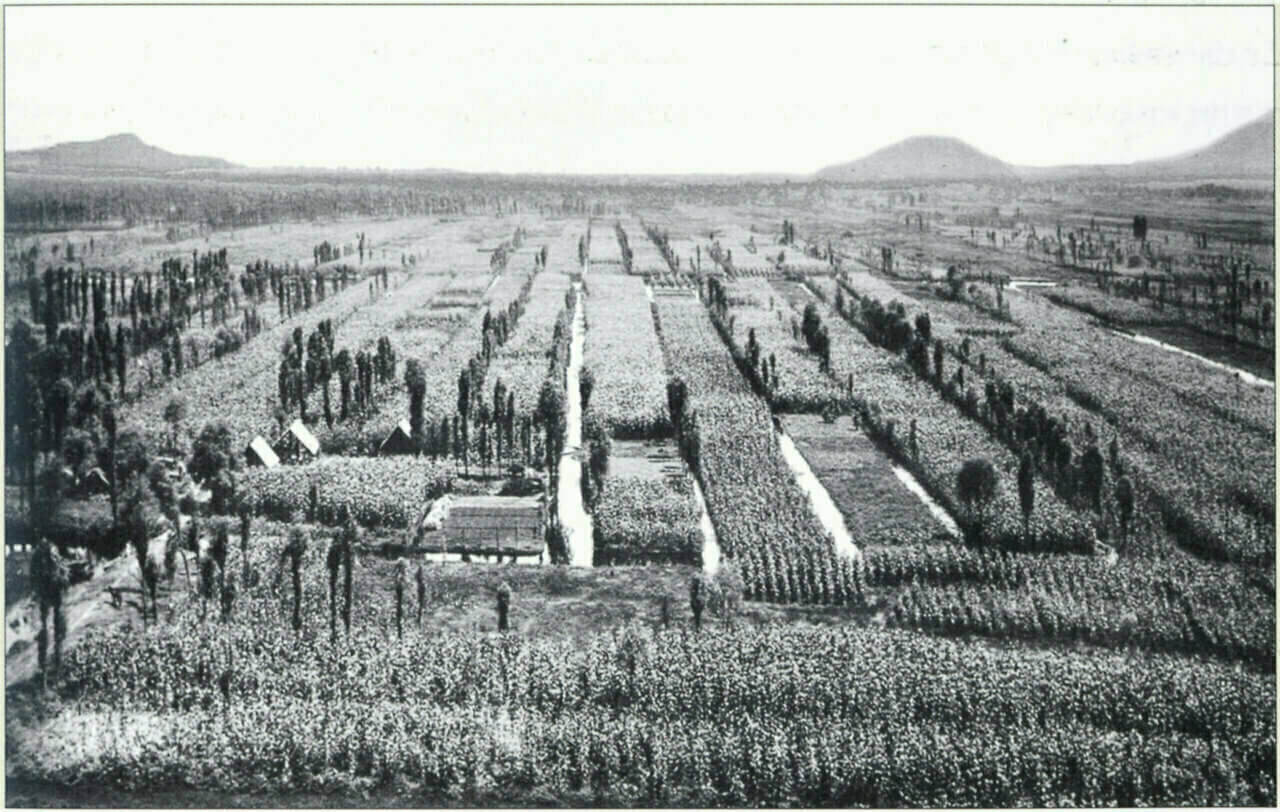

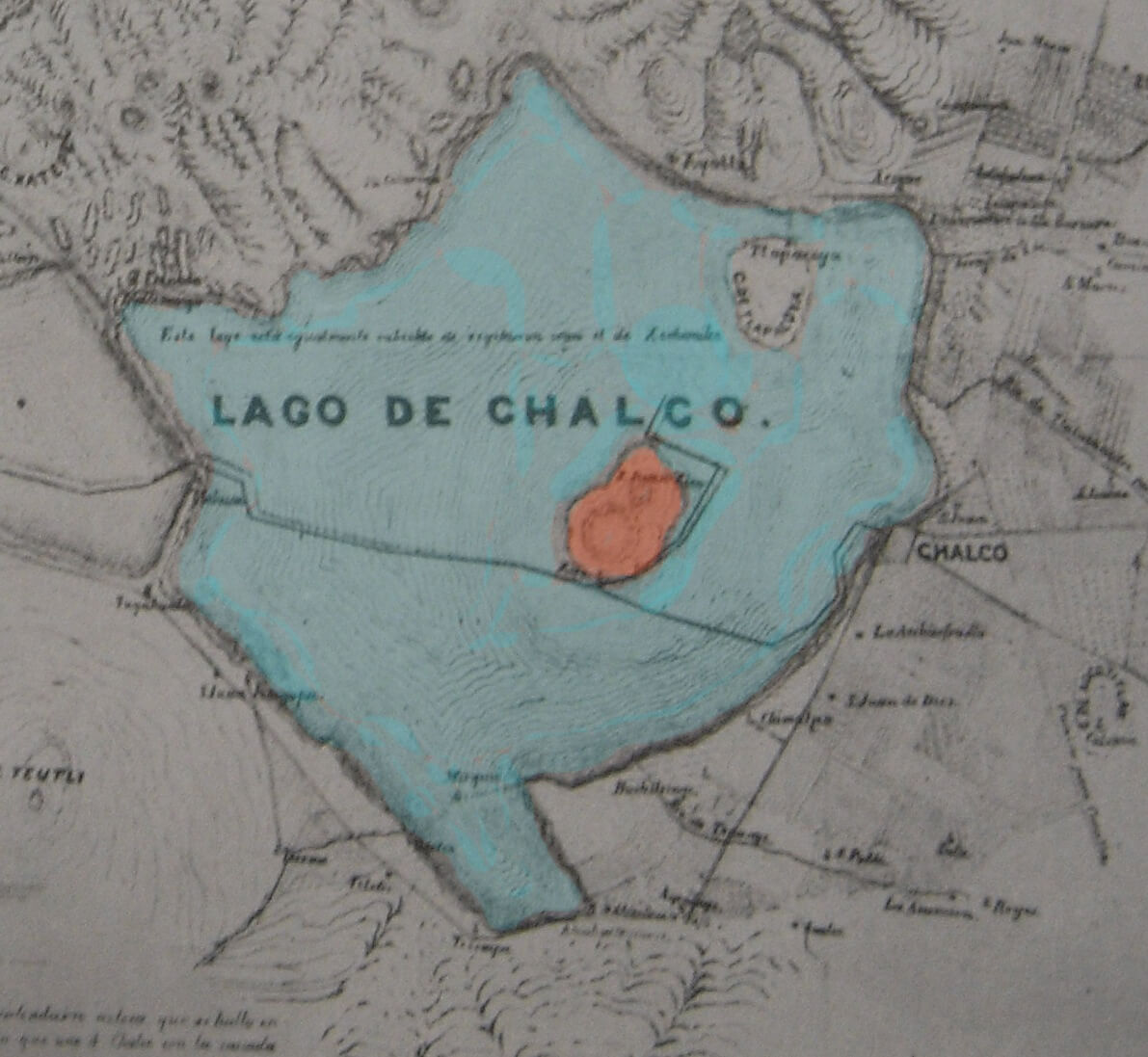

Before the invasion Xico had been an island in the midst of Lake Chalco in what is now the State of Mexico.

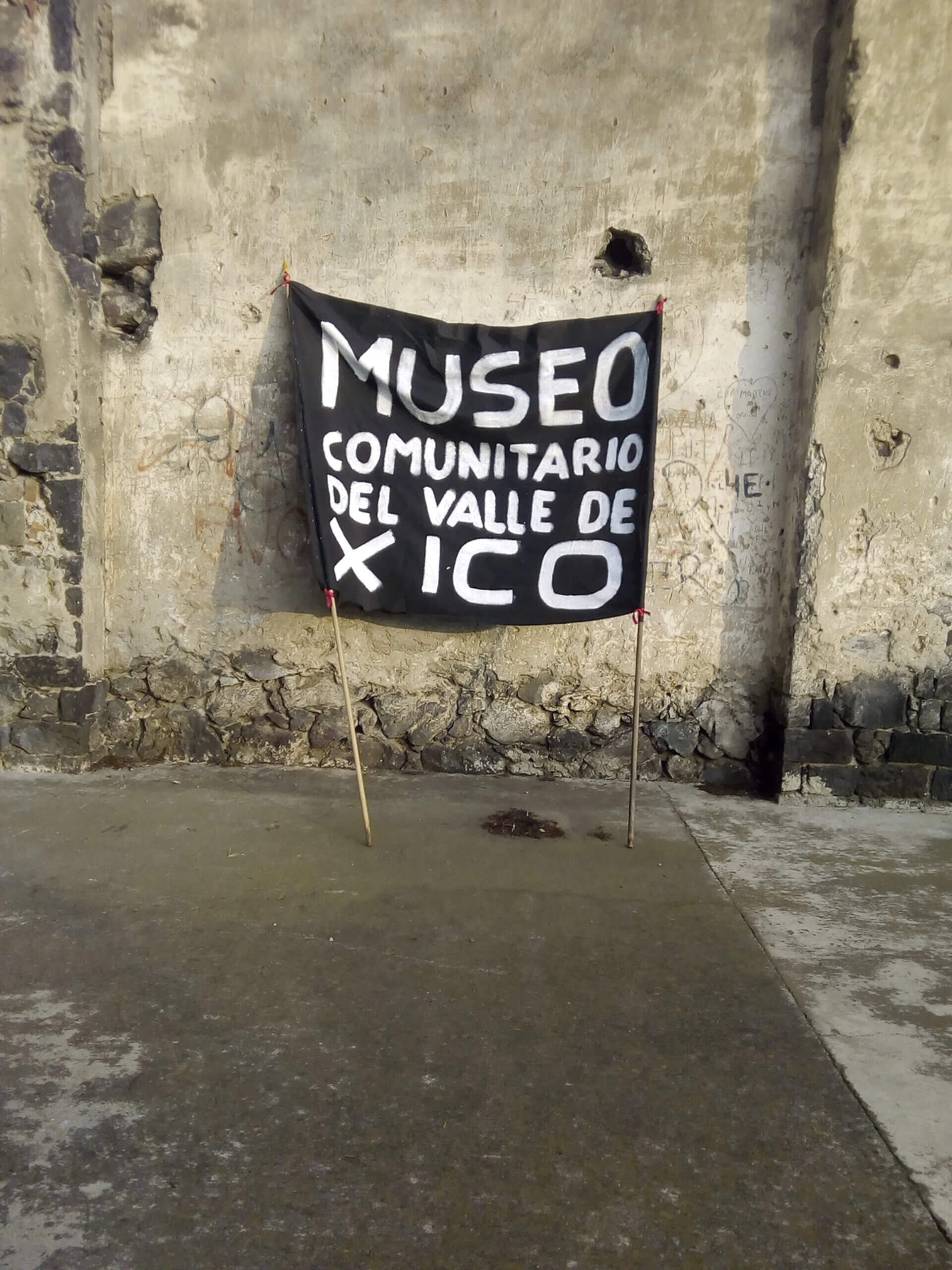

“The Valle de Xico Community Museum is a project which came into being as an initiative by members of a community to rescue, to know, to study, present and preserve the cultural heritage and ecology of a community.”

The community museum cares for the land, the more than human, Indigenous culture, and the cyclical use of water. In a colonial country, as are all countries of the Americas, this results in active and daily repression by the state and non-indigenous society.

The Museum views as its priority:

To carry out community work based on support for self-initiated local projects

Participation in National Movements

Involvement of the Community in the solution of Social Problems

Recovering the environment with the return of the lake

Recovering historical memory

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Tlaloc is the deity of water, lighting, rain, agriculture and thus, fertility.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Xico means navel – the center – in the Indigenous language of Nahuatl. Xico, as you can see in the drawing, is surrounded by the neighboring beings of water and mountains.

Lake Chalco and its neighboring Lake Xochimilco produced 20 million tons of maize annually on indigenously engineered chinampas (floating island gardens), which was transported to Tenochitlan (modern-day Mexico City). Back then, it was the Mexica capital, with a population of 200,000 people in the early 15th century (Paris had 100,000 inhabitants at that time). This was all before the invasion that would cause the immediate death of 90% of all during the life of the invader – Cortes. And 400 years later, by the eve of the Mexican revolution in 1910, 99% of the land was owned by the non-indigenous.

Lake Chalco was part of five lakes interconnected with each other, forming one system. The lakes were managed to prevent flooding and still allow for agriculture even during the dry season. The systematic destruction of the water system began immediately after the conquest of Mexico. All five lakes began to have their water removed.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Huehueteotl is the deity of fire, thus the creator of life.

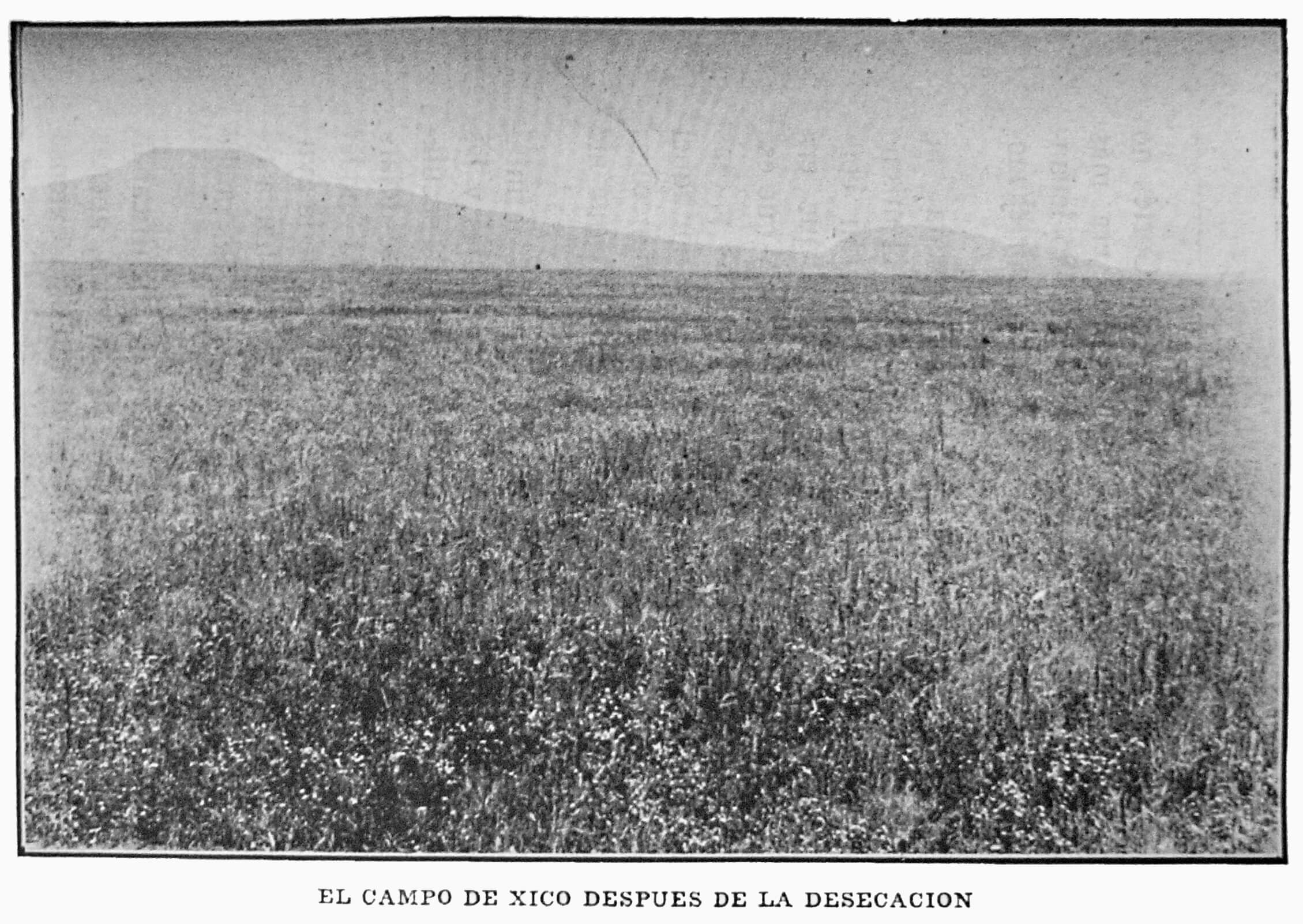

What had been the lake became private farm and ranch property.

At the turn of the 20th century, the water that remained in Lake Chalco was totally drained away by a Spanish colonizer from Colombres in Asturias, Spain, who bought the island but not the lake, which had been communal. This resulted in the destruction of, or severely affected, 23 towns and communities and destroyed the economic base of the people of the land, leaving consequences that would last forever for the water, the land, the more than human and humans.

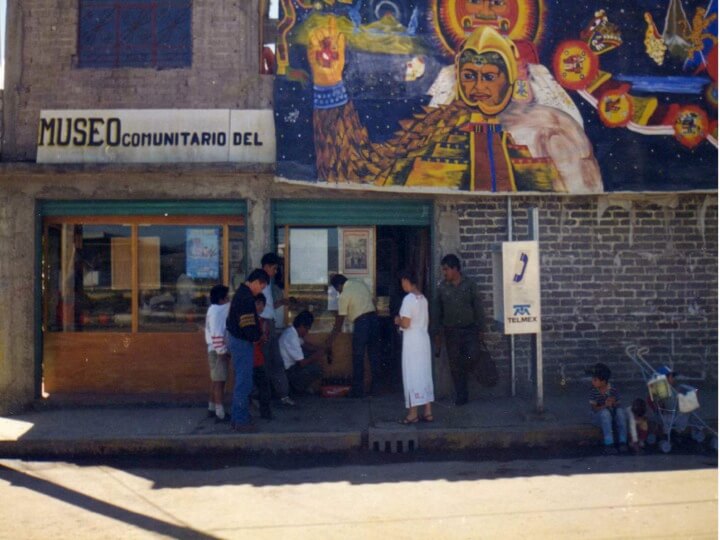

The Community Museum opened in 1996 and two truckloads of soldiers arrived and threatened to close the museum. Indigenous culture is still considered a dangerous activity in colonial America. There is no post-colonization in the Americas.

The removal of the water from the aquifer caused the entire area to sink. The dry lakebed also began to sink. A depression was formed and rainwater began to collect. After some time, a new lake came into being, now named Lake Tláhuac-Xico.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

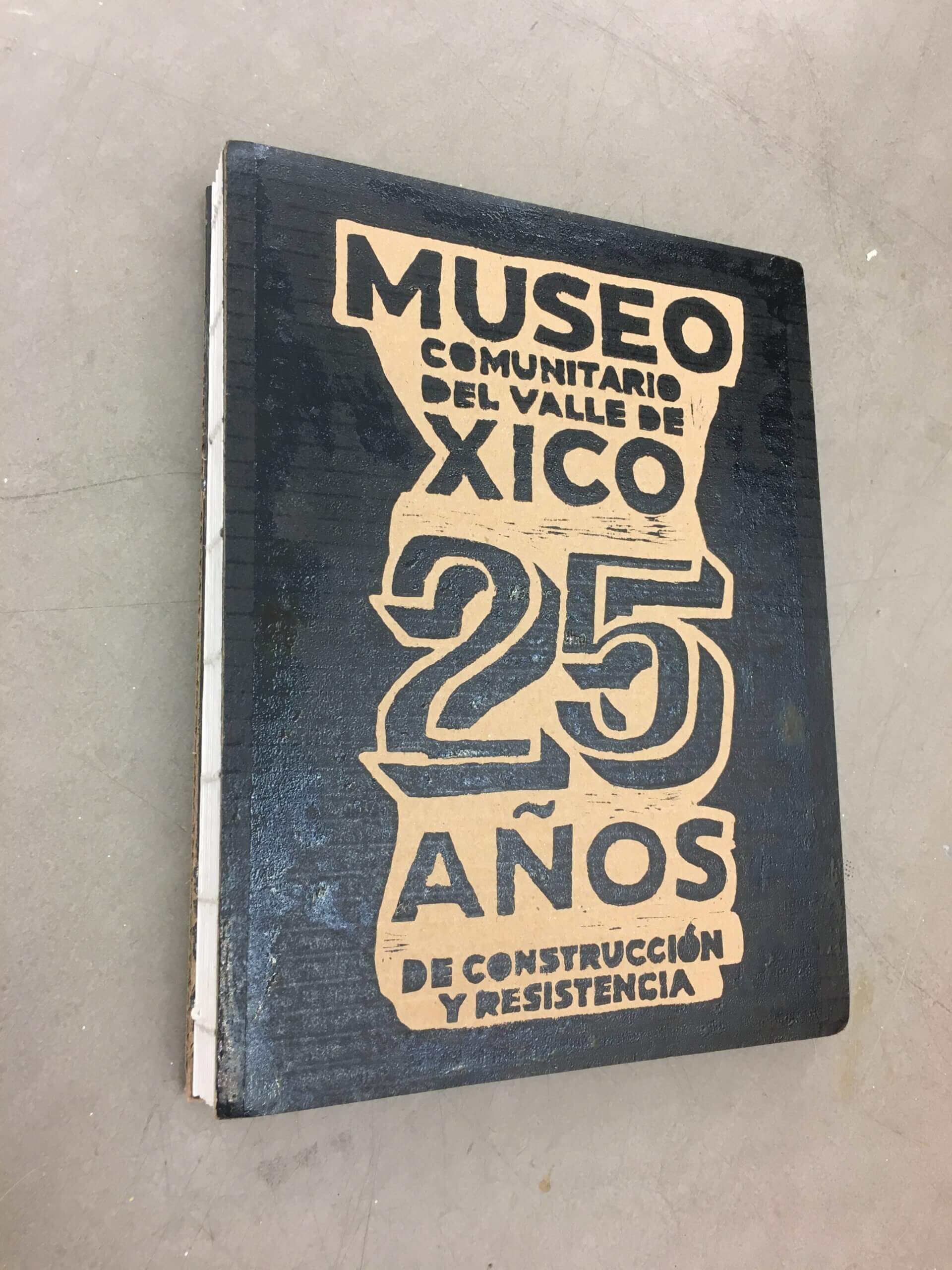

This year, the Community Museum produced a publication celebrating its 25 years of making and resistance.

Without financial support from the government, but facing threats and intimidation, the Community Museum was able to save almost 5,000 pre-invasion Mesoamerican artifacts from oblivion or destruction, since there was no other institution in the municipality interested in protecting this cultural heritage.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

These artifacts were donated to the museum by members of the local community, who found them in the surrounding area. It is these people, from the community, who have until today resisted the elimination of the social and cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples, without which we would only be a pathetic lover of Europe, in Jimmie Durham’s words.

This was the museum in 2009 when I first met Genaro Amaro Altamirano, the chronicler of Xico and cofounder of the museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

This is an artefact found by a construction worker who brought it to the museum and as a consequence lost his job.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Household deities.

I was invited to make a new work for dOCUMENTA (13): the installation The Return of a Lake is based on the aesthetics of the Community Museum, with a maquette of the lake greeting visitors as they came in, allowing them to place themselves in context with the environment.

The community requested a book telling their history. This is also an element of Return of a Lake, along with a special edition in leather, gold and amate paper, and a copy was hand-delivered to the director and founder of the Museum of Emigration in Colombres, Asturias in Spain, which continues to celebrate the ecocide of Lake Chalco and the Spanish colonizer who was born in this town and committed this act.

Sales from this publication support the Community Museum.

Periodically, security forces threaten Genaro de Amaro Altamirano, who is considered by the local government to be the greatest threat in this destitute and violent region for his work in support of Indigenous culture and for the cyclical use of water. On August 5, 2010, 24 police officers with bulletproof vests and weapons arrived at the museum to arrest Altamirano. Colonization continues daily in the Americas.

Quetzalcoatl, the shining being, the feathered serpent – deity of air, of wind, of knowledge, of writing, books, art, music, and dance. His blood gave birth to people. He is also the lord of the star of dawn – greeting us for the glory of a new day, and today, he resides in Xico.

Quetzalcoatl, the shining being, the feathered serpent – deity of air, of wind, of knowledge, of writing, books, art, music, and dance. His blood gave birth to people. He is also the lord of the star of dawn – greeting us for the glory of a new day, and today, he resides in Xico.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum

As renovated work was carried out in the building which housed the museum, they continued to work from an abandoned stable. The museum was able to reopen in 2018.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum

The Sky Beholder, responsible for following the path of celestial bodies.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum

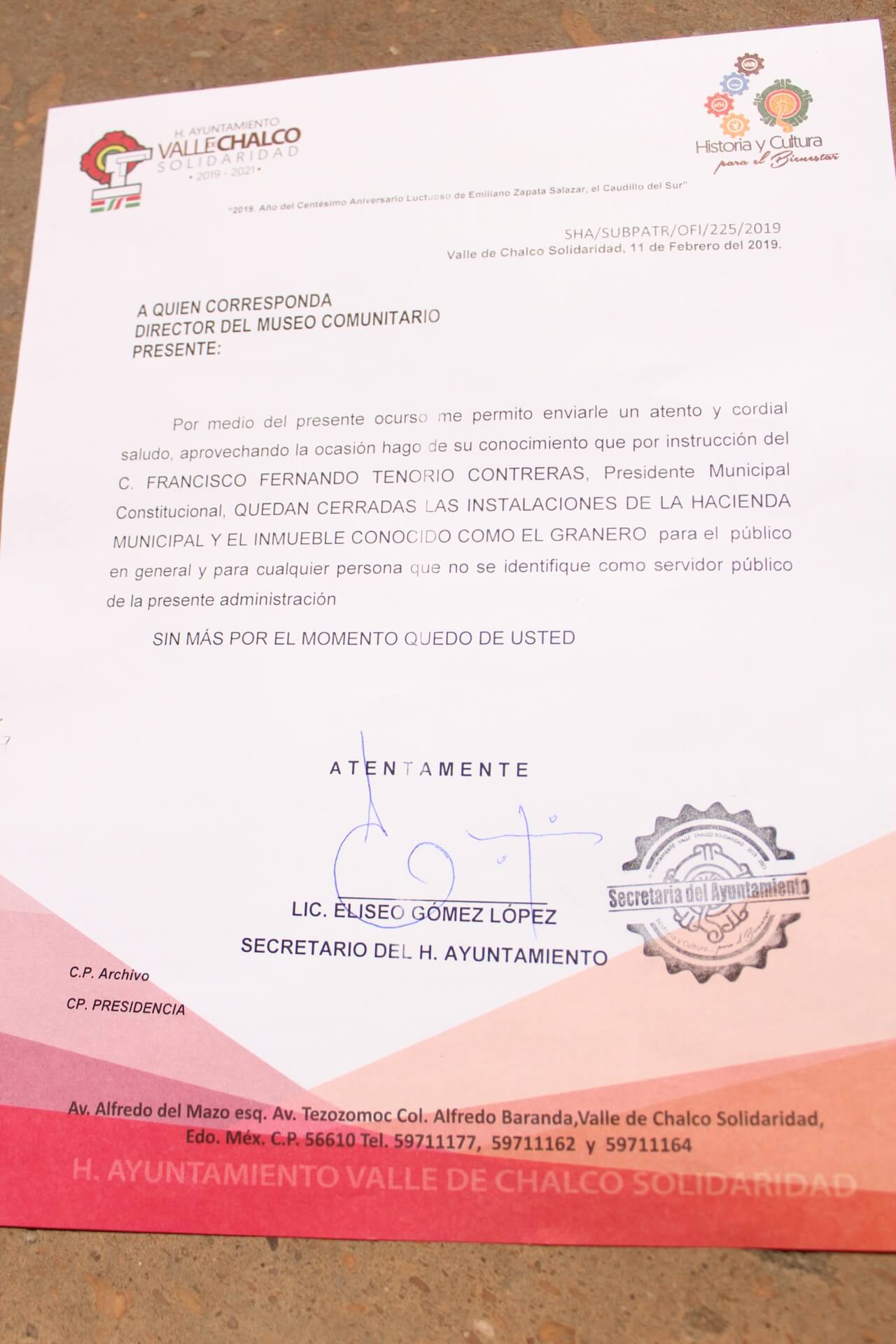

In 2019, the municipality of the Valle de Chalco sent a letter closing the museum – with no explanation. That is colonization.

There are twelve police officers in this image, guarding the entrance of the museum to prevent the people of the community from visiting their own museum. The community has no access to their own art and culture. It is the community that has found these artifacts. The youth no longer have a museum where they can meet, discuss and make art.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum

The museum built a shed just in front of their closed museum and this is where the museum now meets but it is difficult when it rains and is cold. The community protests. The banner says, Tenorio (the mayor of the time who ordered the closure for no reason), the artifacts do not belong to you but to the people.

The community protests. The banner says, Tenorio (the mayor of the time who ordered the closure for no reason), the artifacts do not belong to you but to the people.

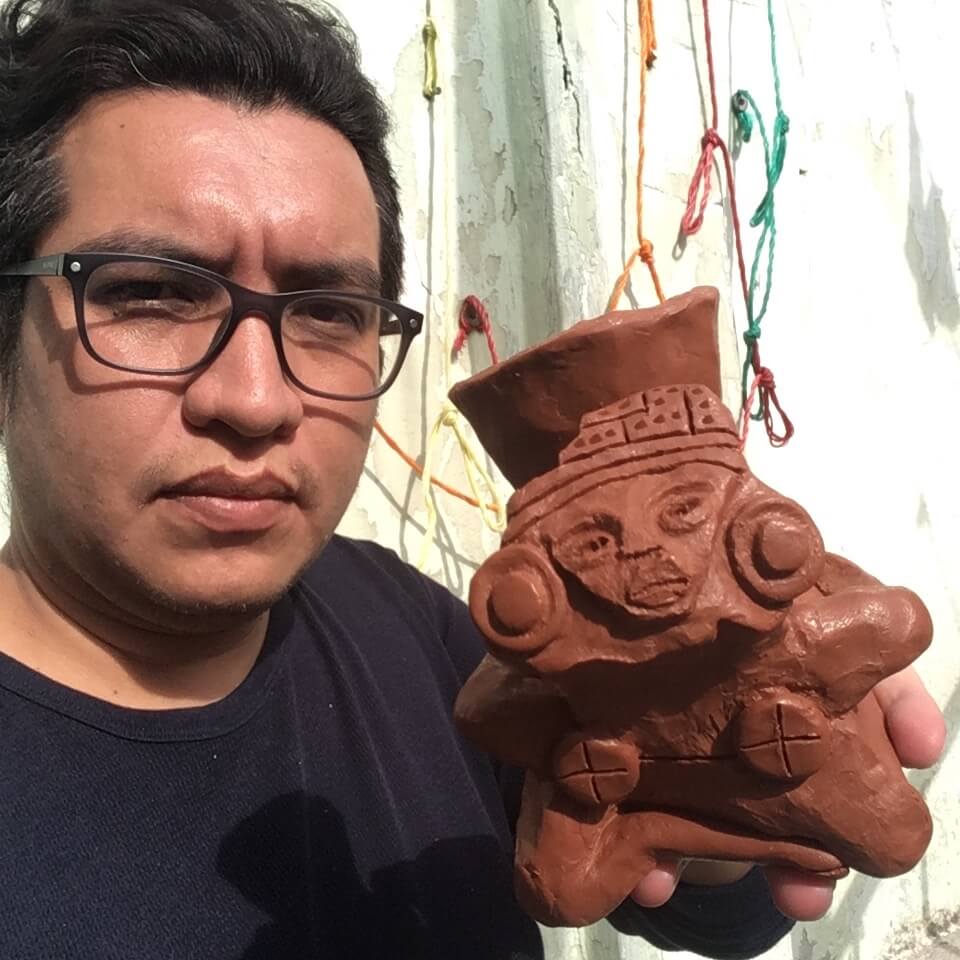

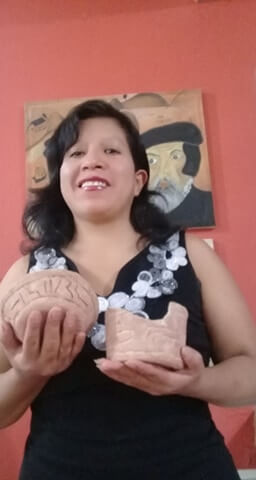

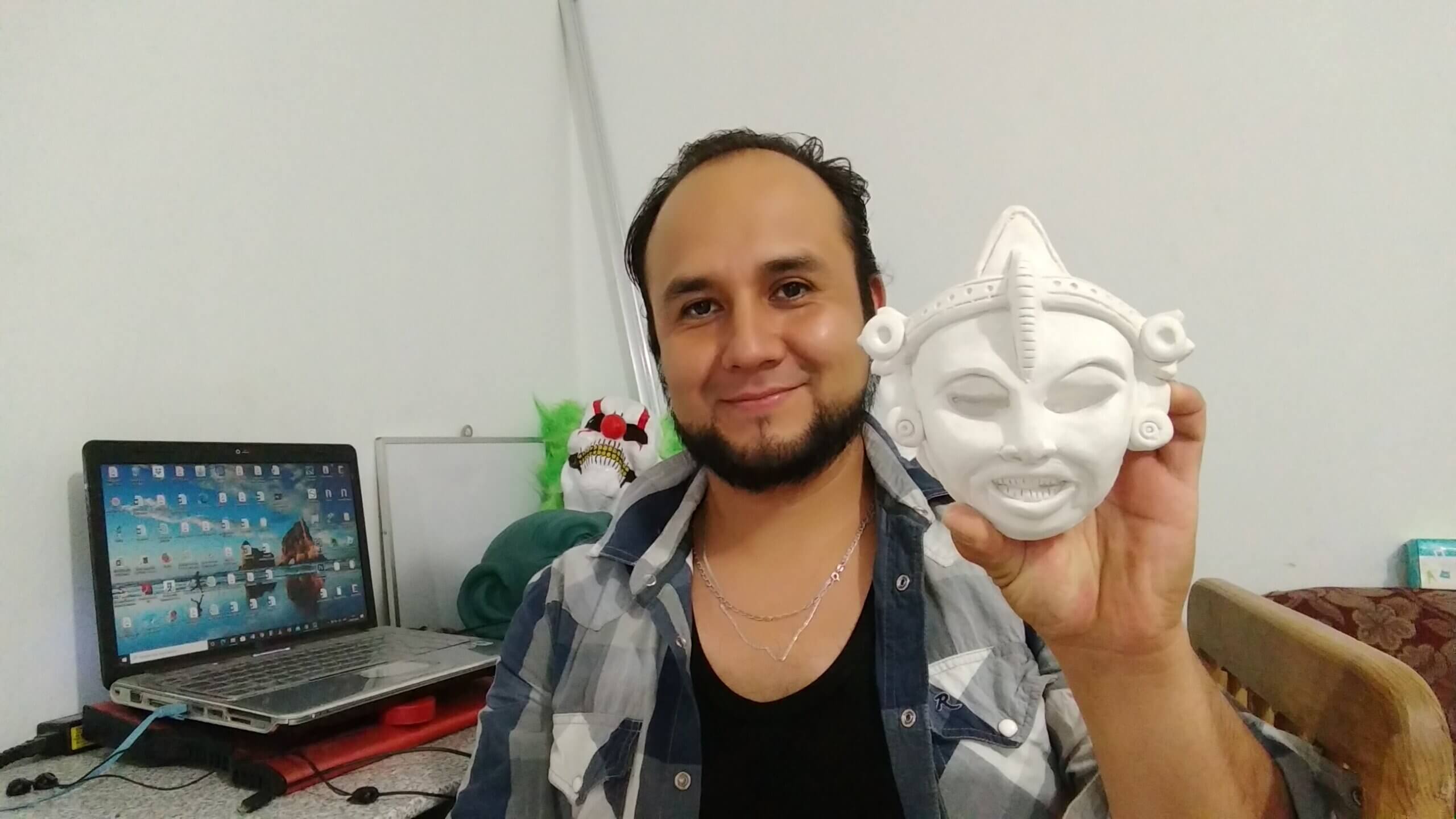

During the first lockdown, I began to learn to make ceramics and decided to study the works in the museum’s collection. I began to recreate artworks that are no longer available to the community.

Son del Pueblo/Of the people is the result and those who read this are all asked to participate if you like.

Of The People Participants

You are invited to make a ceramic work (it does not need to be fired) based on artifacts from the museum. There is a pdf on my website with images of the museum’s collection: http://www.mariatherezaalves.org/assets/files/son-del_pueblo_25_webversion.pdf

Or perhaps organize a workshop with a few friends. Take a picture with the ceramic and send it along with your name and the city where you live to studio@mariatherezaalves.org and to the museum at museocomunitariodexico@gmail.com and it will be placed on their website. And perhaps one day we can gather the ceramics made by all of us and have a temporary Valle de Xico Community Museum in different places around the world.

This work is an attempt to make visible to the municipal authorities the importance of the museum and its collection to the community and to others – like us. It is an attempt to convince the municipal authorities to return the art of the community to the community.

Chiedza, Toronto, Canada

Hamza, Basel, Switzerland

Valentina, Naples, Italy

Stephany, Xico, Mexico

Neri, Valle de Chalco, Mexico

Ana and Philipp, Berlin, Germany

Lara, Coruña, Spain

Vera, Sorocaba, Brazil

Alva, New York, USA

Joen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Sonia, Valle de Chalco, Mexico

Lesli, Xico, Mexico

Farah, London, UK

Jesús, Xico, Mexico

Noa, Coruña, Spain

Sofia, Valle de Chalco, Mexico

Marcela, Berlin, Germany

Noara, London, UK

Yair, Xico, Mexico

Utsa, New York, USA

Alessandro, Caserta, Italy

Azaria, Chalco Solidaridad, Mexico

Collettivo Damp, Naples, Italy

Dina, Berlin, Germany

Leonardo, Xico, Mexico

Tyra, Viola, Ingmar, Simone, Kirsten

Magnus, Malmo, Sweden

Carla, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Julia, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Eva, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Gabjia, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Jabe, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Juliette, Spin Collective, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Ulderico, Naples, Italy

Borbala, London, UK

Anubis, Pontevedra, Spain

Thomas Bo, Copenhagen, Denmark

Giusy, Caserta, Italy

Shira, Berlin, Germany

Emily, Mexico City

Gerardo, Naples, Italy

Jana, Bremen, Germany

Irak, Estado de Mexico

Miriam, Basel, Switerzerland

Sophia, Gothenburg, Sweden

Paula and Patrick, Montreal, Canada

Oscar, Iztapalapa, Mexico

Martha, Xico, Mexico

Colonial practices implemented by the colonizers continue to happen as an everyday reality against the Indigenous communities that continue to resist.

Colonialism obstructs the possibility of a viable and ecologically sustainable future for all members of society in the Americas.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

But we continue to meet (here is our first meeting in 2009 when I began to work with the Community Museum), to discuss and to resist.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum.

Courtesy Valle de Xico Community Museum

And the Valle de Xico Community Museum continues – in exile.

Maria Thereza Alves, 2021