Urban strolling, especially when devoid of any set goal, is inseparable from an experience of distraction, or more precisely, a series of brief moments of distraction. Not that the mind wanders at the pace of our physical roaming, or consciousness floats in accordance with the meandering of an undetermined path; in fact, the distraction that comes with walking is a back and forth between an interiority porous to what is seen and heard, and an outside world that solicits it more or less distinctly.

This request for attention – as distracted perception is indeed a form of incidental or peripheral attention – does not necessarily depend on a particular interest or specific need (to consume, eat, take transportation, etc.). It can reflect a sort of astonishment in the face of small street scenes, and the health of any big city is no doubt inextricably linked to the myriad of minute events it holds it store and that can occur at any moment. Walter Benjamin said just this in his book on the Arcades: Paris is “the capital of the 19th century” in part because it overflows with situations in which the ordinary can become extraordinary, and vice-versa. This is at any rate what is captured when observation becomes distracted, detached from a system of obvious perceptions that constitute the usual condition of our lives.

Film, the art of images in movement, is fond of showing these individuals themselves in motion in urban space, and for whom the boundary between insignificant and remarkable gradually blurs as they stroll. The indecision between these opposites lies in a series of constraints sensed by the person, who wishes to escape them. We go walking to “get some air” of course, but here, the expression is literal – throwing oneself into the city’s outside so as not to suffocate within. Distraction is the elusive conveyer of this fragile yet determined desire, seeking emancipation from all that imprisons existence.

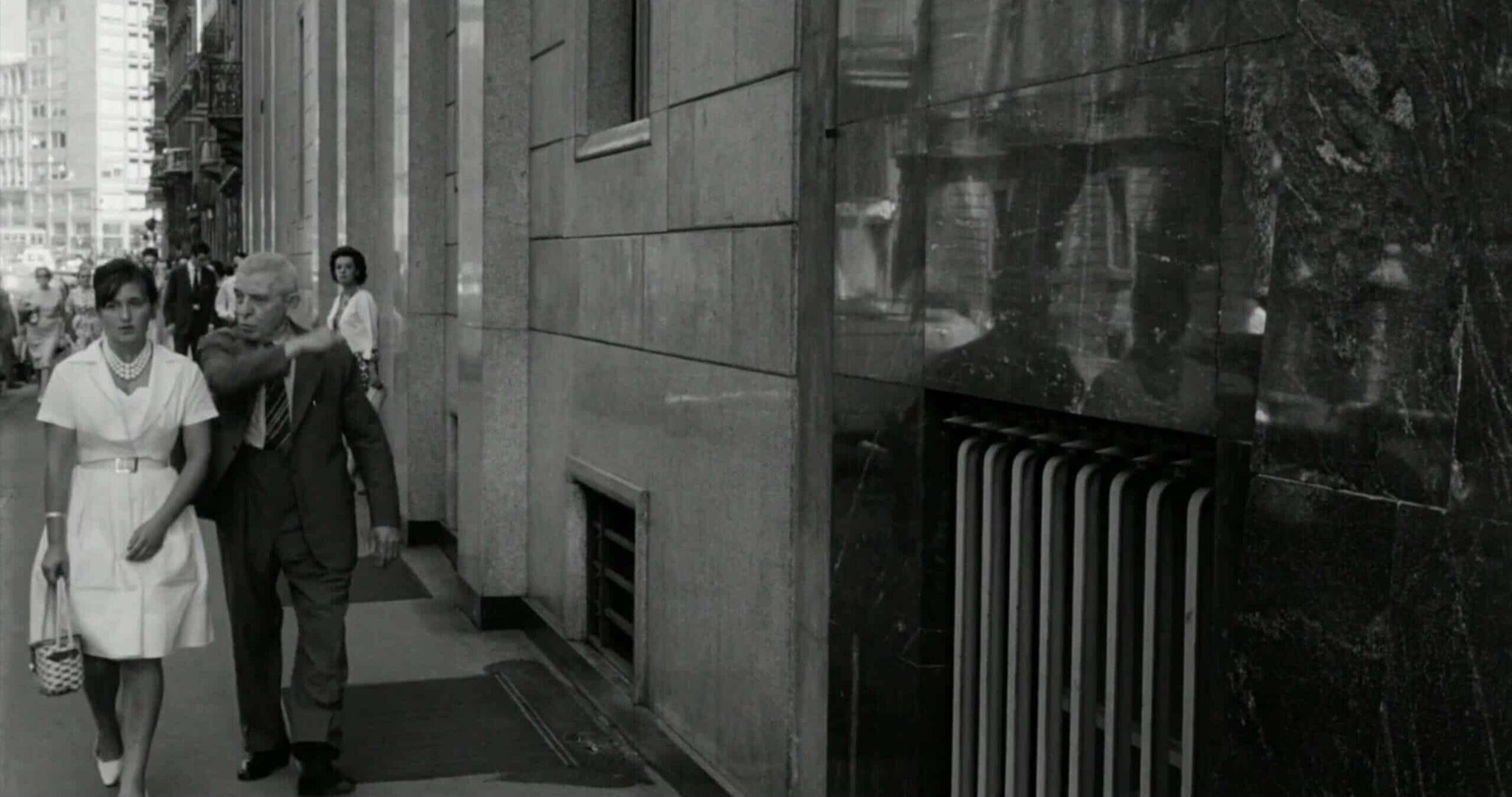

In a phenomenal sequence of La Notte, Michelangelo Antonioni portrays the attempt of Lidia (played by Jeanne Moreau) to free herself from a relationship in tatters, plagued by the social opportunism of her partner (the successful writer Giovanni Pontano, played by Marcello Mastroianni). She abruptly leaves his book launch cocktail, appalled by the self-importance and obsequiousness on display, and find herself plunged into the hubbub of Milan, the modern Italian city par excellence, symbol of the country’s post-war economic miracle. Several shots illustrate a situation that has turned suffocating for Lidia, particularly through images of a city at times resembling a vast prison from which she is trying to escape. The character is seen behind the bars of a building entrance, through the jets of a fountain, or surrounded by the never-ending stream of passers-by indifferent to her presence.

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

This feeling of imprisonment outside is the thinly disguised reflection of the “malady of the emotional life” oppressing her, a “malady” that Antonioni defined during the same period as an affective burden that we inherit at birth, and that has been around since the “age of Homer”, according to him, in total contrast with scientific and technical transformations, marked by constant renewal. The invention or reinvention of the self moves at a much slower pace than scientific and technological progress. The “malady of the emotional life” closely linked with what Antonioni moreover called an “erotic impulse […that is] unhappy, miserable, futile”, not sparing the character of Pontano, or the men that Lidia passes during her wander through Milan. The lecherous looks they throw her way are indeed the sign of a desire for ephemeral conquest to which this inevitably interested “impulse” refers.

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

In a certain way, these looks are the opposite of a distracted observation that, while entailing the pleasure of losing oneself in a bustling atmosphere, doesn’t for a single moment strive to possess what is at the origin of this sensory pleasure (whether arising from a person, object, light, ambiance or more). Distraction traces out lines of flight in the city, or seeks to trace them out, as Antonioni effectively demonstrates in this sequence: it is not easy to escape the forms of alienation accompanying us daily (first and foremost, those of the “malady of emotional life”). It is even quite difficult to dispose of them, as seen in the array of moods overtaking Lidia, wavering between highs and lows – the moments of escape, precisely, in which fleeting joy takes hold at the turn of an intersection, and the comedowns that assail her at the memory of her unhappy existence.

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

Michelangelo Antonioni, La Notte, 1961

The moments of distraction mingle with the moments in which Lidia feels uplifted. They also designate an escape from the self coinciding with a rise in the possibilities that life offers when devoid of “malady”. But these moments are unforeseeable, volatile or ephemeral, and above all, they are uncoordinated among themselves, coming one after another in an order that is itself connected to a walk that unfolds elusively. This explains the utterly singular montage of this sequence, combining the distracted Lidia’s jolting moods, on watch in spite of herself for what might divert her in a stifling environment, within and outside of herself. It also explains how – in a splendid fragment of the film – Antonioni’s camera itself seems to escape the filmmaker and transform into a device for making a documentary, far from the fiction of La Notte. The filmmaker’s work tool no longer seems to belong to him, in the same way that Lidia seeks out a sense of dispossession of herself. Everything plays out as though Antonioni’s camera itself had transformed into a distracted eye – the same eye that Lydia experiences to feel, even fleetingly, an air of freedom that transports her elsewhere.

Dork Zabunyan