Boni, Théo Borowiecki, Darren Boyeau, Ling Chen, Elie Cohen, Killian Le Yar, Raphael Lievremont, Corto Marie, Antoine Marvin, Noëlle Mattio, Ricardo Nunes, Astrid Pedone, Océane trubert, Pierre Vaillant, Anthony Vasse, Evan Valiere-Lacourt-Rivier, Mathys Vitard et leurs professeurs Ludovic Petit et David Valls.

Données sur l’inventaire du Vieux-Port : Florian Cornu, pour l’association MerTerre

Entrevue : Isabelle Poitou (Association MerTerre)

Extraits de la conférence « Homo Detritus ou L’idéal trompeur d’un monde sans reste » (Mucem, 2017) : Baptiste Monsaingeon (Université de Reims)

Enregistrements et création sonore : Térence Meunier

Observing the dancing cells together. Sharing in the biological wonder. Respecting the slow pace of biological development. Surrendering to different circadian rhythms. Experiencing a deceleration.

Bringing together philosophy and biology. Tending to microalgae day after day. Becoming a biologist-horticulturalist. Measuring the value of a life. Marvelling at the existence of a forgotten culture. Reflecting on resilience.

Allowing myself to be convinced by a plant philosophy49. Empathising with a living image preserved under a ventilator. Experiencing animality first hand. Failing in the automation of the simplest acts of care. Understanding the limits of a human technique. Rethinking the utopia of the Biosphère (Biosphere) project. Bringing together anthropology and engineering. Sharing in the concerns of the curators on the well-being of an artwork. Witnessing an affective parasitism of the living being. Accompanying the ethical reflections of the public. Gauging the shifts in conscience. Bringing together artisans and activists. Shattering the compartmentalisation of thoughts by conceiving hybrid objects. Building common ground by combining expertise. All of these gestures, these thoughts, these invisible exchanges are the breeding ground of the algaegraphs project which begins to sketch out an ecology of the œuvre in which humans and non-humans explore themselves and each other, and go on a journey, to better rethink a space that is greater than “us” 50.

Because the living image is the privileged place of a sharing of affects, it provides a permanent space in which a living community can be negotiated and redefined.

Lia Giraud

Translated from French by Jacqui Chappell

34 Augustin Berque is the creator of the term “Mesology” [http://ecoumene.blogspot.com/]. See in particular the collected papers of the conference at Cerisy, Marie Augendre, Jean-pierre Llored, Yann nussaume (dir.), La mésologie, un autre paradigme pour l’anthropocène ? Autour et en présence d’Augustin Berque (Mesology, another paradigm for the anthropocene? About and in the presence of Augustin Berque, Hermann, Paris, 2018.

35 Bernard Stiegler, De la misère symbolique (Symbolic Misery), Flammarion, Paris, 2013

36 Jakob Von Uexküll, Mondes animaux et monde humain (A foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans), Denoël, Paris, 1965.

37 Victor Petit, « l’effet Uexküll », Séminaire Mésologiques, 13 novembre 2015

38 TTerm proposed by Tetsuro Watsuji in his analysis of the human milieu (Fûdo). Tetsuro Watsuji, Fûdo, le milieu humain (The human milieu), CNRS, Paris, 2011

39 Georges Canguilhem, La connaissance de la vie (Knowledge of Life), Librairie philosophique J. Vrin, Paris, 2000

40 Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception (Phenomenology of Perception), Gallimard, Paris, 1945

41 Gilbert Simondon, L’individuation à la lumière des notions de forme et d’information (Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information), Jérôme Million, Grenoble, 2005.

42 Estelle Zhong Mengual, Apprendre à voir. Le point de vue du vivant (Learning to see. The point of view of the living being), Actes sud, Arles, 2021

43 Merleau-Ponty, Op.cit., p.103

44 Georges Canguilhem, Op.cit., p.10

45 Raymond Ruyer, L’animal, l’homme. La fonction symbolique (Animal, Man and Symbolic Function), Gallimard, Paris 1964. He writes in conclusion on p.261 “Human activity, unlike animal behaviour, is not only thematic, it is also symbolic” and further on, “Man has amassed accumulative, transmittable and reinterpretable œuvres, which are not simply organic products. He explores two worlds at the same time, the ideal world with which the animal is only in contact with by the specific instinctive themes that are proper to it and the spatio-temporal world. Each world is informed by the other. […] He deciphers all of the forms and, behind these forms, their sense or expressiveness, which he assimilates to his being. He thus becomes a double entity, with the brain uniting his psychic, structured and maintained organism, to his biological organism. Furthermore, this psychic organism, or this “soul” gradually merges with the “mind”, that is to say with universal, rather than indivudalised meanings.”.

46 Glenn Albrecht, Les émotions de la terre (Earth Emotions), les liens qui libèrent, Paris, 2020. “Solastalgia” describes a state of anxiety, distress or powerlessness felt by inhabitants who are denied the comfort of feeling “at home” when confronted with the environmental destruction of the places they live in.

47 Camille de Toledo, Le fleuve qui voulait écrire. Les auditions du parlement de Loire (The river that wanted to write, Loire Parliament Hearings), Les liens qui libèrent, Paris, 2021

48 Italo Calvino, les villes invisibles (Invisible Cities), Seuil, Paris, 1996.

49 Emanuele Coccia, La vie des plantes, une métaphysique du mélange, Payot et Rivages, Paris, 2016

50 Tristan Garcia, Nous, animaux et humains, Actualité de Jeremy Bentham, François Bourin Éditeur, Paris, 2011