Modern Animal by Yevgenia Belorusets is a strange book. It’s prophetic, ironic, dreamlike and disturbing. Published in 2021, in the context of a post-Revolution of Dignity Ukraine and the low-intensity conflict in the Donbas, today it’s a read that takes on more critical overtones following Russia's large-scale invasion.

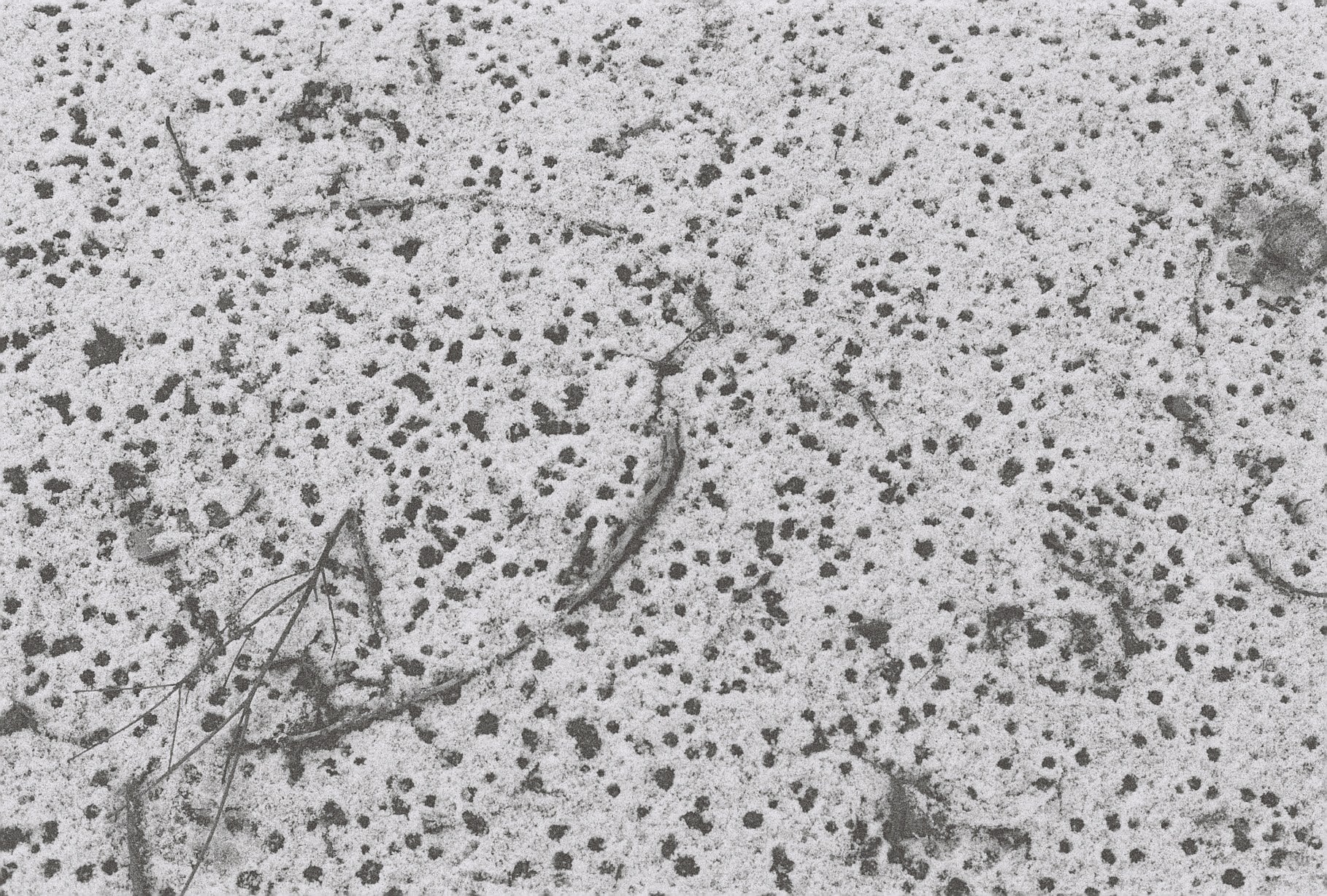

Belorusets (Kyiv, 1980) is a Ukrainian journalist, photographer, activist and writer, active between Kiev and Berlin, who assembles photographs and texts that focus on animals. These include mock lectures, fairy tales and diary pages. Sometimes human beings speak, sometimes it’s the animals themselves. The pages are interspersed with mysterious, raw, black and white images: they represent domestic or wild environments and animals that have left a trace behind them. After spending the first days of the Russian invasion in Kyiv, recounting those moments in a diary that has circulated around the world (the diary was also published in Artforum and presented at the Venice Biennale), today Belorusets is in Berlin, grappling with her life that has been disrupted by the shocking situation in her country. We reached her via Zoom.

Luca Fiore: From what core needs was Modern Animal born?

Yevgenia Belorusets: The idea for this book emerged in 2017-2018. And of course, from today’s perspective – that of the war that is being fought – the whole concept looks different than it was at that time. Actually, as a writer and photographer, I have always been interested in human rights and I have always seen animal rights as the deepest representation and understanding of human rights in society. I had long wished to have the opportunity to study this aspect of life within my Ukrainian society. In 2014, the Revolution of Dignity brought many changes to the country, in particular a new vision of human rights in civil society. And one of the aspects of this new era of awareness involved animal rights. Some small groups have begun to engage in this field, pushing to change Ukrainian laws. When I was working on the book, many things were changing. Until then, our country had Soviet laws that allowed the use of animals in circuses. Or it was possible to use wild animals to train hunting dogs, which was very common in Russia. But, thanks to the struggle of these activist groups, the laws have been changed, providing more and more protection for animals and also more awareness in society about what an animal is. Working on this book meant, on the one hand, fixing these ongoing changes, and on the other hand, studying how Ukrainian society, in its different contexts, imagines the human-animal boundary.

L.F.: It is a book that alternates between writing and photography. How are these two mediums related?

Y.B.: When it comes to photography, I have always been fascinated by its ability to objectify the object of its interest. I was working on several series of photographs, collecting interviews and writing short texts on this subject. But beyond what one may think about photography, I realised that it cannot objectify an animal, because the animal cannot give its assent to be portrayed. The animal cannot sign any document to testify that it really wants to do so. And beyond that, photography is sometimes even unable to capture the subject it desires. So, I was working on the idea of the failure of photography, the impossibility of a human being to understand an animal, to create a space where an animal can be clearly understood so that we can comprehend what we can do with it. But also the impossibility of capturing it and seeing it in all its details. I was interested in the opposite of animal photography, committed to showing as much as possible, which creates the illusion that we can see much more with photography than we can with our eyes. My strategy was actually to work against it, to show that even if we want to, we are unable to see most of what we have imagined. We can see only a part of it. And it’s unclear if what we are seeing is true. It is hard to understand what we are actually looking at. It is difficult to distinguish what we’re seeing from what we’re really looking at. My main idea was to work with the imagination in order to understand what the animal in front of our camera is, and what our capabilities in catching it through photography are. Pictures, if you think about it, are a kind of cage for animals. In the book, text and images work in parallel. The photographs are not illustrative of the story, but arise from the same kind of interrogation.

L.F.: Why did you decide to use different forms of writing, such as lectures or journal entries?

Y.B.: I use various stylistic forms, including that of the Soviet era. At that time, it was taught that the human being was the pinnacle of creation and animals were just tools. New Animals was already completed by the time the large-scale Russian invasion began, but there are already sections that refer to the lack of care and crimes against animals in war zones. On 24 February, I was in Kyiv where I started a war diary and I was in contact with the keepers of the Kharkiv Zoo and with the animal protection groups in Kyiv Oblast. Several people put their lives at risk, exposing themselves to Russian shelling, to take care of the animals. Or there were people who went to feed abandoned livestock. There were also those who decided not to flee occupied areas because they had to look after the animals. Now I think I might add some new texts and publish a new expanded version of this book, because what happened illustrates the cultural change that took place during the Maidan Revolution.

L.F.: What have you learnt from writing this book? In your opinion, what still needs to change in people’s attitudes toward animals?

Y.B.: Mine is an anthropological research. I try to describe, in words and pictures, what the situation I see around me is and how mindsets are changing. I don’t have my own view on what a human being is and what an animal is, and what the difference between the two is. And my work is at the level of the imagination: how people imagine their being human and how they understand themselves as different from animals, or how they describe another living being. It’s kind of like going to see what’s behind the curtain of a theatre. I’m interested in understanding what the different configurations of these imaginations are.

L.F.: You could have written a thematic essay, but instead you used literature. How come?

Y.B.: I think that actually we cannot create a logical and clear image of something that we imagine as an animal: something different, something we can’t really understand, that is not us or something different to us. For me these interruptions in reasoning are logical, they are ways of thinking that are always interesting. And I think I discovered them specifically by studying this topic. So I was getting deeper into dreams or fragmented thinking. There is actually some structure in the book that I believe is connected to how we write music. Because the raw elements of the writing methods that repeat themselves throughout the book have connections with manners of speaking and writing. I’ve always been interested in showing different voices and making sure that when you read you hear different voices, not just the one voice you can really get into, but also the voice of what you are trying to observe.

L.F.: Some might say that in the tragic context of Ukraine today, the issue of animals and their rights is very marginal.

Y.B. : If you read my book, you will see that I’m not writing about animals at all, but rather, about people. Animals are just a “big other”; the animal is a big other “something”. It is the idea of something that is in some way close to the human being, but also very different. By studying it, you can understand what it means to be different and how this in fact differentiates reality. This gap between the human and another creation is at work in society. And that is very relevant in today’s Ukraine, as well as in other countries.

Interview by Luca Fiore, septembre 2022

At the invitation of Federica Chiocchetti / Photocaptionist