No image is truly unequivocal, and none can be taken for a message to be communicated, devoid of traces. Even in the case of an advertisement seeking out optimal commercial effectiveness, even in a propaganda film attempting to shape minds once and for all, an image seeps out everywhere, providing a glimpse of the conditions of its production or the position it assigns to spectators, at times through the smallest of details. Among the tasks of the art of image is to make perceptible this detail lying in a visual trace, to be alert to these “labile signs of which [images] are the keepers”—images described by Sylvie Lindeperg as “less a reflection of a historical event than its witness and the bearer of its coordinates” (La Voie des images, 2013).

In his work as a filmmaker, Harun Farocki has continuously followed these “labile signs” that gravitate and swarm within images, from those belonging to the pantheon of cinema to those of an audiovisual production that is not necessarily artistic. The paradoxical condition of the attention brought to these visual signs arises from a floating gaze, not so much superficial or overhanging as wandering along the image’s surface to probe into the potentiality of meanings. The incidental detail seized upon through distracted observation is, for instance, what Harun Farocki experiences in watching the American army’s “serious games”—those videogame-inspired “games” that the US military uses to help soldiers returning home from war zones recover from post-traumatic stress disorder.

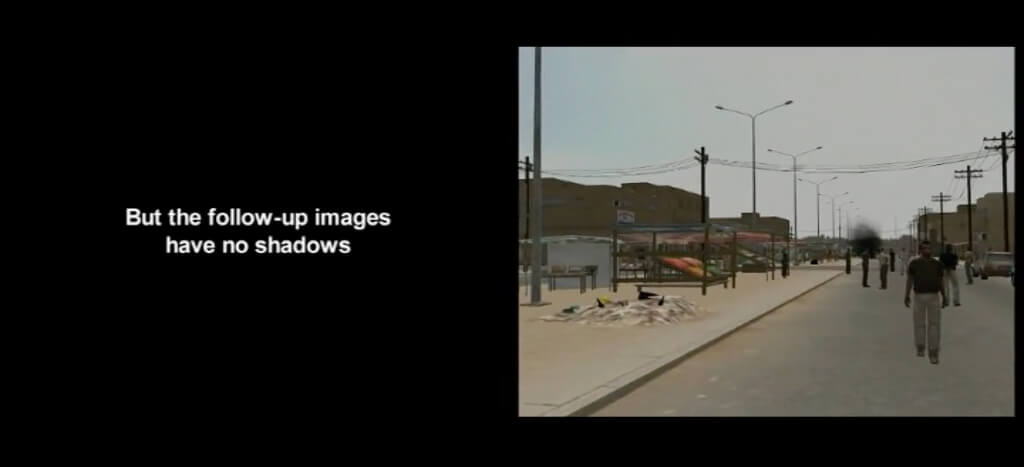

In the fourth of his Serious Games, Farocki notes that the figures portrayed in their digital environment—a Baghdad neighborhood under a scorching sun just after a bombing—have no shadow, which is a visual aberration. But this aberration, caught by Farocki during a viewing (or in fact, a re-viewing) of this audiovisual document from the US army, leads the filmmaker to grow aware of the following reality: the images used to help soldiers recover are less sophisticated than the images used to help them train for war. In addition to the “asymmetrical war” between Americans and Iraqis, there is a further asymmetry: that among images, as those intended to help recovery are “poorer” than those intended for combat (in which armed vehicles do indeed cast a shadow).

A simple detail—a missing shadow—thus leads Farocki to pursue the act of taking the visual and sound universe of video games seriously, as, far from mere entertainment for half-wits, gaming has become, in the filmmaker’s words, “the single most important medium to shape collective imagination” (Trafic no. 78, summer 2011). For this reason alone, it is worth taking time to examine it a bit more closely, and consider the ways in which it is used beyond the entertainment industry. A distracted perception, which here refers to a lack in the image, is thus able to transform our appreciation of a form of popular culture that it is no longer appropriate to deem “lowbrow”. Likewise, it allows us to recreate an entire historical context—that of the Iraq War and its transnational aftershocks—using a transformed gaze that comes upon new “coordinates” of the event. An experience of distraction may then, in its own way, upend preconceived notions of a medium (videogames), and draw our attention to the worlds that it constructs and the stories it recounts, for better or worse.

Dork Zabunyan