Hollywood is currently going through a triple crisis, which has made it a recurring subject in films, in which the beginnings of silent cinema are being re-examined (Babylon, Damien Chazelle); paths between personal vocations and the collective future of its productions are being mapped out (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino); and what remains of its hold on creative cinema is being explored with varying degrees of nostalgia (The Fabelmans, Steven Spielberg). Firstly, there is an economic crisis, which has undeniably had an aesthetic effect, a sort of “Marvel-isation of Hollywood”, as Martin Scorsese diagnosed with chagrin in an article published in the New York Times in autumn 2019. For the director of Taxi Driver and Casino, the development of superheroes in the studios has brought about a transformation in production modes in the United States.

This transformation was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which prevented hundreds of thousands of spectators from going to cinemas, forcing them to watch films on their computer screens through Netflix subscriptions or by activating the VOD services of television channels. This was the second major crisis to hit Hollywood: a crisis in the system with massive financial consequences that have inevitably altered the magic of the movie theatre.

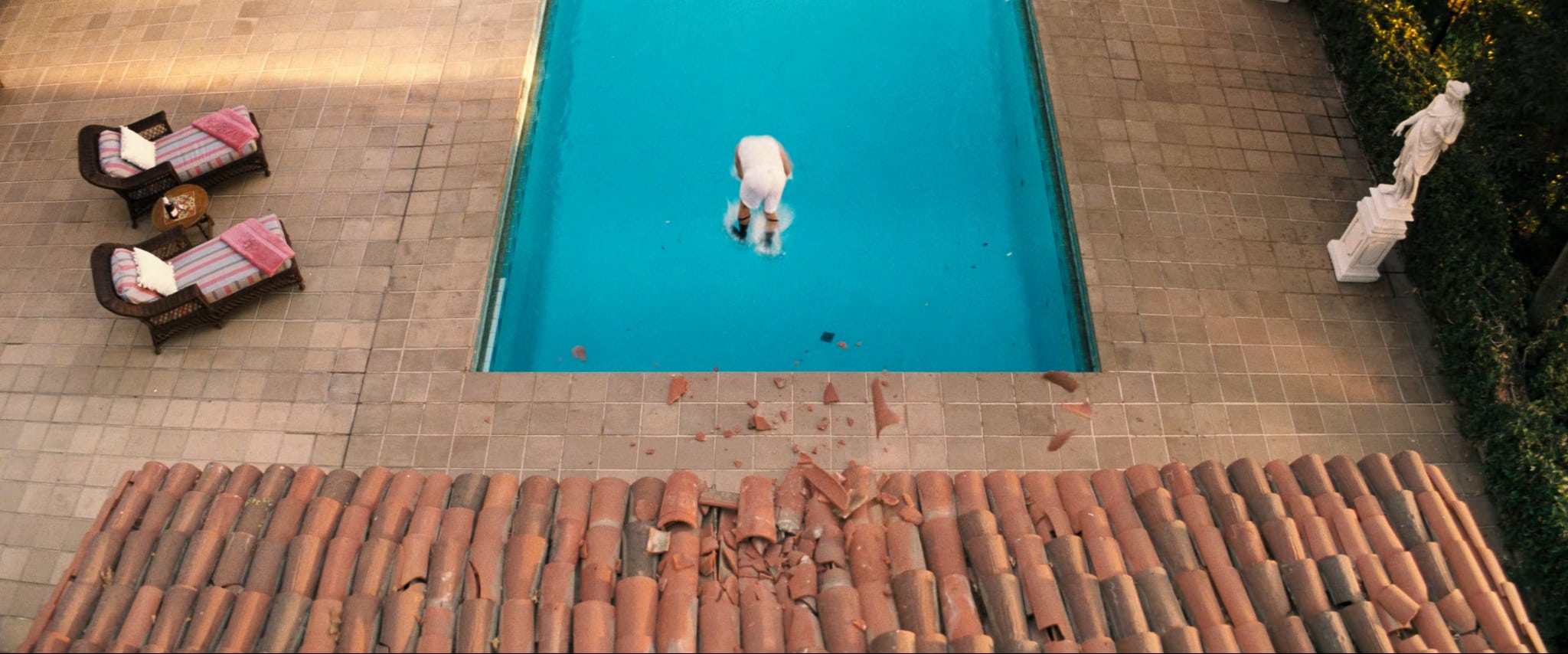

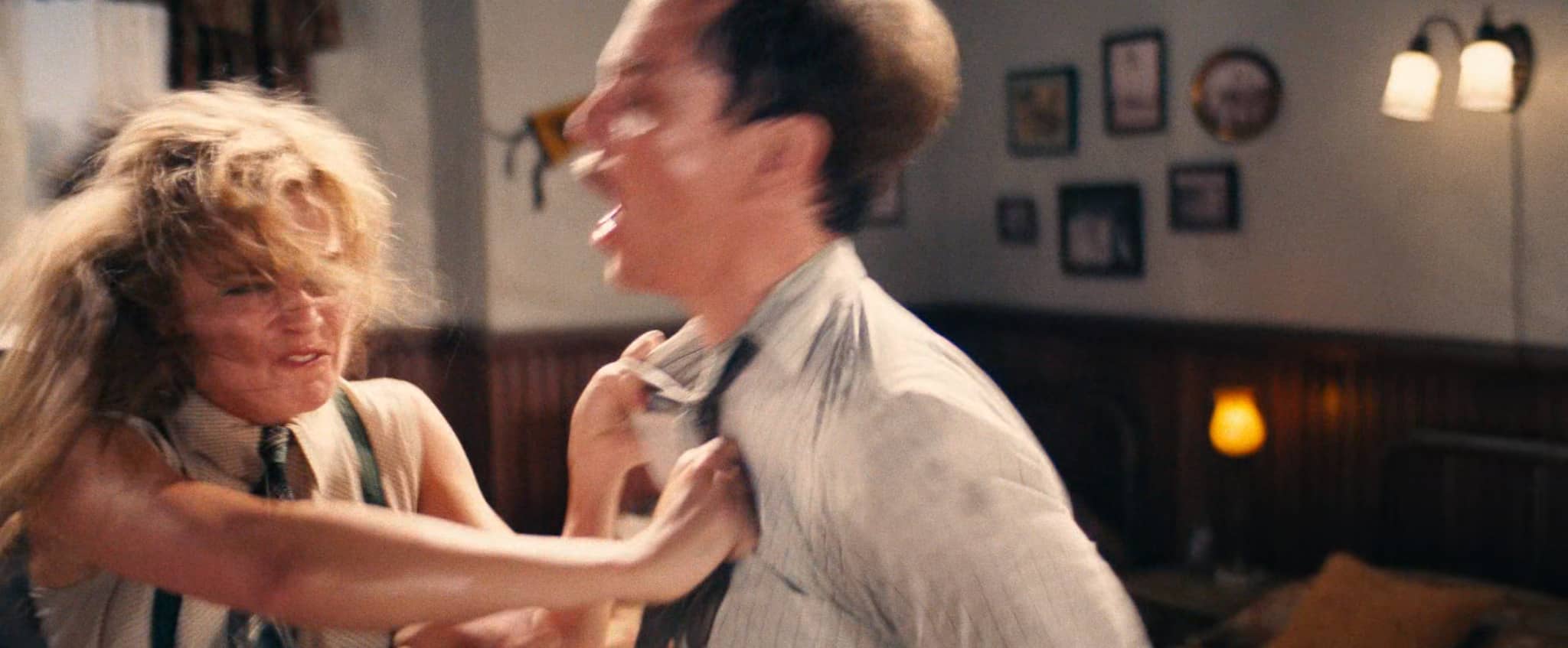

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

Finally, there has been a third crisis, one less talked about but no less decisive for all that, a political crisis from which Hollywood has yet to recover. The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States in 2016 terrified the leading protagonists of the Hollywood industry. What happened? The critic Jim Hoberman offered a simple summary of the situation: with Trump a “happy ending” was no longer possible, because the very foundations of Hollywood’s cultural hegemony had been affected, namely the fact that the president is the “leader of the free world”, the defender of universal liberty. But he has to care about this, or at least create the impression that he cares about it. Which was hardly the case with Trump. The 45th president of the United States unintentionally broke this pact, which has caused lasting damage to Hollywood’s imperialist strategy.

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

Trump’s presidency seemed to create a split in Hollywood between the film-makers who were seeking to restore its lost aura and those who were happy to reveal its dark side, the face of death. It was as if the darkness of the Trump presidency had led some to reveal the harsh underbelly of a society of spectacle whose hegemony was precarious. Chazelle belonged to this latter group. His film Babylon was one of a series of works – ranging from Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder) to Mulholland Drive (David Lynch) and The Legend of Lylah Clare (Robert Aldrich) – that questioned Hollywood both as a vehicle for dominating collective imaginations and as a generator of unequal practices within this dream factory.

Chazelle nevertheless chose a different path from that followed by his illustrious predecessors and his contemporary colleagues. Indeed, Babylon’s uniqueness lies in the way the film questions our relationship to the spectacular today, to the future of what Jacques Rancière called ‘the democracy of entertainments’ and to the role assigned to the public when it is invited to celebrate the ‘cult of the art’ of film-making.1 Even though Chazelle’s subject is the gradual transition from silent movies to talkies in the late 1920s, his film is not a simple historical reconstruction of the end of a certain golden age of film-making. Beneath the surface, it also explores this period of upheaval in Hollywood’s history in the light of the turbulence it is currently experiencing, at a time when cinema as an art form is now just a pleasure aimed at a handful of film-loving aesthetes, and when it appears doomed to disappear in a wide-reaching entertainment enterprise that is developing online.

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

Babylon as temporal object thus offers a diagnosis of the state of Hollywood, in a constant interlinking of the on-screen reconstruction of the past and the present with its numerous crises. And this reconstruction avoids the retro tendency represented by, for example, The Fabelmans, with its smug, fetishising museumification of film. The artifice of the technical apparatus of film-making presented by Chazelle – lighting, costume, makeup, sets, etc. – is seemingly highlighted, but this visually striking exaggeration tends above all to reveal the material processes of the recreation of reality during the silent era. Hence the very concrete use value acquired by objects in Chazelle’s film, something that is conspicuously missing from Spielberg’s, which is frozen in a past time that struggles to solicit perception of this past from the tribulations of our present.

Babylon is also contemporary because its structure mimics the ways in which we circulate today between ever more heterogeneous visual and aural material. Images – amateur, artistic, media, institutional, etc. – continually collide with each other in the different spheres of our lives; we sometimes become stupefied spectators enveloped in a morass of signs marked by the risk of a lack of distinctiveness. It was Chazelle’s formal choice both to abandon himself to this lack of distinctiveness and to favour a process of differentiation among the film quotations that occur throughout Babylon. These are taken from every genre, and Chazelle does not have the vanity of the know-it-all who, like Tarantino, overplays the satisfaction he gets from juggling the avatars of a so-called popular culture with the accomplishments of an art presumed to be noble.

The liquid element visible throughout Babylon is a recurring motif that makes it possible to grasp the permanent moves from one genre to the next, and even the shifting coexistence between these composite references. Urine, vomit, faecal matter, saliva, sweat and even tears are all fluids that are projected onto the surfaces of bodies, sometimes bringing them into contact with each other, and which have a threefold vocation. On the one hand, they convey the underside of the success stories of Hollywood in the 1920s and 1930s. What do we see if we peek behind the curtain of the already well-established star system? Shit, quite literally, including an excretion from an animal which is shown right at the beginning of the film. This is not a metaphor, it was the reality of the industry.

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

Secondly, in the short circuit described above between Hollywood’s crises and the political breaches in Washington this literalism refers to several episodes in Trump’s misadventures at the boundary between the private and the public. The American electorate turned away from them in disgust or disbelief: the practice of the golden shower (a sexual ritual in which someone urinates on their partner) that the former president is said to have organised during a trip to Russia before his election and which Chazelle no doubt had in mind during the orgy scene at the beginning of Babylon; the sperm and cash flowing from his extramarital relationship with the former porn star Stormy Daniels (who was paid $130,000 hush money in order to conceal their relationship); and the famous streams of fast food (hamburgers, nuggets, milkshakes, etc.) that pass through the former president’s digestive tract. This is not a theme explicitly taken up by Chazelle, but Trump’s erotic practices and diet resonate with his film’s scatological scenes, as if the cruel underside of Hollywood were linked by a dotted line to a disarming way of governing that was almost fatal for American democracy.

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

Finally, all of these fluids streaking across the surface of the screen obey an editing principle. As we have pointed out, although Chazelle’s film-making methods can be seen as a way of documenting our circulation between images today, they also highlight in parallel the possibilities offered by this same fluidity when it comes to the traversing of cinema. Thus Babylon revisits the orgiastic sequences in the chilling mansion in Eyes Wide Shut, borrowing from Kubrick the automatism of the postures in the lovemaking, while adopting a supercharged tempo that refers to the real decadence of Hollywood parties in the 1920s. One thinks again of the deliberate vomiting of the character of Nellie LaRoy (played by Margot Robbie) in Los Angeles high society: it is as if we are witnessing the irruption of the Farrelly brothers’ comedy in the flamboyant style of Visconti’s Leopard.2

Damien Chazelle, Babylon, 2022

If Babylon has a critical dimension, it lies in the subtle passage from the vulgarity of a lost Hollywoodian world to the vulgarity of a contemporary art of cinema that returns it to its own territory, while questioning our convulsive relationship with images today. Reconstructing Hollywood comes at this cost: showing its ugliness, giving yourself up to it, in order, in the end, to experience the strange pleasure that consists in no longer burying your head in the sand.

Dork Zabunyan

Translated by Bernard Wooding