One would hardly imagine that the repatriation of ill-gotten artifacts is a simple affair, but it’s striking and dismaying to behold the complexity and fragmentation of the legal and political frameworks involved. In this overview by Andrew Meyer, a PhD candidate at EHESS and lecturer of sociocultural anthropology at the American University of Paris, we visit the world of art fairs and auctions involving indigenous objects and begin to see the range of stakeholders with different and often conflicting agendas, the diversity of things that have been uprooted from their ceremonial and practical uses, and the efforts underway to untangle this byzantine economy.

— Daniel Levin Becker

Hôtel Drouot, Paris, December 2014. An auction is about to begin and tensions are high. Among the attendees, besides the usual collectors, dealers, and auction-house employees, are a dozen journalists, a U.S. embassy representative, the director of the Indigenous rights NGO Survival International, a French lawyer, and members of a Parisian solidarity organization. This is the fourth auction in Paris since April 2013 being contested by sovereign Native Nations1 for the sale of ritual objects including Hopi Katsina Friends—the faces of rain-bringing deities—and a delegation of emissaries from the Navajo Nation has flown in from Arizona to recuperate Jish, sacred objects used in curing rituals, in order to bring them back to their homelands. Pleas by the Hopi tribal government and Survival International to remove the sacred beings from sales have been dismissed three times by French courts in favor of auction houses. Fed up with the costly legal proceedings and bad press, today’s auctioneer lets the room know he is in control. As the bidding begins, two activists are dragged out by security guards for showing “propaganda” to journalists. Later, the Survival International representative places a winning bid of €5,500 for a Katsina Friend, which he plans to repatriate to Hopiland on behalf of a French anthropologist, only to be ridiculed by the auctioneer.

Since this auction, my first when I began my fieldwork in France, I have attended twenty-five art fairs and fifteen in-person auctions containing items subject to repatriation claims in Paris and the United States. Since 2019, I have also reviewed over six hundred online sales and sixty-five thousand lots of Native American and Native Hawaiian objects in my capacity as a researcher for the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA).2 While auctions can be exciting and entertaining spaces to bid on art and collectibles, they often also reproduce vestiges of colonial violence as irreplaceable cultural heritage is sold off and Indigenous Peoples are disregarded and excluded. Each year, hundreds of sales worldwide offer thousands of objects that Native Nations may wish to repatriate.

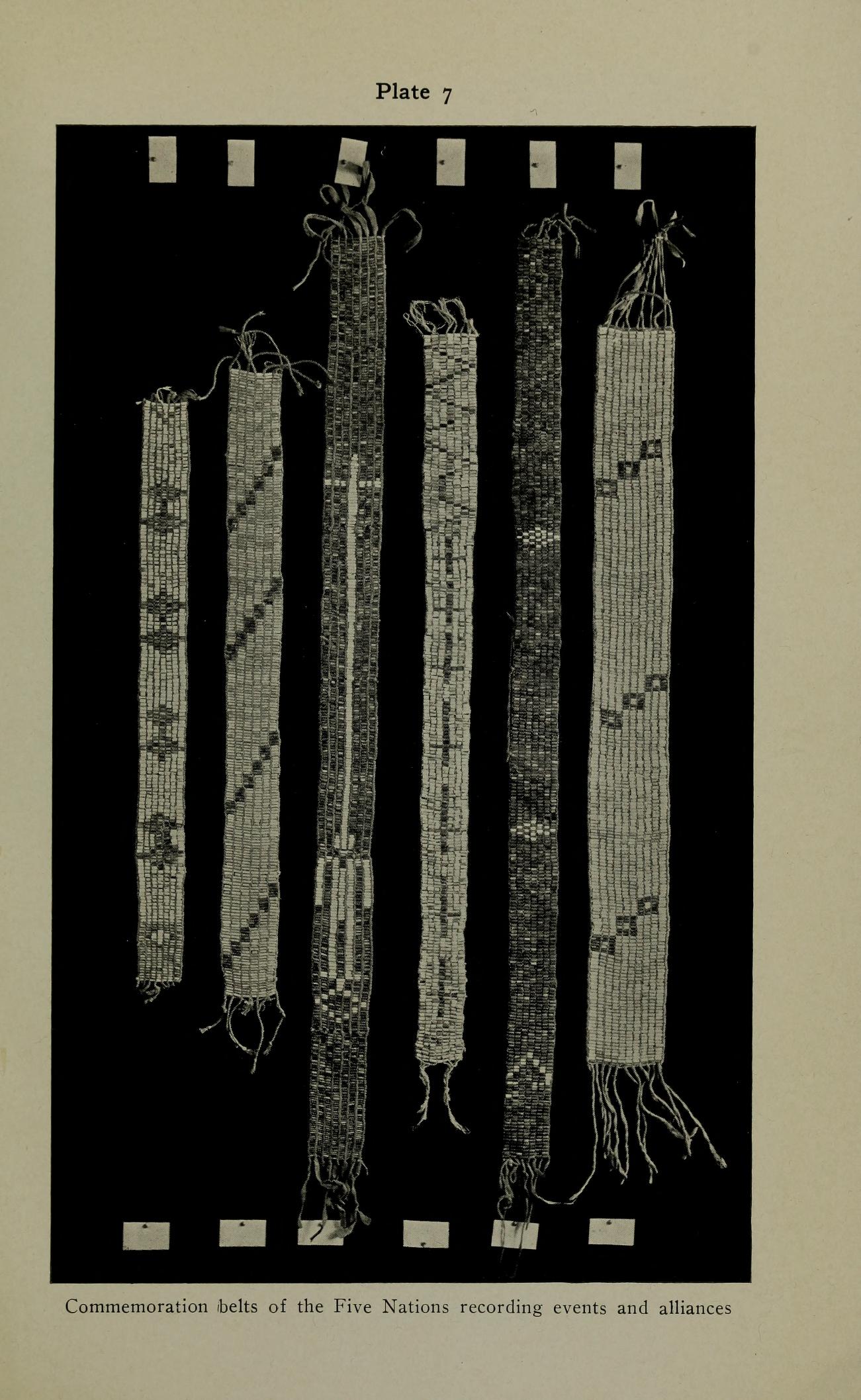

Since the 1970s, tribal representatives have been attempting to recover from auctions objects of cultural and religious significance such as wampum belts, masks, rattles, pipes, medicine bundles, funerary items, and human remains. These are not mere sources of nationalistic pride, as the objects of many restitution claims around the world are; indeed, they are extremely important to the continuation of Indigenous traditions, often considered family members or living beings with spiritual, even dangerous powers. Because they are used in their true cultural and ritual contexts to ensure rain, sustenance, fertility, and general health, their proper respect and stewardship are vital to both the survival of cultural practices and the physical and emotional well-being of Native Nations. In the case of Ancestors and their grave goods, their excavation is profoundly disrespectful and detrimental, not only to the afterlives of the Ancestors themselves but also to the descendants tirelessly trying to heal the wounds caused by centuries of colonial dispossession, displacement, assimilation, and violence—by putting them back in the ground where they belong.

Although many of these objects were stolen, confiscated, looted, or excavated from graves and acquired under duress, or otherwise obtained in violation of tribal customs and laws, individual tribal members have often been coerced into selling them out of economic necessity due to squalid reservation conditions. Still, not all of the objects in question are protected by federal or state laws. The AAIA, founded in 1922, has long been active in restitution efforts (among many other forms of advocacy). It played an instrumental role in the passing of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA), though this legislation rarely covers collections existing outside the U.S., and does not protect sacred objects in the marketplace if there is no proof of illegal trafficking from a museum or from federal and tribal lands after 1990. In 2016, after a sacred shield from the Acoma Pueblo stolen in the 1970s was taken off a Parisian auction block without any legal recourse for repatriation, the Association joined the Pueblo to advocate for a law explicitly banning the exportation of ritual objects, forging a path for a potential UNESCO treaty between France and the U.S., the Safeguarding Tribal Objects of Patrimony (STOP) Act. The shield was voluntarily repatriated to Acoma four years later by the American dealer who had consigned it to the Parisian auction house,3 and the STOP Act was signed into law in December 2022.

In the meantime, the AAIA began tracking auctions in 2018 and asked me the following year to help monitor sales and prepare alerts to circulate to Native Nations across the continent. I find upcoming auctions online, sift through their catalogs for problematic items, make a list of tribal affiliations and geographical provenances mentioned in the sale, and provide contact information for the auction house. The Association then distributes the alert by email to hundreds of Indigenous representatives, who can determine whether they wish to request that an item be removed from sale so it may be repatriated and reused in ceremonies, placed in safekeeping, buried, burned, left to the elements, or shared, if appropriate, in a tribal museum.

Tribes’ first option is to engage diplomatically with the auction house and try to convince the consignor to voluntarily repatriate the items free of charge. Auction houses have generally been dismissive of these pleas, though some U.S. firms have begun to facilitate the return of high-profile objects. For example, despite its past lack of cooperation with Indigenous representatives and the AAIA, Cowan’s Auctions in Cincinnati took the initiative to repatriate a Ahayu:da (war god) to the Zuni Pueblo in 2020.4 Another strategy is to prompt law enforcement intervention; each auction alert contains contact information for federal agents who may be able to help recuperate objects for tribal representatives. However, the burden of proof is placed not on the consignor and auction house to consult with Native Nations and prove good title, but on tribal governments to show that an object was acquired or is being sold illicitly—so it’s rare that law enforcement can intervene. Without cooperation from auction houses and consignors, or the realistic threat of legal action, some tribes have had success appealing to or praying for wealthy benevolent bidders to purchase objects on their behalf. Indigenous Nations can also bid on items with their own funds, though many tribes cannot afford to purchase items at auction, while other Nations refuse to contribute to the commodification of sacred objects.

Compiling these auction alerts can be disturbing, since my research often turns up powerful sacred objects, clothing taken from graves or massacre sites, and even human remains. I have come across several of the latter: a scalp, bones, objects containing human hair. While an AAIA employee and I were reviewing a large sale in Ohio in 2021, we were shocked to encounter an “Indian scalp,” mounted in a picture frame, consisting of a braid attached to a “hide.” As an Indigenous woman who has worked in repatriation for many years, this colleague still finds it very spiritually taxing to see such things. The Association’s executive director later told me that she prefers that a non-Indigenous person like myself review auctions so she doesn’t have to see Ancestors in a way that violates of her religious beliefs. But I couldn’t help sensing that it was dangerous and disrespectful for me even to lay eyes on this Ancestor—similar to my feeling upon witnessing Hopi Katsina Friends on display at that first auction in Paris. (Since the sale of Native human remains is illegal according to NAGPRA, the AAIA contacted the FBI and the scalp was removed from the Ohio auction catalog.)

While Indigenous Nations attempt to remove sacred objects and ancestors from public view and commercial circulation, some of these items are considered contaminated and must be ritually purified before they can be reintegrated—or not—into ceremonies. The contamination is both spiritual and literal: they may have been cursed or disrespected, but also treated with toxic pesticides. Some tribes will not even accept the repatriation of tainted objects or ancestral remains for religious and health reasons. Other Nations that have no historical rituals for purification or reburial, have created new ones to perpetuate these living religions.

Auctions containing problematic objects occur almost every day. It’s difficult for the AAIA and Native Nations, with their limited resources, to keep up with them all, but they are doing their best to challenge the sale of their cultural heritage. Whether using the aforementioned strategies or leading public education and media campaigns,5 their goal is the same: to prompt collectors and auction houses to one day consult with Indigenous Peoples before buying and selling items acquired under unethical circumstances or in violation their religious beliefs.

Andrew Meyer

Case Study Examples

In 1978, the Zuni Pueblo contested an auction in Santa Fe that contained an ancient Puebloan “mummy” taken from a cliff dwelling on the Navajo Nation. They invoked a New Mexico statute prohibiting the sale of human bodies, then buried the Ancestor in a cemetery. The same year, Zuni leaders challenged a Sotheby’s sale in New York containing a Ahayu:da—a wooden carving of the War Gods, typically left as an offering at a shrine and meant to decompose. After the Pueblo hired lawyers to argue that it was stolen tribal property, it was confiscated by the FBI. To avoid legal proceedings, the consignor agreed to cede the Ahayu:da to the tribe. 6

A ceremonial headdress from the Kwakwaka’wakw people of British Columbia was confiscated by the Canadian government in 1921 due to a ban on Indigenous religious practices. It then became part of the Museum of the American Indian in New York. In the 1960s, the headdress was sold to André Breton, who displayed it in his Parisian atelier until his daughter planned to sell his collection at auction in 2003. Instead of being preempted by the Louvre, the heiress was convinced to voluntarily repatriate it to the U’Mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, British Columbia.7

1 There are 574 Indigenous Nations in what is now the United States whose inherent sovereignty is recognized by the colonial government. They all have their own governments and many have legal jurisdiction over territories and citizenship. About four hundred other tribes are unrecognized by the U.S., including many Native Hawaiian organizations representing the interests of the Kānaka Maoli.

2 The AAIA is a U.S.-based NGO led by an all-Indigenous board and executive.

3 BUCKLEY Elena Saavedra 2020, “Unraveling the mystery of a stolen ceremonial shield,” High Country News, August 1, 2020. [Online] Accessed on April 5, 2023

4 SURFACE Tom 2020, « ATADA Helps Return Sacred War God Artifact to the Zuni Tribe », The Indian Trader, vol. 51, n°11 (novembre 2020), p. 8-9

5 TABACHNIK Sam 2023, “A Denver collector’s Native American artifacts are up for sale. A tribal group says these cultural objects need to be returned,” The Denver Post, March 18, 2023. [Online] Accessed on May 17, 2023 ; STROMBERG Matt 2022, “Why Is an Auction House Selling Works by Imprisoned Native Artists?,” https://hyperallergic.com/773455/bonhams-selling-works-by-imprisoned-native-artists/ consulté le 17 mai 2023

6 MERRILL William L., LADD Edmund J. & FERGUSON T.J. 1993, “The Return of the Ahayu:da : Lessons for Repatriation from Zuni Pueblo and the Smithsonian Institution,” Current Anthropology, vol. 34, no. 5 (December, 1993), pp. 523-567, p. 536

7 MAUZÉ Marie 2008, “Trois destinées, un destin. Biographie d’une coiffure kwakwaka’wakw,” Gradhiva: revue d’histoire et d’archives de l’anthropologie, Musée du quai Branly, no. 7 (n.s.), pp. 100-119