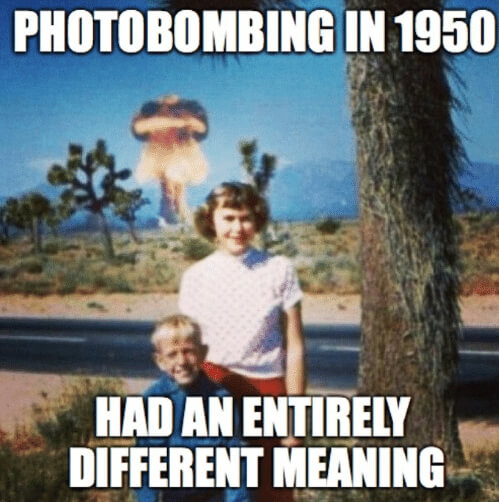

Back in 2016, when I was compiling an irreverent “Anti-Glossary of Photography and Visual Culture” for the catalogue edited by Lars Willumeit for Krakow Photomonth, I couldn’t believe my eyes upon seeing the results to my search for the word “photobook” in the Oxford English Dictionary. Not only did the word “photobook” not exist for the OED, despite the object photobook having been around since the 1840s, but a bizarre, bellicose-sounding term was showing in the results instead, as an accepted word in our current vocabulary that first appeared in 2008 in a now-defunct blog: “photobomb”. My immediate reaction was, quite frankly, “What the hell is that?!”. Little did I know that a whole hilarious Pandora’s box would open up, taking me here today to propose a sort of phenomenology of this curious photographic trope.

So then, let’s start at the beginning, with its definition: photobombing means “to spoil a photograph by appearing unexpectedly in the camera’s field of view as the picture is taken, typically as a prank or practical joke” (OED). Both a verb and a noun, the term “photobomb” has its own dedicated Wikipedia page, is a tag within such major suppliers of stock images as Getty Images, and was even judged “Word of the Year” by the Collins English Dictionary in 2014.

Ontologically speaking, it is a hybrid object that lies approximately between two genres compellingly explored by Clément Cheroux: a “fautographie”, since the aim of the person disrupting the picture is precisely to ruin it and turn it into a photographic error; and a “récréation photographique”, given its playful nature. And Cheroux’s choice to illustrate the introduction of his book Fautographie with Francky Stadelmann’s “Group Portrait with Self-Timer”, from the 1991 eponymous French game contest in which amateur photographers were invited to send in their mistaken pictures, prompted me to speculate on a possible list of photobomb characteristics. For example, is the intentionality of the photobomber a key component of any photobomb? Stadelmann’s picture could be described as an accidental photobomb, since the person intruding on the image with his chest, arm and mountain stick, which funnily enough appears at the very center of the image, could presumably also be the photographer, who may have miscalculated the delay between pressing the shutter release and the shutter’s firing.

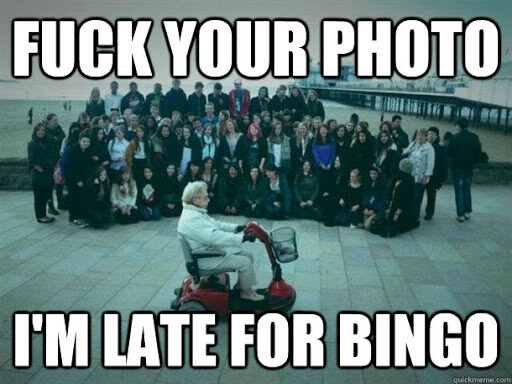

Thanks to memes, those viral internet-based photo-texts, I also learned that sometimes, photobombers have no choice: their priorities are so urgent that they are forced to ruin a photo, like the little old lady running late for bingo—ubi maior minor cessat, as they say. Needless to say, it is difficult to talk about intentionality when the photobomber is an animal. And you would be surprised by the number of pictures floating around the internet with all sorts of real or fake animals spoiling tourist views or wedding photographs.

Another characteristic of the photobomb is that, as an act of trespassing and posing distraction in the foreground or background of a picture during a photo shoot, it is typically unbeknownst to the photographer. This could imply that the photobomber is a sort of animated “optical unconscious”. However, the photographer often, though not always, becomes aware of it in the manner of an omniscient narrator, as they are distracted by the intruding photobomber – at times interrupting the shooting to “save” the picture. But it does not go without saying that the subjects being photobombed realize it in the very moment it is happening, especially if it is occurring in the background. It also depends on the degree of the “aggression” orchestrated by the photobomber. For instance, tourists around the Leaning Tower of Pisa, in pretending to hold it up for the clichéd souvenir picture – as in Martin Parr’s famous 1990 photo – practically hand the photobomber the temptation on a plate. It is inevitable that the subjects realize they are being photobombed, if, for example, the intruder high-fives them.

Intriguingly, aggressiveness within photography has usually been associated with the picture taker if we think about the verb “to shoot”, certain iconic scenes from Antonioni’s Blow Up, or the annoying paparazzi. With the photobomb we could say that there is an inversion of roles, as the aggressor becomes the unwanted intruder who “bombards” the picture with their unsolicited presence.

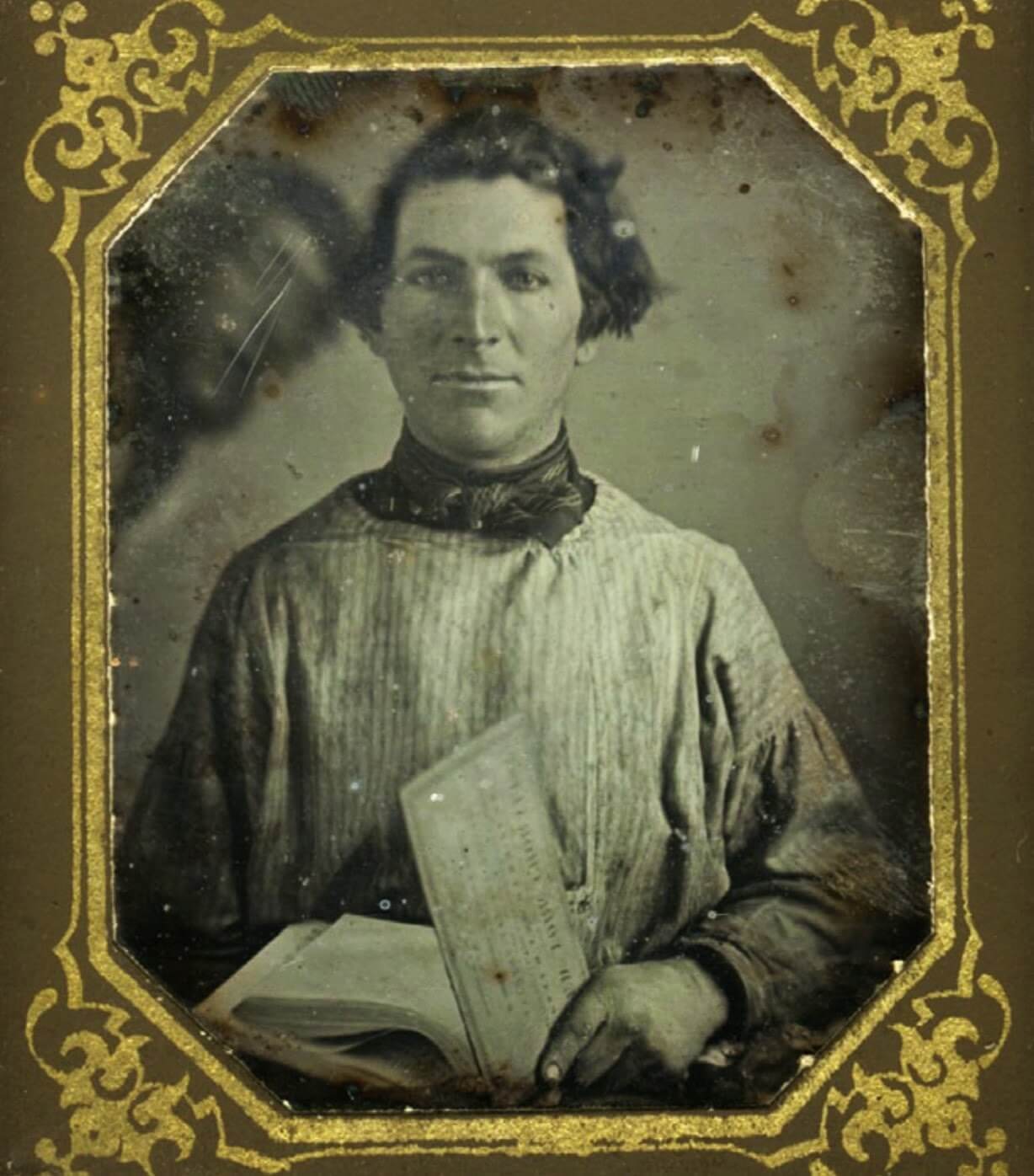

In my effort to retrace a very short history of this eccentric photographic phenomenon, I was quite pleased to read that the presumed first photograph to be photobombed was made by a woman in 1853: the Welsh photographer Mary Dillwyn (1816–1906), who apparently used a smaller camera with a fairly short shutter speed. Indeed, the long exposure time of early photographic processes could have been an obstacle for the success of photobombing, as the opposite phenomenon—namely, the risk of not properly impressing the negative even if the subject passed in front of the camera—was more likely. Dillwyn’s salt print comes with a handwritten caption, which is not easy to decipher, but I managed to read the last word: “peeping”, which likely refers to the figure in the background, confirming the author’s prescient awareness of the photobomber avant la lettre. The internet is as rich as it is unreliable, and in fact, minutes after my happy discovery of Dillwyn’s image, I found a daguerreotype portrait of unknown author and provenance, dated ca. 1840s, of an unidentified man with a book in his hands, and another man popping up into the frame behind him, which confused me even further as to the exposure time.

Mary Dillwyn (1816-1906), Sally and Mrs Reed, salt print, c.1853, The National Library of Wales

Anonymous daguerreotype portrait, c.1840s

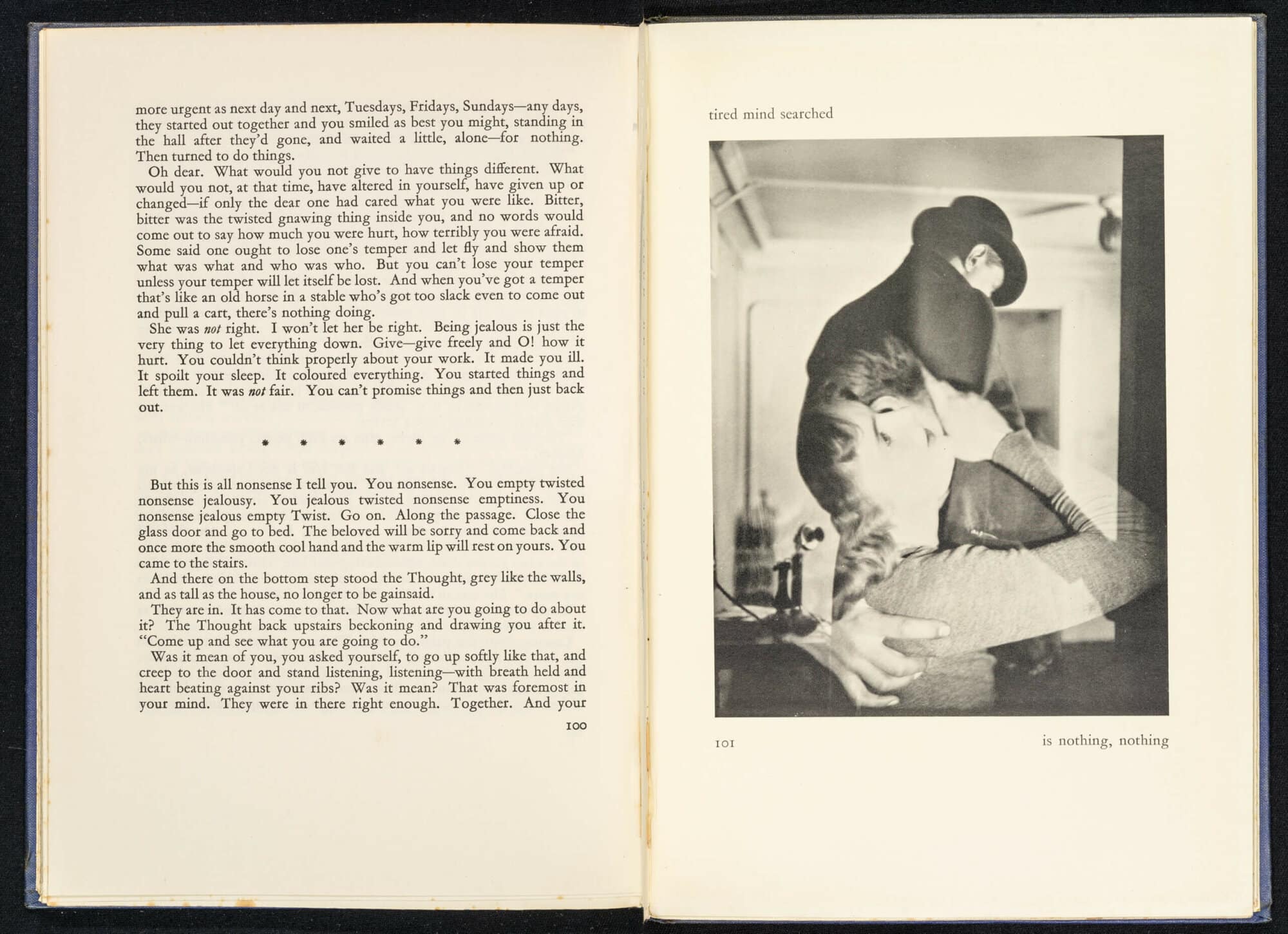

This in turn triggered the outlandish speculation that some early ghost photographs could be seen as photobombs through our 21st-century eyes. Similarly, the double exposure of Beyond This Point, illustrating the editorial, now appears to me as a “paranoid photobomb”, in which the jealous husband, obsessed with the fear that his wife is unfaithful, imagines her with her lover, while “photobombing” his paranoid vision with his own looming figure.

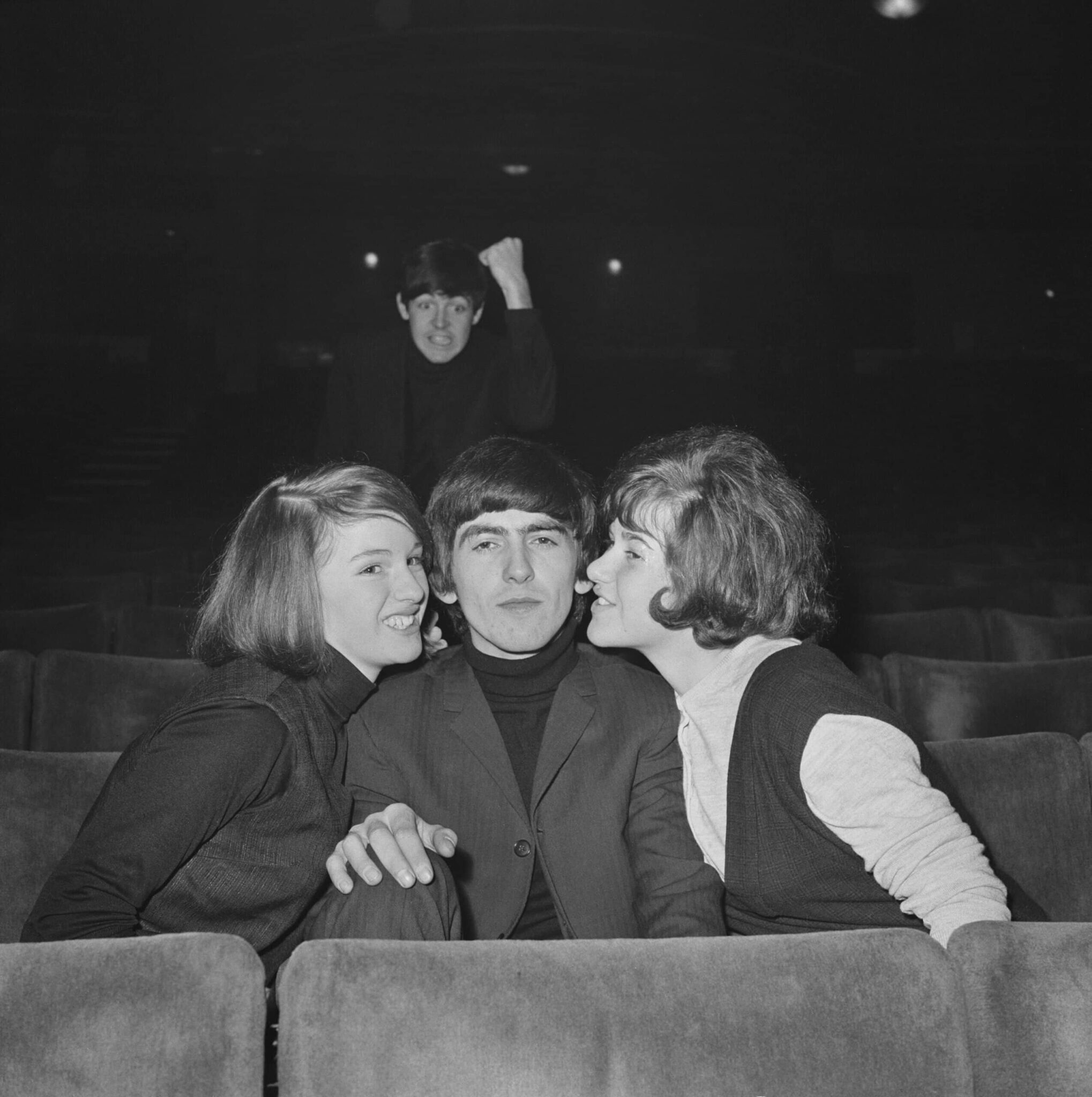

What I know for certain, as my eyes nearly bleed, bombarded with too many internet photobombs, is that those featuring red carpet celebrities are the most boring of all, with the exception of one showing Paul McCartney, who teasingly claims he invented the photobomb, intruding into bandmate George Harrison’s picture with two fans in 1964.

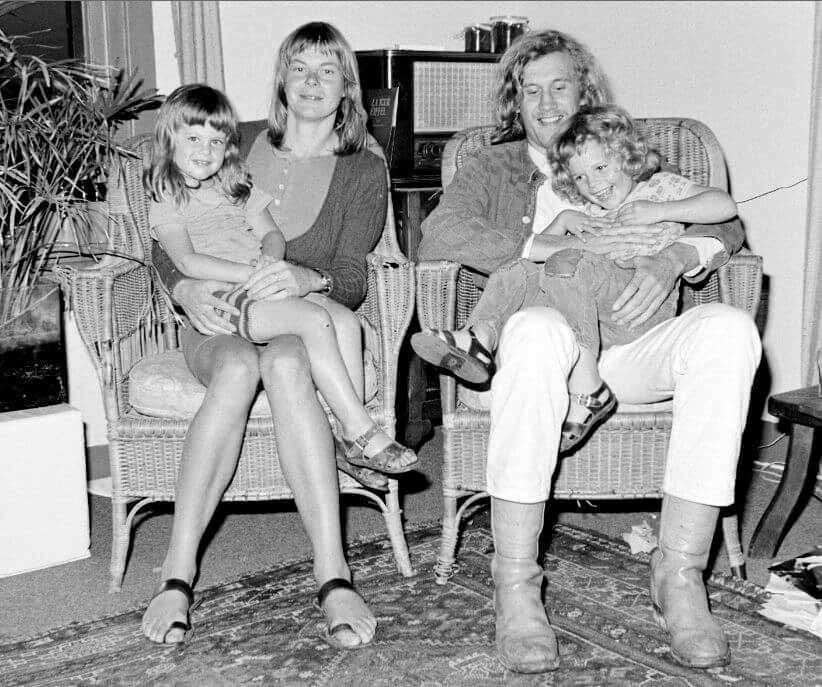

Among my favorite photobombers avant la lettre is the Dutch artist Hans Eijkelboom, who, in 1973, produced two conceptual and performative series, Met mijn gezin (With My Family) and In de krant (In the Newspaper), in which he intruded on the images with his own presence. For With My Family, he photobombed family snapshots, sitting with mothers and their two children on the sofa, performing the father figure for the camera. Despite their authentic look, when seen together, these images question the replaceability of the father figure in a family. For In the Newspaper, he remarkably managed to photobomb (in the background) pictures in his local newspaper, shot to illustrate leading news stories, for no fewer than ten consecutive days, by making sure to show up at major local events.

Photobombs can have a short life span, if we consider the infinite possibilities for the photographer to rescue the picture by erasing the intruder in both the pre- and post-Photoshop era. On certain occasions, censorship could also play the role of “rescuer”: if, for instance, the photographer who took the group photo of EU leaders in 2002—in which photobomber Silvio Berlusconi “makes horns”, as we say in Italian, behind the head of the Spanish foreign minister Josep Piqué—had decided not to circulate it. This typical gesture, which signifies a cuckold in Italy, was clearly not appreciated by the Spanish official and his wife. Thankfully, politically speaking, the picture went viral and further revealed the pathetic hubris of someone who should not have ruled (read ruined) a country for so long.

Federica Chiocchetti/Photocaptionist

Bibliography

“Awesome Guy Photobombs Tourist Pic At Leaning Tower Of Pisa”, Huffington Post, June 8, 2010

Bajac, Q. (2014). “The Age of Distraction : Photography and Film”. In Object : Photo. Modern Photographs : The Thomas Walther Collection 1909–1949 at The Museum of Modern Art. Available here

Benjamin, W. (1931). “Kleinen Geschichte der Photographie”. Literarische Welt, 18.9., 25.9. und 2.10.

Chéroux, C. (2003). Fautographie : Petite histoire de l’erreur photographique. Crisnée, Belgique : Éditions Yellow Now

Chéroux, C. (2015). Avant l’avant-garde : du jeu en photographie 1890-1940. Paris : Textuel

Chiocchetti, F. (2016). “An Anti-Glossary of Photography and Visual Culture”. In The (Un)becomings of Photography, dir. Lars Willumeit. Krakow: Foundation for Visual Arts

Edwards, P. (2015). “This 1853 image might show the first photobomb”. In Vox, September 25, 2015.

Shaffi, S. (2014). “‘Photobomb’ judged Collins’ ‘Word of the Year’”. In The Bookseller, October 23, 2014

Subramanian, C. (2012). “Top 10 Worst Silvio Berlusconi Gaffes”, Time, December 8, 2012.

Zlotnick, R. (2019). “These Are the Best Animal Photobombs of All Time”. In Distractify, June 3, 2019