Erotic photography is subject to two widely held assumptions that tend to confine it to the category of minor arts, which are the following: firstly, sexual arousal is not related to aesthetic response, and secondly desire works as a distraction from contemplation. In a nutshell, if I desire the object represented, I do not see the work of art.

Yet there are erotic photographs, taken by great names in photography who have never seen themselves refused the title of artist: Man Ray, Robert Mapplethorpe, Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman, Andres Serrano and Jeff Burton, to name but a few. When George Bataille fervently asserted that “nobody doubts the ugliness of the sexual act”1, he was referring to the deprivation of the status of artwork suffered by these depictions of eroticism. Yet, how can that be asserted, when a number of photographers have successfully represented the beauty of sexuality? The history of art has been linked to desire since its very foundation: paintings of nudes were hung in bedrooms to arouse husbands and wives’ desire. It is said that the first portrait was made by a woman in love tracing the outline of her lover’s shadow on a wall, and that the possible role of prehistoric callipygian statuettes was to stimulate fertility. Nor does photography escape the prerogative according to which mankind tries to portray sexuality through all the means he has to hand: erotic photographs have existed since photography was invented, and the first examples that have been preserved date from the 1840s. All of these examples show that Bataille was wrong and when he wrote these lines in 1952, he was perfectly aware of the erotic photographic works by Man Ray and Lee Miller, of the nudes by Edouard Weston and the photo-erotic works of Pierre Molinier, to whom he was close. Why, in this case, did he voluntarily disregard the aesthetic significance of eroticism? This is what it is important to try to uncover, in a story of desire, trigger, and distraction.

Distraction

When I look at an erotic photograph, my sensitivity is immediately challenged. It is true that my senses are stimulated, from a highly physical viewpoint. The old adage, which says when the cavernous bodies are irrigated, the brain is less so, is perhaps behind the refusal to see art in erotic images. We can thus see how it could be envisioned that the sexual content of a photograph may distract from the art.

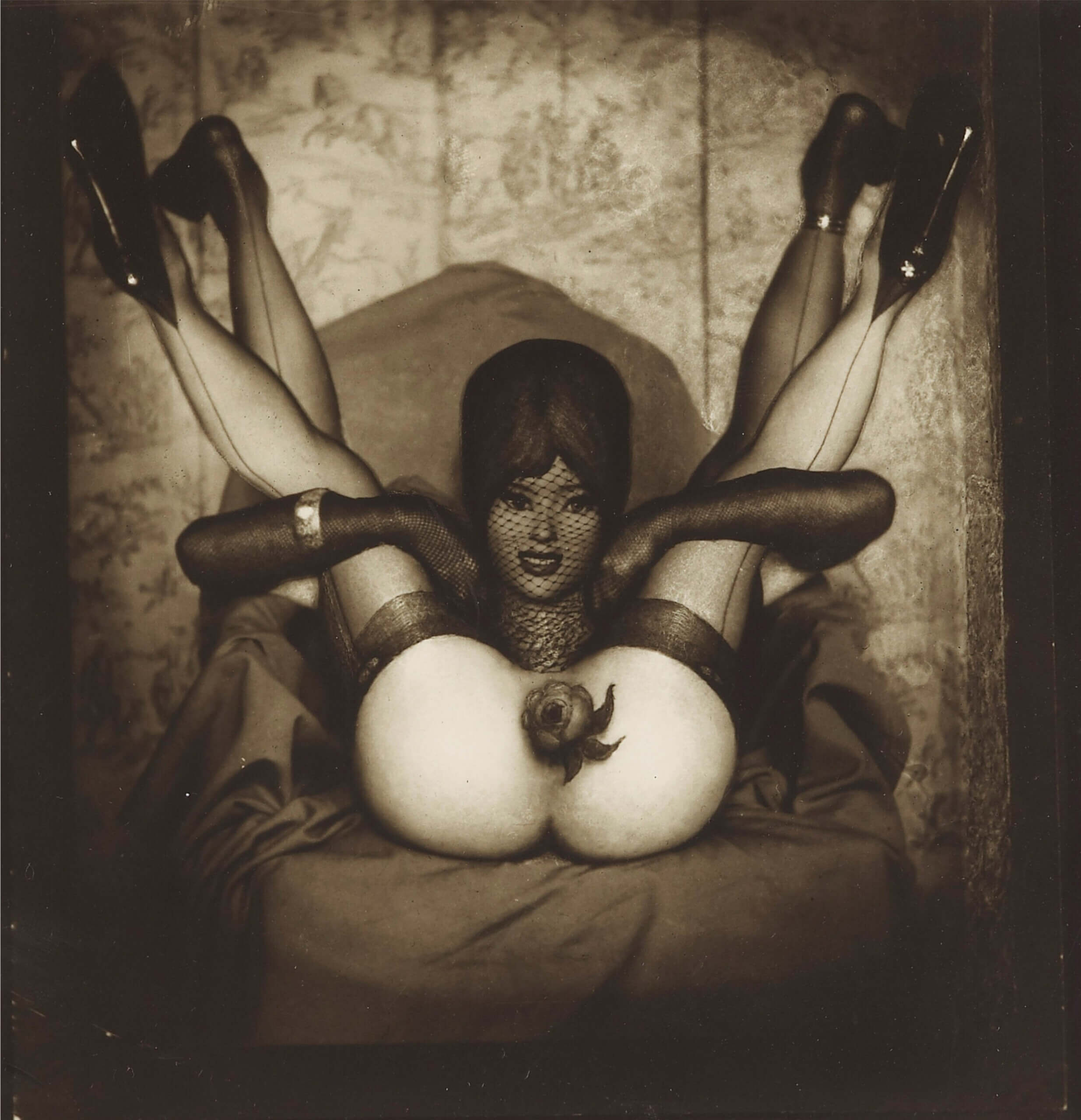

But an erotic photograph is never solely erotic. It uses codes and symbols that have been handed down through generations of the history of art and the history of eroticism. There is, of course, a stereotyped imagery of the Eros, comprising nylons stockings, shapely legs, and particular poses that immediately appeal to the collective imagination in respect of staged and sophisticated sexuality. In this perspective, some photographs are a reaction to each other, in the same way that, in painting, each period uses the codes and symbols of the preceding era. There is truly an erotic culture that makes the subject a legitimate topic worthy of study. But on the other hand, the images that do not use this classical imagery offer a variation on the subject, and this twist is erotic in itself. The sole example of erotic photography that Roland Barthes mentioned in La Chambre Claire was precisely a photograph by Mapplethorpe, the self-portrait with an outstretched arm, that Barthes found to be “joyfully pornographic” but which does not show the sexual act:

Erotic photography, on the contrary (and indeed this is the very essence), does not make sex the central focus. It may well not show it. It takes the viewer out of his own environment, and that is how I bring the photo to life and the photo brings me to life. The punctum is thus a sort of subtle other world, as if the image were launching desire beyond what it was showing: not just towards “the rest” of the nudity, not just towards the fantasy of an act, but towards the absolute excellence of a being, its body and soul entwined.2

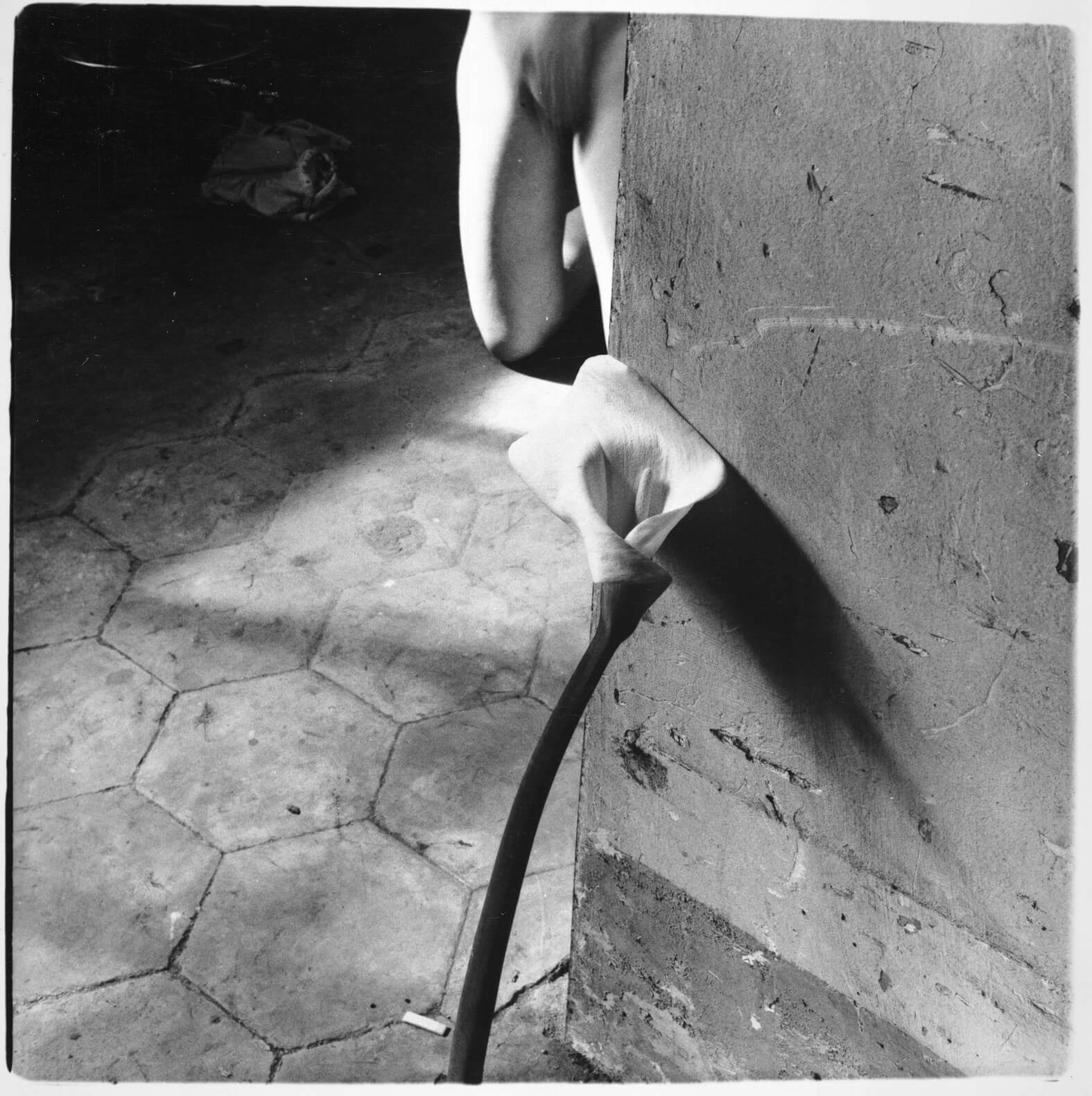

Because whatever the visual treatment of eroticism in photography, it is the detail that appeals to my sex. Barthes opposed studium to punctum, establishing that the studium of a photograph (that which, in the image, aroused my interest) is worth nothing unless there is a punctum (a point, a detail) to stimulate my emotions. Yet is its possible to suggest that erotic photography is entirely punctum, and that the studium evaporates into the emotion itself. Because it is also the detail that contains the Eros: the droplets of sweat on the forehead of Jeff Burton’s porn star, Araki’s hand grasping the ankle, the skin texture of Lisa Lyon photographed by Mapplethorpe… Yet, “distraction would seem to be the displacement of interest stirred by another detail in which it may can caught up”3. Hence, the detail that catches my attention in erotic photography also provides me with a chance to meditate on aesthetics and shape.

Because the back and forth between attention and distraction, which is the heart of the aesthetic experience, is perhaps at its peak in the case of erotic photography: I am constantly caught up in the desire to touch this skin, to be part of this scene, but it is effectively the image and its composition, that is to say the photographer’s artistic vision, which makes this desire possible. The more I look at this photograph, the more the “art” becomes apparent to me. As Patrick Baudry said in his work on pornographic images, “The sexual intensity of the sexual image is just a first fleeting moment. As soon as it has been seen, the X-rated image no longer maintains that prestige. For a brief moment, the pornographic image short circuits critical abilities. At the very moment when the image is discovered, the eye is filled, flooded, and shut off. But once the eye has seen the image once, it can never again see it the way it was first seen, with such blinding potency. That is precisely it: “seeing it again” obliges the onlooker to actually start to see it and to look at it.”4

It could even be said that this physical desire, this emotional tension makes my attention even more precise, even fuller. Baudry said exactly of erotic images “if they captivate, it is precisely because they allow the onlooker to free himself of caring about possession”5. The look in an eye that is viewing an erotic photograph will be attentive, tense, and animated by desire. If we define distraction as desiring attention6, then, yes, erotic photography is a distraction, insofar as it is effectively this sensual yearning that underlies any encounter with erotic photography. Yet it is precisely that notion of desire that vilifies erotic photography by refusing to allow it the privilege of what may be called disinterested pleasure. But what is it in the work that makes it desirable? Do we desire the object or its representation?

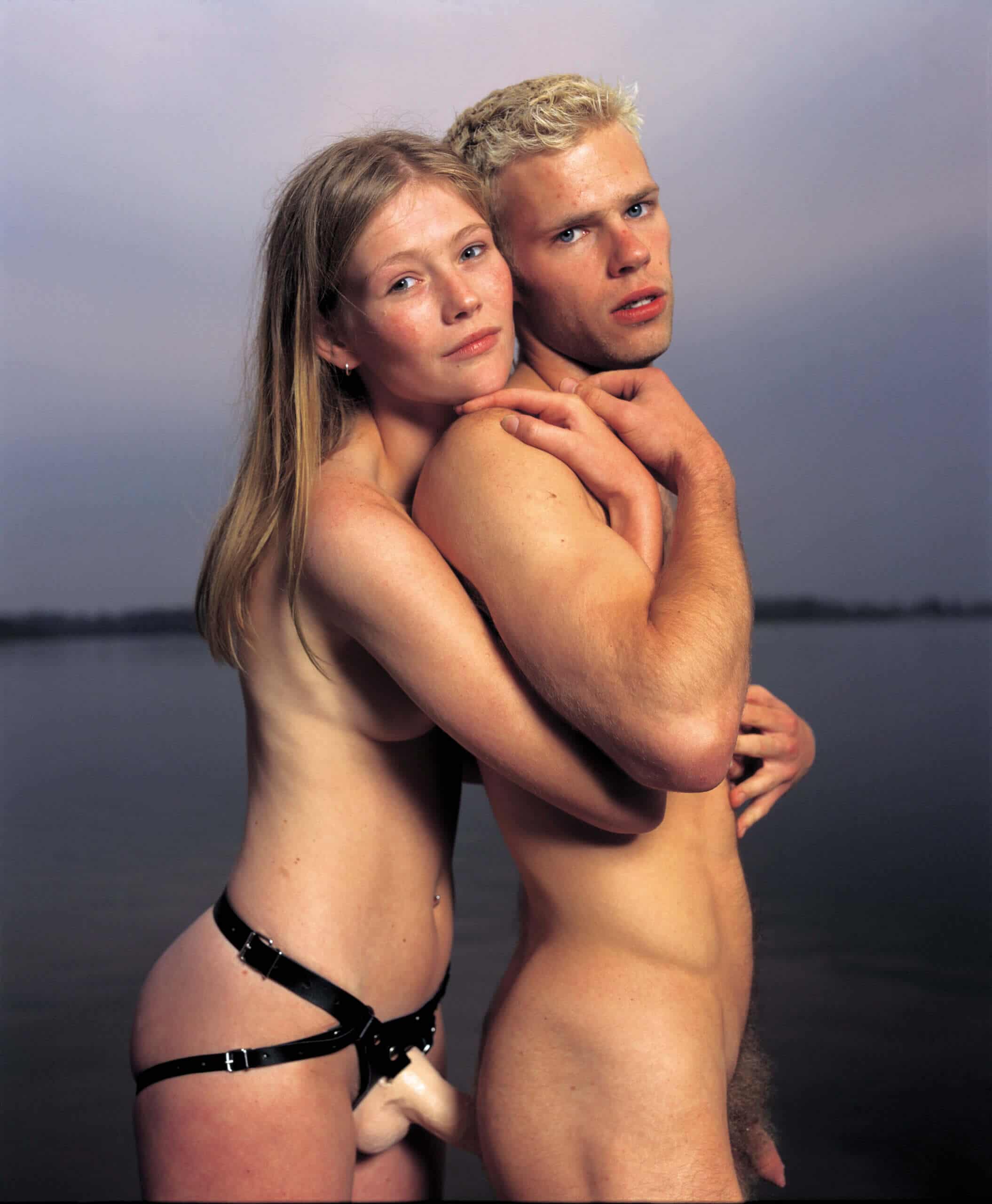

Courtesy of the artist and Nathalie Obadia gallery, Paris/Brussels

© Andres Serrano

Desire

It would be dishonest to say that desire is not at work in the relationship with the artistic object. It is effectively the search for pleasure, whether aesthetic or intellectual, that motivates people to spend time with works of art. It remains to be seen what desire it is and what pleasure is brought into play. The question could be summarized as follows: is sexual desire different from desiring the work? If I desire the object portrayed, am I distracted from being receptive to the aesthetic aspects?

Erotic photography is often set apart. It is as if we deny the aesthetic qualities of images designed to arouse sexual desire. “It’s solicitation”, we say, thus implying that desire is easily triggered and easily felt. But nothing is less sure. Desire and sensual preferences are so diverse that it isn’t sure that a photograph conceived with the goal of arousing the senses would manage to do so. On the contrary, desire may show itself, freely, without having been guided. Everyone may desire exposed bodies, and whoever wishes to remove all desire from a photograph of a nude would need to be particularly insightful! There is always someone who will find a body to his taste. The place of sexual desire in erotic or pornographic photography is not so sure, and its existence is not guaranteed.

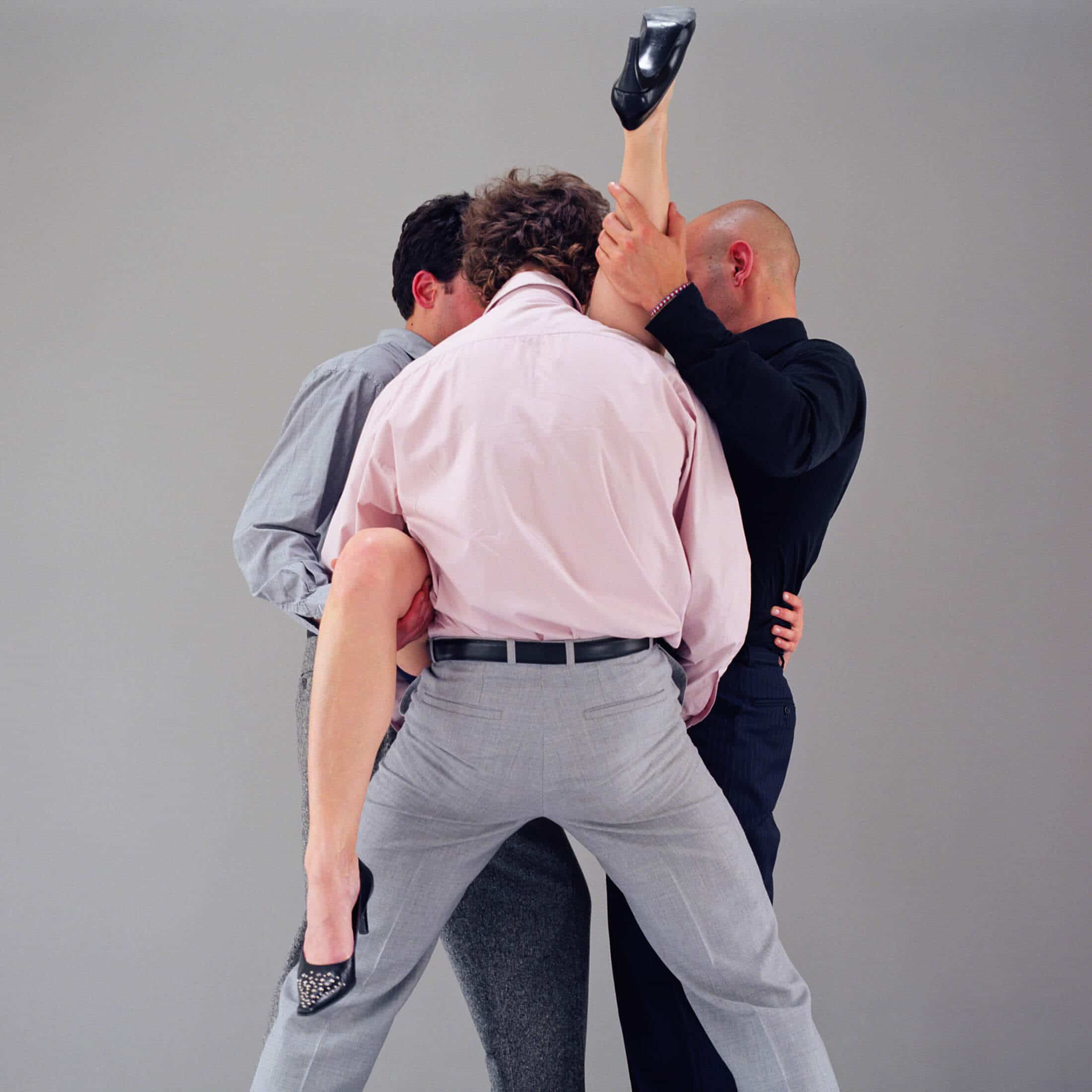

Yet, what is guaranteed, and what we therefore look at in an erotic photograph, is the photographer’s desire. It is his choice of the moment, this composition, this detail, this punctum that stimulates his desire, and that he shows for us to see. Whether our sensuality is stimulated or not, it is this choice that piques our curiosity and our sensitivity, and that our own desire confronts. This dialogue of sensitivity is erotic in itself but also fundamentally aesthetic. The taste we may have for a particular work also draws on the perspective of this intersubjectivity. Perhaps that is where the distinction between eroticism and pornography comes in: pornographic photographs do not show the photographer’s desire but an image of the desire that the photographer ascribes to the public. Edouard Levé’s series Pornographie highlights exactly that fact, by showing scenes that are expected to be part of pornographic imagery but with the difference that the actors are fully dressed. But the use of stereotypes and incongruity does not eliminate the erotic content: on the contrary, this is a game that reinforces desire and the aesthetic pleasure is coupled with a voyeuristic pleasure that comes from recognising scenes previously encountered in the pornography industry.

2002 © ADAGP, Paris 2022.

Courtesy The Estate of Édouard Levé / Galerie Loevenbruck, Paris.

More generally, the heart of the distraction/contemplation distinction is to be found in the notion of pleasure. In Kant and in traditional aesthetics, the idea of disinterested pleasure long deprived aesthetics of sensuality. In this viewpoint, “noble” (disinterested) pleasure was considered as coming from contemplative reception, and “lowly” (interested) pleasure as coming from distracted reception, that which calls out to my body and my desire for possession. But am I distracted from the art because what I see appeals to my senses? To saying that erotic desire distracts from reception, is to re-establish the archaic hierarchy between the legitimate and illegitimate senses, which date from Kant and Schopenhauer. The “noble” senses such as sight and sound would apparently be opposed to “minor” senses such as taste, smell, and touch, which are apparently not able to provide an aesthetic experience. Yet performances, conceptual art, interactive art, gastronomy, and olfactory art have all placed the senses, touch, and sensation back at the centre of reception. Why would sensual desire be excluded again from this equation? It is possible, of course, to remain in the desire of the object, without dwelling on the work’s plastic qualities. But desire invites one to dwell. You cannot possess an image. Therefore, this frustrated desire to touch may become a desire to consume through vision. What better way to really see? The desire for the object catches the viewer’s attention, whilst the indifferent viewer barely scans the image with his eyes.

© Estate of Francesca Woodman/Charles Woodman / ADAGP, Paris, 2022

In the same way, if distraction is opposed to contemplation, then erotic photography is not a guarantee of distraction: you can look at erotic image whilst maintaining your attention on it, even it if arouses your desire. When I look at Antoine d’Agata’s blurred images, I see nothing to do with any sexual act. I can only surmise or imagine it. But it is this play on imagination that creates both aesthetic and erotic pleasure. Perhaps we even imagine the act of creation that gave rise to these images, and that idea participates in the aesthetic pleasure by calling into play the spectator’s imagination.

Trigger

Let us consider the way in which photographs are taken. The photographer’s body is indeed present in the image through the artist’s presence when the photograph is taken, and through the very gesture itself of taking the snapshot. The photographer’s presence as a whole is questioned, not just that of his eye. When he considered the action of taking a photograph, Barthes realised that the eye is even rather secondary:

For me, the Photographer’s organ is not his eye (it terrifies me), it is his finger: that which is linked to the triggering of the lens, to the metallic noise of the shutter (when the camera still has a shutter). I love these mechanical noises in an almost voluptuous way as if, in Photography, they were the very thing – and the only thing – that my desire clings to, breaking into the deadly shroud of the Pose7 with their brief snapping noise.

It is not by chance that Barthes spoke here of voluptuousness: the body and senses are involved. The finger is used to take a photograph and touch plays its part. In the words of Emmanuel Hocquard in his book on nudity in photography, “Sight and touch go together, nudity touches and sees”8.

This emphasis on touch may seem surprising in the case of an art that is only perceived using sight, yet the idea is not knew. A certain reconciliation between the senses of sight and touch may be found in the notion of “haptics”, which dates from the 19th century. Introduced by Aloïs Riegl in 1899 and originating in haptomai, “touch” in Greek, the term aims to come as the counterpart to the term “optical”, and express the idea that there is a prolongation of the hand to the eye in aesthetic reception, and that it is in touch that all aesthetic perception has its roots. In Grammaire Historique des Arts Plastiques, he recalls that of all of the five senses, touch is the most reliable:

That of the five senses that man uses to receive impressions from external things – sight – is rather apt to mislead us as to the three dimensions that we see. Because our eye is not capable of penetrating bodies and therefore only sees one side presented to it as a two-dimensional surface.9

Untitled #229 (at Herb Ritts’), 2007

Chromogenic print

40 x 60” / 101.6 x 152.4 cm. Edition 1 of 5

© Jeff Burton

Courtesy of Casey Kaplan, New York

Therefore, aesthetic appreciation cannot overshadow this sense. On the contrary, for Riegl, it is in the sensations of touch that we find the origin of the aesthetic experience:

It is only when we use the experience of touch that we mentally complete the two-dimensional surface seen by our eyes, thus making it a three-dimensional shape. This process will take place all the more easily and quickly when the object contemplated presents aspects that are likely to remind the memory of experiences of touching.10

We, therefore, glimpse how sexuality may be one of the origins of art. The sexual experience, during which caresses, clutches, and embraces are paramount, brings into play the sense of touch, in a relationship between hand and eye, in the sense of the relationship between what is seen (the body of the beloved and desire) and what is touched and felt. In that, the notion of haptics allows us to encompass sexual pleasure in the aesthetic: what we see, we also touch, at least in our minds, and erotic photography celebrates precisely that aspect of aesthetic reception. Barthes in La Chambre Claire explained to what extent the body is subject to this confusion between sight and touch: “A sort of umbilical cord links the body of the thing photographed to my eyes: here, light, although intangible, is a carnal medium, a skin that I share with the one who was photographed.”11 Whatever we do, photographs are carnal. Erotic photography, suffused with touch and haptics, may succeed in bringing together the desire to climax and the desire for beauty, without the latter being diminished.

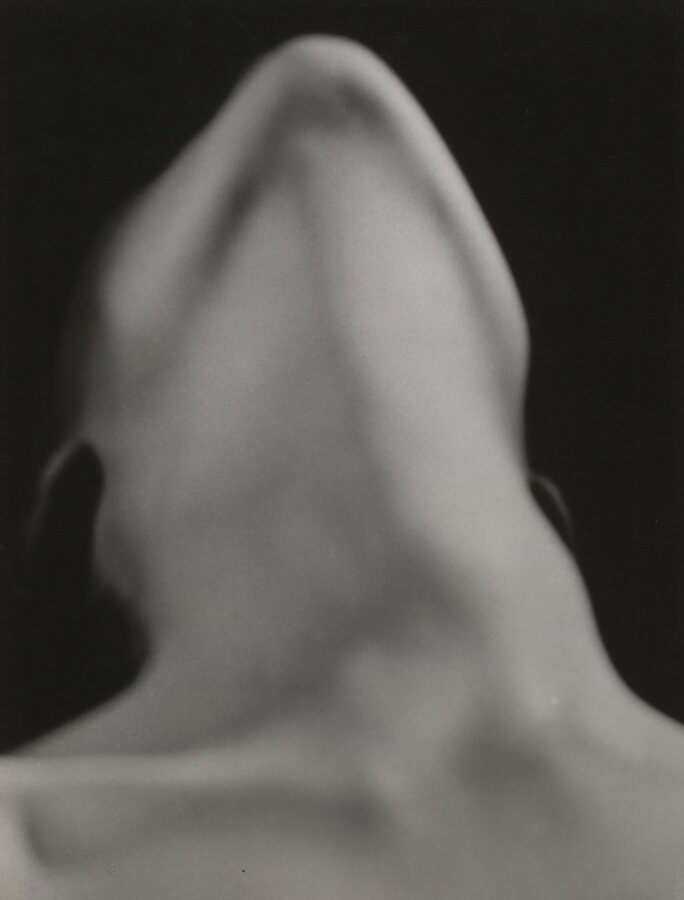

![Nude bent forward [thought to be Noma Rathner]](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Copyright_LeeMillerArchives_Nude_bent_forward_thought_to_be_Noma_Rathner_Paris_France_c1930.jpg)

As a paroxysm

A photograph may be erotic even if it does not represent any form of tangible reality. The difficulty of settling the question of erotic distraction lies mainly in the difficulty of defining what constitutes an erotic photograph. Hans Bellmer in his Petite Anatomie de l’Image, suggested an experiment that allows one to step back from the notion of representation:

You place a frameless mirror perpendicular to the photograph of a nude and, whilst maintaining the mirror at a 90° angle, you turn it so that the symmetrical halves of the image steadily contract or expand. The whole develops constantly, in bubbles, elastic skins, that as they expand, leave the rather theoretical slot of the axis of symmetry. […] Faced with this abominably natural event that monopolises ones attention, the question of the reality or virtual nature of the two halves of this evolving whole fades in the consciousness, disappearing on the frontiers of memory.12

In this example, we can clearly see that what creates desire is not the object that is portrayed but indeed the portrayal itself, even though it is very far from reality. Bellmer’s main theory was that the subconscious makes associations between the different parts of the body, and that therefore any image of the body is potentially a sexual image. The legs prefigure the groin, the arm heralds the penis, the stretched neck and head thrown backwards prefigure both the end of the penis and the involuntary gestures during orgasm, etc. In a most exemplary fashion, erotic photographs bring into play what is off camera, and it is also that which is off camera that is desirable. There are many examples of erotic photographs where the sexual content does not sabotage their aesthetic force, but, on the contrary, complements it.

For Barthes, either we look at photographs distractedly or we focus on them to such an extent that we risk losing our minds. The distraction offered by erotic photographs is a way of touching upon the reality of desire without fully succumbing to it. Yes, erotic photography offers a distraction, but that only happens so that the spectator can then actually look and understand the significance of desire in the relationship to a work of art. In this, it is time to restore erotic photography to the same standing as its fellows.

Camille Moreau

1 Georges Bataille, L’érotisme (1957), Paris, Éditions de minuit, 2011, p. 156.

2 Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Paris, Seuil, 1980, pp. 92-93.

3 Paul Sztulman and Dork Zabunyan, Politiques de la distraction, Paris, Les Presses du Réel, 2021, introduction (non paginé).

4 Patrick Baudry, La pornographie et ses images (1997), Paris, Pocket, 2019, p. 203.

5 Ibid. p. 214

6 « La distraction est plus profondément une attention désirante » Paul Sztulman and Dork Zabunyan, Politiques de la distraction, Paris, Les Presses du Réel, 2021, introduction (non paginated).

7 Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Paris, Seuil, 1980, 32 (emphasis added).

8 Emmanuel Hocquard, Méditations photographiques sur l’idée simple de nudité, Paris, P.O.L, 2009, p. 20.

9 RIEGL, Aloïs, Grammaire Historique des Arts Plastiques [1899], translated from German to French by Éliane Kaufholz, Paris, Editions Klincksieck, 1978, p. 121.

10 Aloïs Riegl, Grammaire Historique des Arts Plastiques [1899], translated from German to French by Éliane Kaufholz, Paris, Editions Klincksieck, 1978, p. 121 (emphasis added).

11 Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Paris, Seuil, 1980, pp. 126-127.

12 Hans Bellmer, Petite Anatomie de l’Image (1957), Paris, Allia, 2016, p. 25.