This key moment in the life of artworks that exhibitions represent is documented by few. But Aurélien Mole is no doubt a different sort of exhibition photographer. An artist and curator as well, he collaborated with the historian Remi Parcollet, a specialist in exhibition views, and the artist Christophe Lemaitre, on the publication of the sixteen volumes of Postdocument, an editorial project on exhibition views, between 2010 and 2021. If there’s anyone who can weigh in on how an artwork and its exhibition create an image, it’s him.

— Étienne Hatt

What makes a good exhibition view?

A good view has two qualities. First, responding to the expectations of the art commissioner, whether formulated or implicit – this is the psychological aspect of the work. But it’s also a useful document for historians. An isolated view is thus of less interest than a series allowing to convey the exhibition through photography, moving around the space and revealing connections between objects. Remi Parcollet highlights the interest of unpublished photographs that allow for a shift in viewpoint on an exhibition.

How are exhibition views to be situated in relation to other documentary practices?

The closest practice would be architectural views, but exhibition views are quite different in that what is photographed is a symbolic transaction between artists and institutions. Some artists showing at the Centre Pompidou have asked me to incorporate the blue pipes so the museum can be identified. The same goes when a small institution invites a well-known artist. What must be rendered are these exchanges; it’s not just about walls detached from the floor. This is the difference between reproductions of works and exhibition views, which illustrate a relationship between artistic practices and places.

Cette exposition regroupait des œuvres d’artistes qui pouvaient être mentionnés comme référence au concours d’entrée des Écoles des Beaux-Arts françaises.

Are there different trends or even different schools of exhibition photography?

There are trends. The arrival of screens and Instagram, for example, has led to requests for images that are much cleaner, almost clinical. But it’s not a question of schools, because the technique used is what determines the image, to a great extent. Some photographers don’t add lighting, and use Photoshop for retouching. I personally use a flash. The techniques are personal; they’re not signs of belonging to a school. Not to mention, exhibition photography is a minority and solitary practice. When I was at the photography school in Arles, it wasn’t even mentioned as a job prospect. I discovered it through a training program on exhibitions, and the creation of a curator collective, Le Bureau/. With the technical know-how at my disposal, I documented our exhibitions.

How does a photoshoot session play out?

It depends on the art commissioners. Some only call upon my technical know-how. In that case, I’m an operator at times, to simply take photos improving upon what the artist or commissioner shows me on their phone. But through the experience I’ve developed around exhibitions and their documentation, others call upon my point of view. In any case, it always starts with a visit to the exhibition. Walking around, I try to understand the exhibition as originally imagined, before it collides with reality. If the result is substantially different, I look to how to fill in the gaps. For example, if a particular lighting design is not so visible the day of the shoot, I intensify a color to obtain a truer exhibition view than the one I see.

But it’s not a question of photographing an ideal exhibition that doesn’t exist in reality?

Let’s say that I intensify the intentions so that they correspond to the project. Keep in mind that nothing will remain of it except the photographs. They may not be a strict document, but they shouldn’t betray it either.

A session is an exercise in adaptation. You don’t come with a protocol.

When I cover several exhibitions in a row for a given institution, I grow accustomed to the place, and I operate more quickly. Elsewhere, I have to take the time to understand how the site functions in photography. The more you practice, the more ways you have of working that simplify the process, but I constantly need to adapt them.

Manchette exhibition at Samuel Gassmann in 2023, photograph by Aurélien Mole.

View of the collective exhibition Working Forest at Galerie Dohyang Lee in 2014. Photograph by Aurélien Mole. L’exposition « La Forêt Usagère » regroupait l’ensemble des collaborations entre Aurélien Mole et d’autres artistes : Åbäke, Jesus Alberto Benitez, Roxane Borujerdi, Nicolas Chardon, Aurélien Froment, Hippolyte Hentgen, Charlie Jeffery, Raphaël Julliard, Pierre Leguillon, Christophe Lemaitre, Colombe Marcasiano, Niels Trannois, Clément Rodzielski, Izet Sheshivari, Olivier Soulerin, Syndicat, Eva Taulois, Julien Tiberi, Cyril Verde.

What are these ways of working?

For example, my approach to lighting. In the beginning, I worked without flash. Then I realized that lighting conditions weren’t always great, so I added lighting. Today, I use flash almost all the time. It allows me to be more accurate in terms of the colorimetry of the works, and it simplifies retouching. I don’t necessarily need to desaturate the walls. That’s my way of working; it’s what produces the type of images with which I’m associated.

I’ve seen you photograph a piece in a fair and was struck by how quickly you work.

Oftentimes, I’m familiar with the works. I know how they’ll appear in photographs. More generally, I have to work quickly because my exhibition view practice is part of a longer project aimed at constituting an archive; and like any archive, the meaning only comes from having a substantial volume. So I need to cover a lot of exhibitions – sometimes six or seven a day, not always so big – to be able to document contemporary creation in France, all over the country. I’ve been at it for fifteen years, and I must have covered 8,000 exhibitions and compiled 180,000 to 200,000 images.

What do you intend to do with this archive?

I’m not yet sure but I can see the potential. With other photographers it would be possible to create a collection devoted to exhibition photography.

Your archive resonates with the Postdocument project. Is this still ongoing?

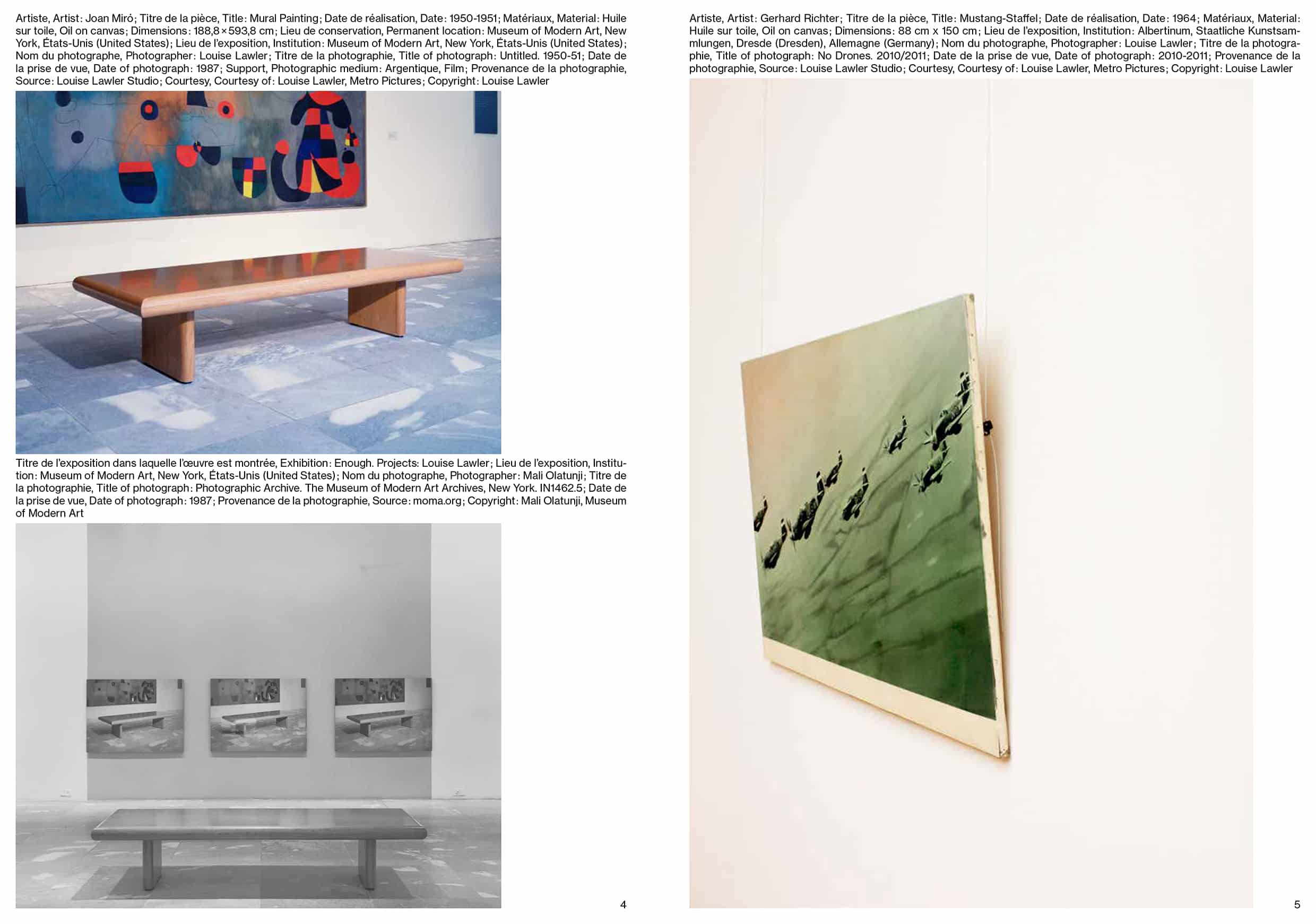

The project ended in 2021, not because our motivation had died down, but because it was time to end it. This editorial project on exhibition views was undertaken with the historian Remi Parcoll and the artist Christophe Lemaitre. Originally, Remi was preparing his dissertation on exhibition view photography. He had a FileMaker database encompassing views that could be sorted by many different criteria. We sought to make use of this relationship to the photos not individually, but as a broader set, with the idea that the more information there is on a photo, the more this will change how we view it. We thus created a caption system comprising sixteen predefined entries: artist, title, date, material, dimensions, permanent location, exhibition, institution, photographer, title of photograph, date of photograph, photographic medium, camera, source, courtesy and copyright. The idea was to zoom out, from the object all the way to the photo rights. We put out sixteen issues, one for each entry. The first, which came out in 2010, was devoted to “Title of the piece”, and gathered views of Untitled (Stack) by Donald Judd, a piece shown in many institutions because multiple copies of it were produced. We collected a lot of images, historical photos from the Castelli Gallery, others from various sites like Flickr. We had enough material to literally go all the way around the sculpture. The second issue was on materials. We chose views of works produced using reflective material, in which the photographer appears at times, because prior to digital, the operator couldn’t be concealed. It took us twelve years to produce the sixteen issues. Starting with the eighth issue, we sought to professionalize the publication, making it bilingual and entrusting the design to Spassky Fischer. In 2015, they created a reader compiling the first seven issues alongside the eighth. Postdocument ceased to be a fanzine, and its reputation grew. The eighth issue, devoted to the “dimensions” entry, encompassed views of works shown in postindustrial spaces. The idea was to show how the ghost of large-scale industrial production floats over works that are subsequently presented. The last issue, in 2021, was on the shoot date. We contacted photographers from around the world and asked them to photograph a single work in public space over different seasons. Every time, we wanted to play with initial constraints to provide a fresh viewpoint on exhibition photography. Exhibition photography is often a footnote in art history, but we wanted to inverse things, to show that things could happen through exhibition views, that these are how exhibition history is written.

Is all contemporary art photographable?

There are always tricks to documenting a work. In the case of sound works, like those of Dominique Petitgand, for example, the presence of a figure in the photo portrays listening. Every piece can be photographed, unless it aims not to be, by going against any form of documentation, as in Tino Sehgal’s works; he favors the experience of a work over that of a document. But even in this refusal of images, they are present; stolen photographs taken with a phone are a form of unofficial documentation.

Is a photography exhibition easily photographable?

The Thomas Demand show now on at the Jeu de Paume is! When the formats are smaller or the images are more classic, the photography focuses more on the relationships between works, between formats. You need to be able to show the importance of a series, while getting closer in to isolate the most meaningful photographs. You highlight prominent architectural elements, openings. You reframe, you produce images within the image. The work of positioning is much more important. It’s often less exciting than exhibitions bringing together different media, and there are other constraints, like shiny paper or framing glass.

What camera do you use?

A Nikon D850. View cameras are too slow for the short timeframe required for exhibition views. I still use a reflex rather than a bridge camera, which all the professionals are using now. A bridge is a more compact camera that offers instant correction and a live screen view of the photo. With my reflex, I don’t see an image, but two mirrors. This is important to me, as a reflection opens up more possibilities than an already fixed image: I think and compose differently. I’m extremely free in the translation of reality that I’ll undertake, whereas a bridge automatically produces a pre-translated image. Bridges mark a shift in photographer habits. They’re seen as technical progress, but the images produced, reaching a median level, are already highly interpreted and polished. Conceptually and technically, bridges do the opposite of what I’m currently doing.

What does postproduction entail?

A lot of retouching; sometimes several shots are edited together to make a good view. When I use a flash, I have to move it to avoid reflections before combining images. If need be, I desaturate the walls to create a neutral environment and I correct the perspectives, especially when the spaces are irregular. To give a cleaner aspect to spaces, I erase emergency exits and electrical sockets, and sometimes even redo the floors. These are details you pay no attention to during a visit, but they leap out to photographers.

Impression pigmentaire contrecollée sur aluminium, avec cadre en Noyer. Poids en laiton. 130 x 90 x 12 cm

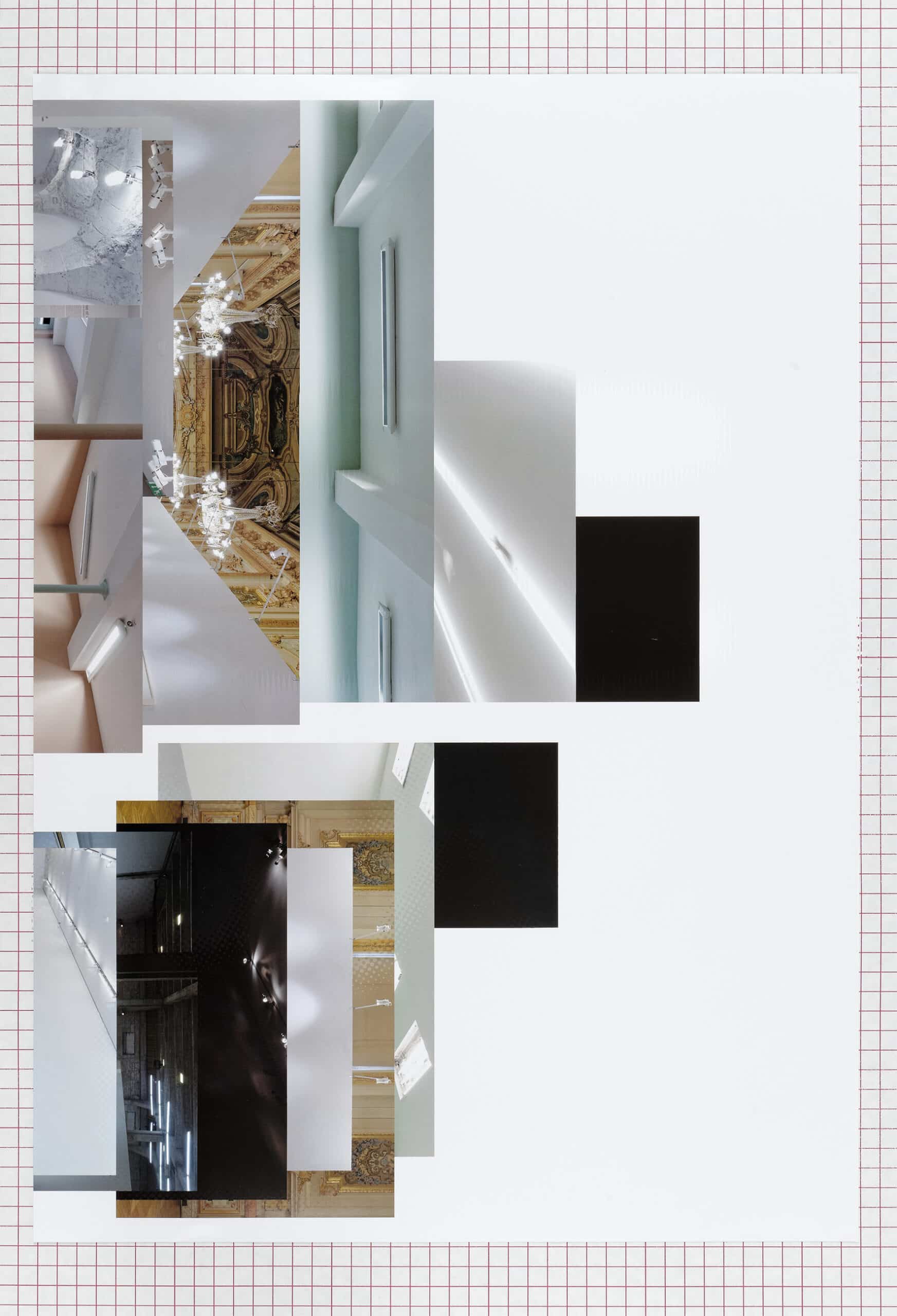

Stèle est une pièce réalisée avec le collectif Syndicat (François Havegeer et Sacha Léopold). C’est tout d’abord un collage numérique réalisé par Syndicat à partir de photographies de vues d’expositions réalisées par Aurélien Mole.

Chaque collage a pour sujet un cas limites de restitution photographique, que celui-ci concerne les couleurs, les sources lumineuses ou les textures.

Aurélien Mole and Syndicat, Light Stela, 2015

Une fois ces collages réalisés, Syndicat les a envoyé à 5 imprimeurs différents installés en France, Belgique, Lituanie et Chine pour les imprimer sous forme de poster.

À la réception des ramettes de posters, et ce malgré les fichiers identiques, aucun des posters ne présentaient les même rendus de densité ou de colorimétrie.

Fort de cette constatation, Aurélien Mole a ensuite re-photographié chaque poster. Chaque série a ensuite été empilée numériquement et Aurélien Mole, François Havegeer et Sacha Léopold ont découpé dans cette épaisseur digitale des motifs qui n’apparaissent que parce que les posters, bien qu’issus du même fichier, ne présentent pas les mêmes caractéristiques de rendu.

Impression pigmentaire contrecollée sur aluminium, avec cadre en Noyer. Poids en laiton. 130 x 90 x 12 cm

View of the exhibition “Sir Thomas Trope” co-created with Julien Tiberi at the Villa du Parc d’Annemasse in 2013 Photograph by Aurélien Mole. Cette exposition réalisée sur des cimaises tournantes avec des œuvres elles-mêmes placées sur pivot pouvaient être entièrement reconfigurée par le spectateur.

Is an exhibition photographer an author, as opposed to a mere operator?

I am paid as an author (cessions de droits d’auteur in the French system). Beyond these administrative considerations, you can be an author of exhibition views, with a specific gaze. I’m familiar enough with the work I do and contemporary creation to propose a viewpoint on exhibitions, even if this is guided by a request. My work ethic draws inspiration from two people whose work I admire, Jean Prouvé and Walker Evans. The former developed an integrity in design, an effort to combine the constraints of a material and the function of an object in transparent fashion. The latter constructed conditions of objectivity in personal fashion through the development of what is called “documentary style”. These two artists are considered authors, and as my work falls in line with their approaches, I also consider myself to be one.

Is it possible to do the work of an artist as an exhibition photographer?

This isn’t what’s asked of us. But artists like Louise Lawler do exhibition view work. We even put out an issue of Postdocument with her, in which she’s listed in both the “artist” and “photographer” entries on the same photos. When she’s listed in the “photographer” entry, the focus is on the documentary value of her images.

You have also done work as an art critic. Are exhibition views a form of art criticism?

Baudelaire said that critics must be partial; and a form of neutrality in viewpoint is asked of exhibition photographers. I make no judgements. Some exhibitions are less successful, but this shouldn’t appear in my photos. Exhibition views are laudatory. Part of what art critics do, in contrast, is attempt to reproduce the intentions and translate the experience of an exhibition. In thinking about the form of criticism I’ve practiced, which favor a highly descriptive approach, to orient paths of thinking and draw conceptual lines, I can clearly see ties with my practice around exhibition views.

You’re also an artist and curator. Do you anticipate the images that will be made of the work that you produce or the exhibition that you create?

Everyone anticipates this, but my way of curating is intuitive and stems from the encounter of works and places. I rarely work using a plan; my starting point is generally from the works once in they’re in the space. I don’t anticipate, but bit by bit, I know what I’m striving for, because my imagination is marked by exhibition views. For my solo exhibition at Passerelle, in 2015-2016, where I had photographed a lot of other artists’ exhibitions, I took into account the difficulties I had encountered to produce an exhibition that would be interesting to photograph in itself. I made reference to a number of elements from exhibition history, such as Galerie 291 or the Grande Galerie of the Louvre painted by Hubert Robert. In 2019, for the exhibition Un être, un acte, un lieu, un objet (A Being, An Act, A Location, an Object) at FRAC Nouvelle-Aquitaine, in Bordeaux, Éric Tabuchi and I had the idea of hanging the works in the center of the modular walls, even creating overflow up toward the ceiling. We understood that the exhibition lay therein, because of the images that could be made in this way.

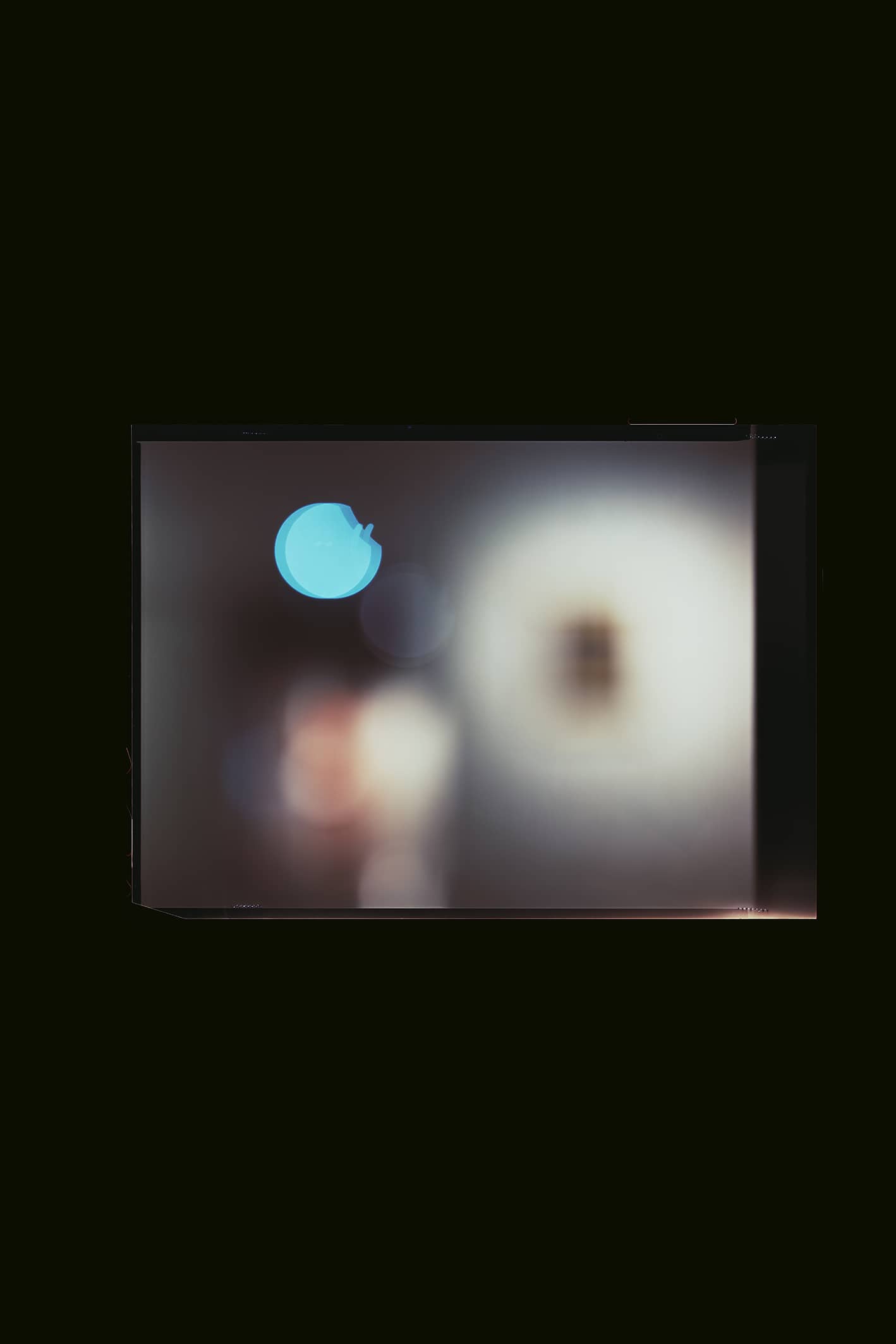

Tirage Frontier sur papier Fuji brillant d’après fichier numérique de négatifs argentiques scannés.

24×36 cm

Tain est une série de 9 images réalisées en chargeant des appareils photos conservés au musée Nicéphore Niépce de Chalon-sur-Saône avec du négatif film. Pour la prise de vue, les appareils sont laissés en l’exact état dans lequel ils sont conservés, aucune mise au point n’est faite et ils ont la même position qu’ils occupent dans la vitrine. C’est donc le point de vue de l’appareil depuis la vitrine du musée et par extension, le point de vue de n’importe quel artefact conservé et exposé dans un musée.

In 2019, for the Tain series at the Musée Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône, you produced a series of works taking the form of exhibition views.

I used the cameras placed in the museum display cases, loading them with light-sensitive material. This time, there wasn’t anybody behind the images. They are exhibition photographs with no operator, and no viewpoint other than that of the camera.

Interview by Étienne Hatt, march 2023

Translated by Sara Heft