The story told by Gilles Gerbaud, Laurence Vidil and Raphaël Chipault is a story of objects; or rather, a story of objects that are more than objects, as they beckon and create ties amongst different people and countries, recalling the past and looking to the future.

It all began with a stool, Gilles recounts. An abandoned stool he found in a chicken coop in the Drôme department of France. Since his student days, Gilles had never wanted to produce new objects in a world already overflowing with them, exploring photographic drawings for this reason. For him, the stool represented the idea of a true encounter: an encounter with an object made, cobbled together, from other objects; an encounter with a social world where individuals base their uses on forms of self-production; an encounter with Raphaël, a photographer focusing on museums and more. Gilles predicted that Raphaël would be able to ‘create a photographic existence’ for this stool and shed light on the ways it is, so to speak, transitional. This is how their collaboration began.

I’m not quite sure what we’re talking about, until Gilles shows me the photo of the famous stool treated in the style of a museum work. It wasn’t what I was anticipating and surprises me. We look at it together, Gilles, Laurence, Raphaël and I, commenting in turn. We bear in mind the key terms of the Palm commission: restitution, reproduction, resumption – the three Rs. And we remark that this photograph embodies them perfectly. Reader, perhaps you’re also looking at it now, and we can carry on the conversation with you.

“La piel de la banqueta” © Le Tiers Visible (Laurence Vidil - Gilles Gerbaud - Raphaël Chipault)

Courtesy Galerie Françoise Paviot, Paris

My first impression is the object’s realness, its presence. Whatever interpretation may be formulated, something asserts itself. Yesterday in passing, I looked at beautiful photos of African sculptures set on the gates of the Gare de l’Est in Paris and felt something similar, elicited by a photograph with the qualities of an analytical drawing. Knowing, for example, that to guard against the risk of picking a poisonous mushroom and properly identify the specimen, it is better to refer to a botanical illustration than a photograph indifferent to decisive details. The idea of ‘reproduction’ entails more than a snapshot. In an object’s transfer from one ontological status to another, there is either loss – the object cut off from its own possibilities – or enrichment. At first glance, nothing about the chicken coop stool catches the eye. Wagering that it can travel and become the object of a shared experience imbues it with existential depth. It is a way of calling into question our habit of reducing photos to ‘images’ and thinking that a photograph is the sign of the object’s loss, disappearance or even death, for the most mystical among us.

Raphaël defines his photographic intention as follows: ‘the idea in making this photograph was for the object to blur into the grey background, trying to turn it into a sort of monochrome, standing out in itself through its material presence and human element, without the accentuation of lighting. I wanted to question the ambiguity of the 2D depiction of a 3D object in a way removed from my photographic practice of museum objects, wholly striving to highlight them.’

The stool’s properties are heightened via various photographic processes, including a luminosity revealing the relief of each piece of wood, the elements of its assembly, nails, screws, boards, the smallest details. What it is, how it was made and the purpose it serves are clearly visible. As in reading a well-made guide, it beckons you into its production process. But there is no aestheticization at work. Certainly, the photo highlights the stool’s aesthetic qualities – through, for example, its slightly low angle, the precise proportions, harmonious materials, efficacy of form, etc. – but it is devoid of any romantic halo. Once again, what is appreciated is what is there. There is nothing evoking an operation of essentialization, symbolization or sacralization.

And yet, the stool is removed from any concrete situation. Its dimensions are guessed but not known with exactitude. It is willingly associated with a rustic, rural environment, but without certainty. All of this is discussed, and it is agreed that its decontextualization does not entail its displacement. It doesn’t appear detached from the world, like an atemporal symbol, but very much part of the world. The photographic gesture giving rise to this is objectification, but without any reduction to mere observation: what is objectified are the uses, i.e., the possible ways in which this small item of furniture can become the partner of interactions that are very much alive. The form is efficient, the materials are solid, the potential uses are varied. The object has been sculpted by the passage of time, wear due to its use, the skill of its maker, as well as the gaze of photographers and their audience.

In observing the photo of the stool, which sparked the collaboration between Gilles, Laurence and Raphaël, I told myself that we could stop there, that further discussion wouldn’t add anything more, just confirm Gilles’s initial theory and my own impressions. Which is what happened, except that many other things were added along the way (too many for everything to be shared here).

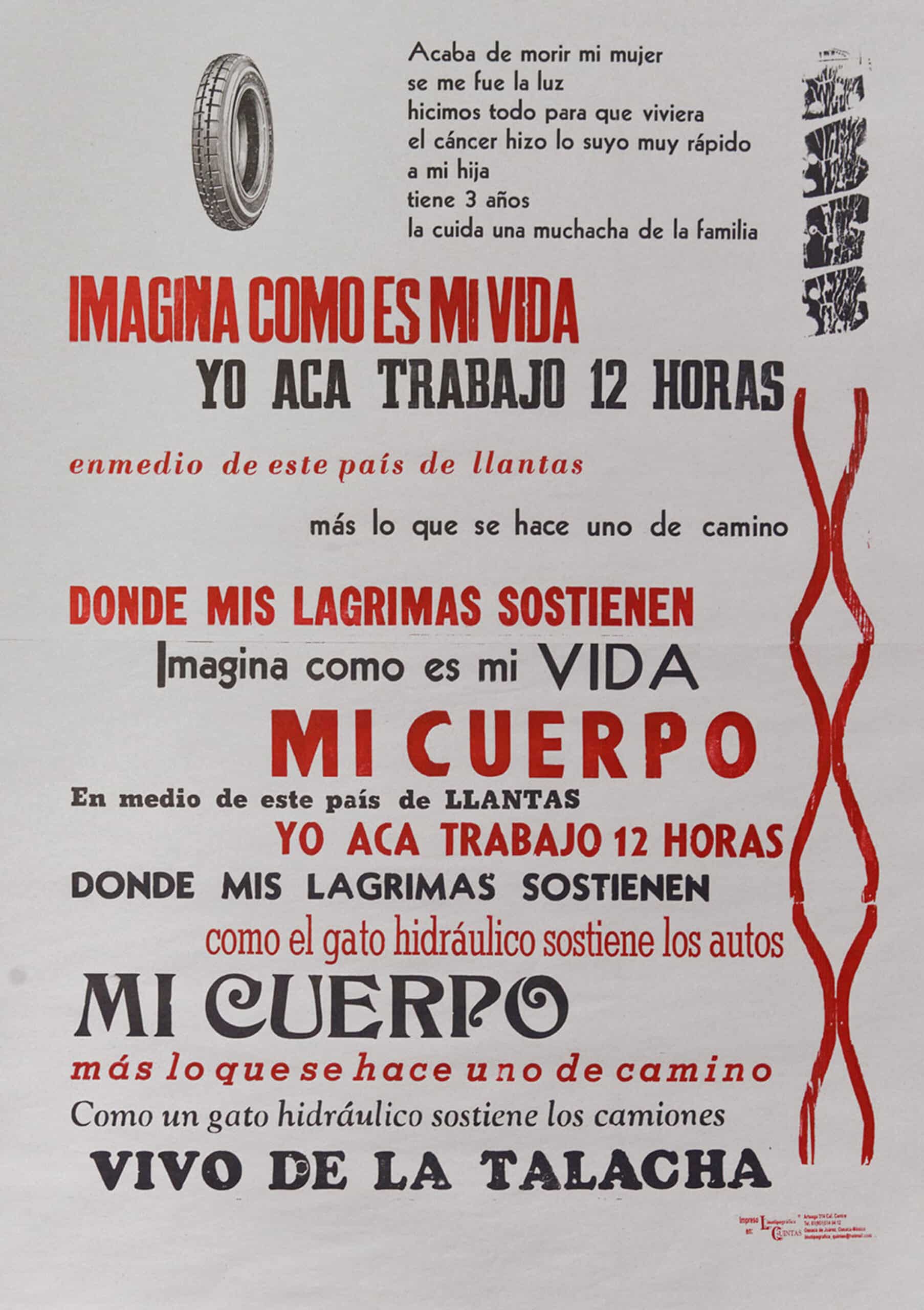

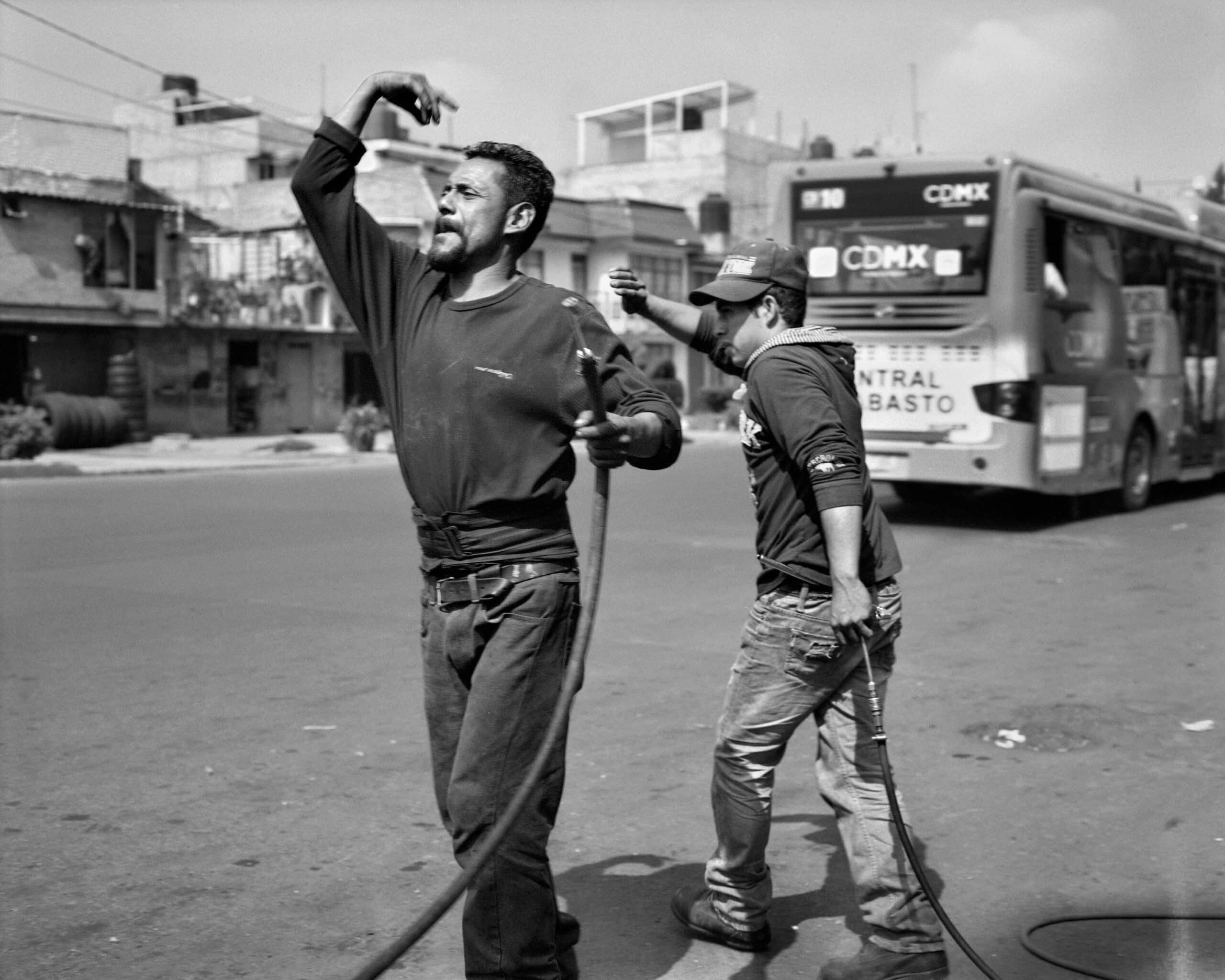

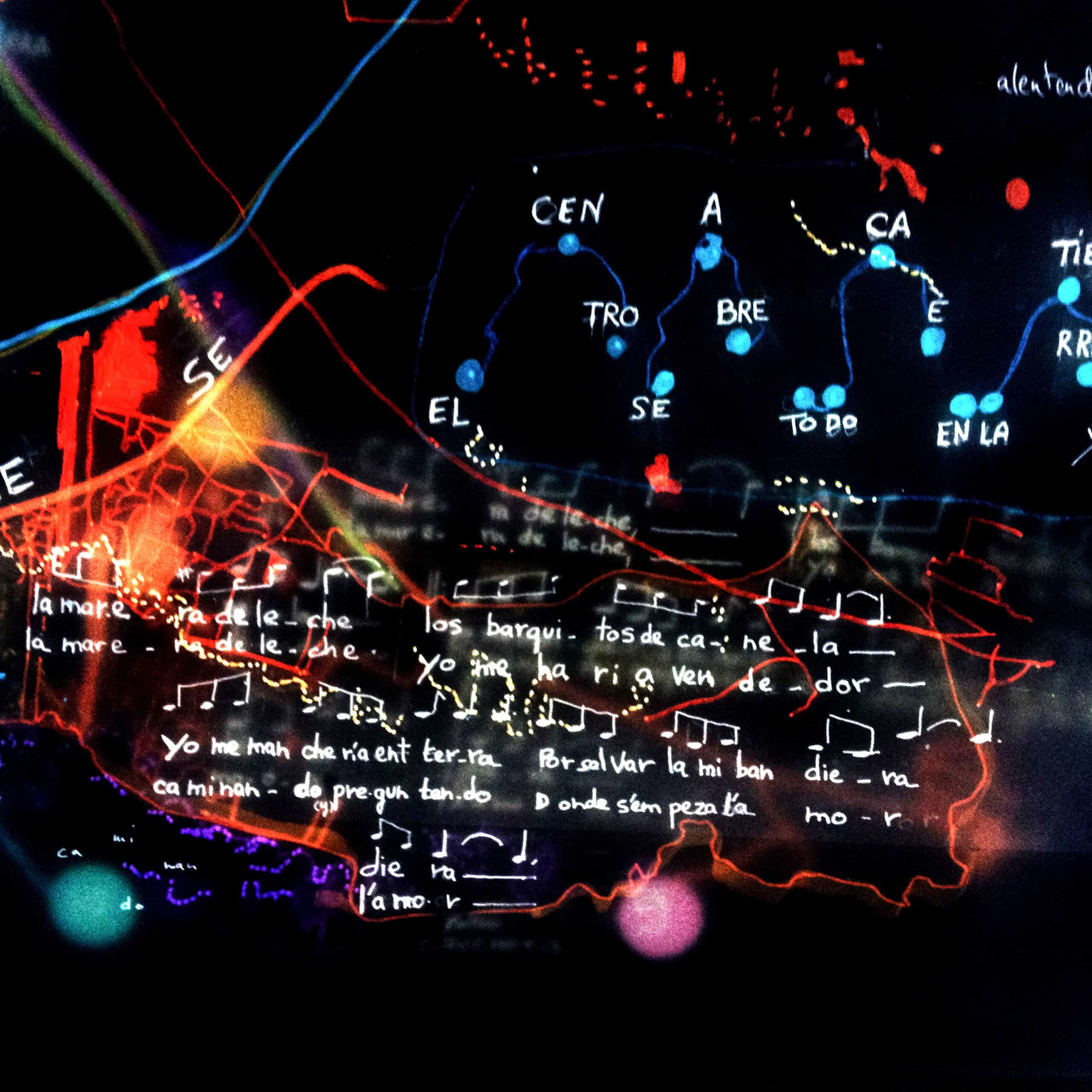

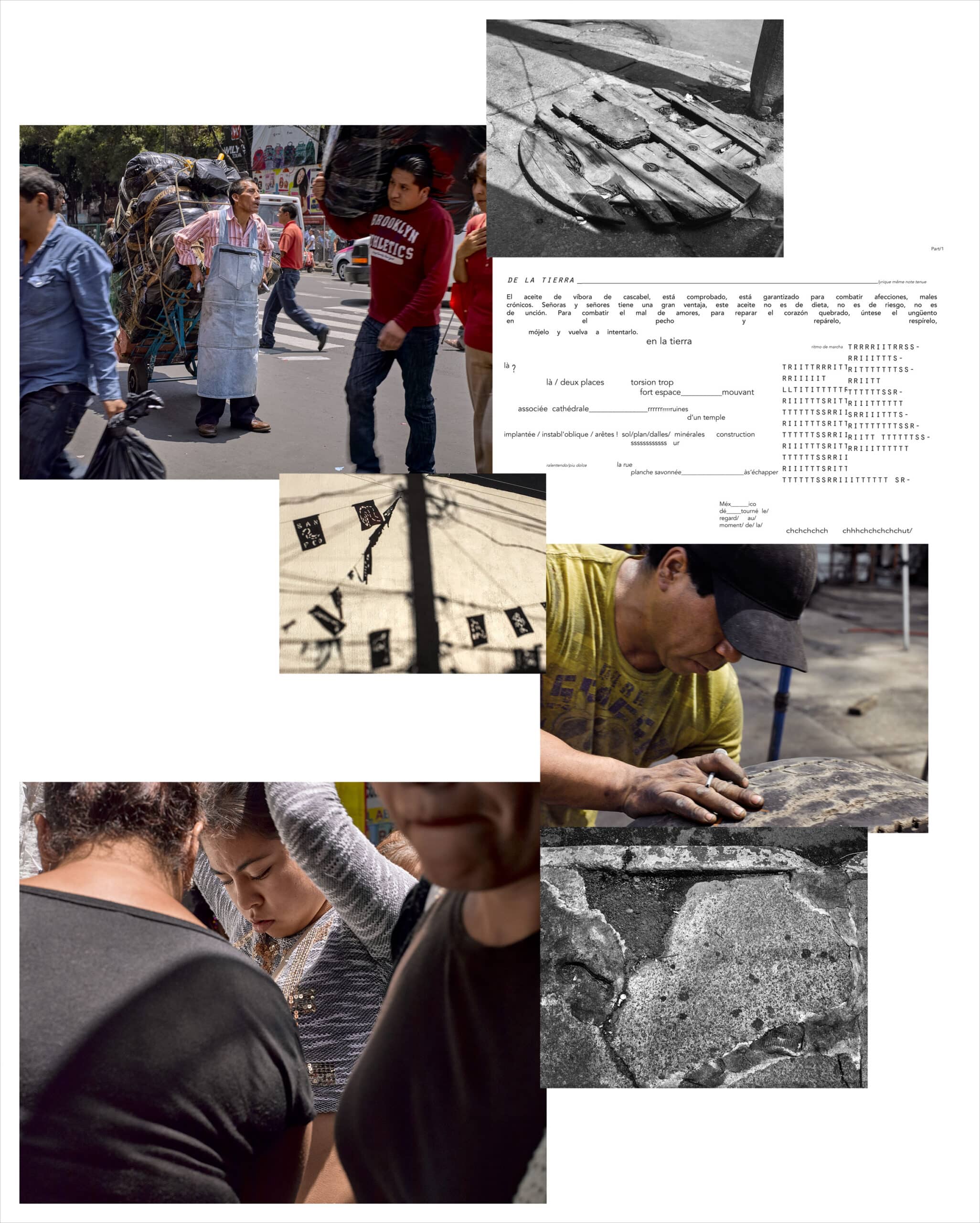

The collaboration between Gilles, Laurence and Raphaël developed on different sites, including Mexico City, which we discuss at length. It is characterized by a consistent photographic logic, meticulous efforts to collect and take samplings – of sounds, words and languages, assembled by Laurence, who turns them into the elements of an unfinishable score, shown in stages at each performance: a close-up view of cobbled-together daily objects like trestles of different sizes (known as burros in Spanish) that people make to use for stands, eating and more; sidewalk hazards caused by wear, ground collapse and surfacing roots (Mexico City, my conversation partners tell me, is a giant city built atop a dry basin, with unstable ground.) Beyond the photographic work, the three-plus-person collaboration involves toying with transposition in various ways – for example, rubbings of tires repaired by vulcanizadores (vulcanizers) on a piece of large black textile, traces of that world echoing the photographic or sound imprint of the city; typographic prints of poems featuring work expressions and terms used by vulcanizadores on posters intended to be pasted to neighbourhood walls; highlighting of the ground surface, the ‘visible portion of the recording of what lies underground’. All of this is rendered in the form of ‘palimpsest walls’ and large sheets to turn like the pages of a book more than two metres long spread over a table-high surface.

Courtesy Galerie Françoise Paviot, Paris

In speaking of Mexico City, we broach the subject of another R: repatriation. I know this term well through my anthropological readings. In response to the questions ‘Why ethnology? – i.e., scientific knowledge of a foreign culture until recently considered ‘primitive’ – and ‘What to make of ethnographic knowledge patiently drawn up by ethnologists?’, we reply that a certain image of humanity shared by all is derived from this. It is the image of a pluralist humanity – astonishingly varied, impossible to hierarchize, imbued with dignity and equality regardless of the forms it takes, so long as they are forms of life (rather than forms of death). Another response it that the repatriation of knowledge of distant cultures to the bosom of the researcher’s culture sparks greater modesty and tolerance in them and in their fellow citizens. The diversity of customs is a vantage point for observing one’s own culture, relativizing and contextualizing one’s beliefs, potentially in an unfavourable comparison, undertaking their criticism. It is also explained, in the framework of the major cultural destruction of which many peoples have been victim, that the recorded and collected cultural elements might help indigenous populations themselves to draw up cultural charters, assert rights in terms of heritage and territory, re-establish certain traditions, rediscover a language that had been lost.

In the case of Mexico City concerning us here, repatriation encompasses photographs, sounds and words providing an account of ‘the living part of the city’, imbued with sociability and highly free ways of being together – which are in contrast sorely lacking in Paris and in most of our cities. The intermediate space between home and street that is the sidewalk is a place where street vendors, tire repairers, craftspeople, coffee carts and more cross paths. This, as Raphaël says, is where the experience of the vacant lot or street known as a child can be found, in all its freedom. And for Gilles, Mexico City allowed him to connect with pre-Hausmann Paris and understand ‘that the aspect of the cobbled-together, fabricated, actual object has been lost – objects that haven’t been bought or industrially produced’. Throughout urban space, personal gestures are expressed. The type of homogenous approach that our urban habits impose upon us is not found, but rather, an incitement towards individual intervention. The street is a space of active participation – extremely clean and respected, swept and covered with plants by inhabitants. This conception has been gradually disappearing over the past century, which we lament alongside Patrick Geddes, Walter Benjamin, Lewis Mumford, Henri Lefebvre, Lucien Kroll and others.

Lastly, repatriation encompasses the impressions resulting from the experience of having adopted the country and of having been adopted, welcomed. Laurence says that she feels attachment to a country that has welcomed her subjectivity. But welcome implies difference: welcoming someone means taking them as they are and granting them a place without expecting them to abandon their culture and assimilate. Unlike gestures of sacralization or, conversely, instrumentalization, repatriation implies the virtue of properly welcoming an encounter between foreign beings who discover what they have in common over the course of their time spent together.

Joëlle Zask

Translated from French by Sara Heft