I have an obsessive urge to transcribe time, embroidery offers a very potent and interesting form for experimentation.

When time stops as a trauma response,

the only thing left to do is: wait.

A constant state of waiting: waiting to heal,

waiting to digest, to contextualize, and finally to grieve.

Embroidery for me is a way to contextualize, reflect, and deaccelerate the flow of information and trauma.

It provides a potentiality for an art practice that can be comfortable with its specific locality without being entrapped or defined by it.

The appeal of embroidery is multifaceted; it is one of the few mediums that exist, relatively speaking, outside the normative patriarchal power structure. Institutions deem “craft” as a lower form of high culture and unsurprisingly, it is predominately produced by women. The rather site-specific relational aesthetic ecosystem of embroidery gives it relative autonomy and a critical edge. It resists how individuals are taught to see, unlike painting, drawing and sculpture, in which the spectator is always expected to be a man. Embroidery does not cater to this, refreshingly offering a small margin of freedom.

Embroidered motifs and geometry developed in complete harmony with the landscape, trees, seasons, sunlight, social relations, and in intimate relation with the cloth itself, as traditionally, women would embroider their dresses, pillow covers, tablecloth, towels, etc.

One example of the social and emotional significance of embroidery that is particularly striking is how, “when a woman is in mourning or bereavement the dress and the embroidery are dyed deep blue” (Culture and Customs of the Palestinians, Samih K. Farsoun). As time passes and the dress is washed, colors start to reappear slowly, in one of the most poetic representations of grief.

However, this seemingly organic approach to the practice was ruptured in 1948. Palestinian communities were forcibly evicted from their land, and farmers became refugees. In the aftermath of this major trauma, embroidery transitioned to become a symbol of national identity, a collective identity that is under threat and in a state of constant emergency. This meant that the motifs had to be preserved and nostalgia for the lost motherland dealt a blow to the responsiveness of the practice. However, collaborations did take place in refugee camps, as communities from different areas became neighbors and a new community was formed, a community of the stateless. In 1988 in particular, during the first Intifada, under Israeli military occupation, it was forbidden to have a Palestinian flag; women would respond by embroidering the Palestinian flag on the centerpieces of their dresses, turning the cloth into a space of protest, and reclaiming the performativity of embroidery as a responsive practice, rather than remaking motifs from the last moment before time stopped.

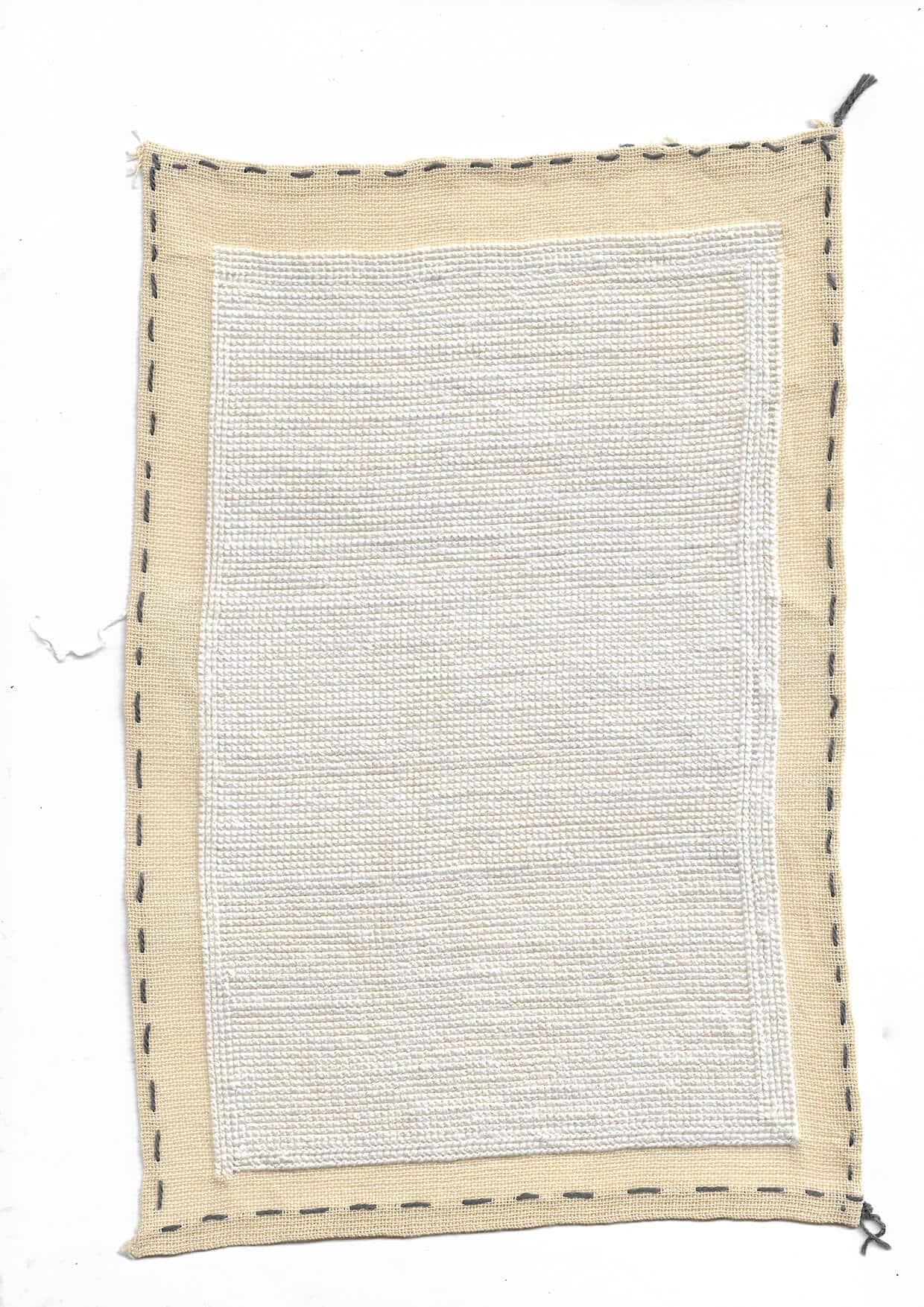

lost track of time, white embroidery, 2020-2021

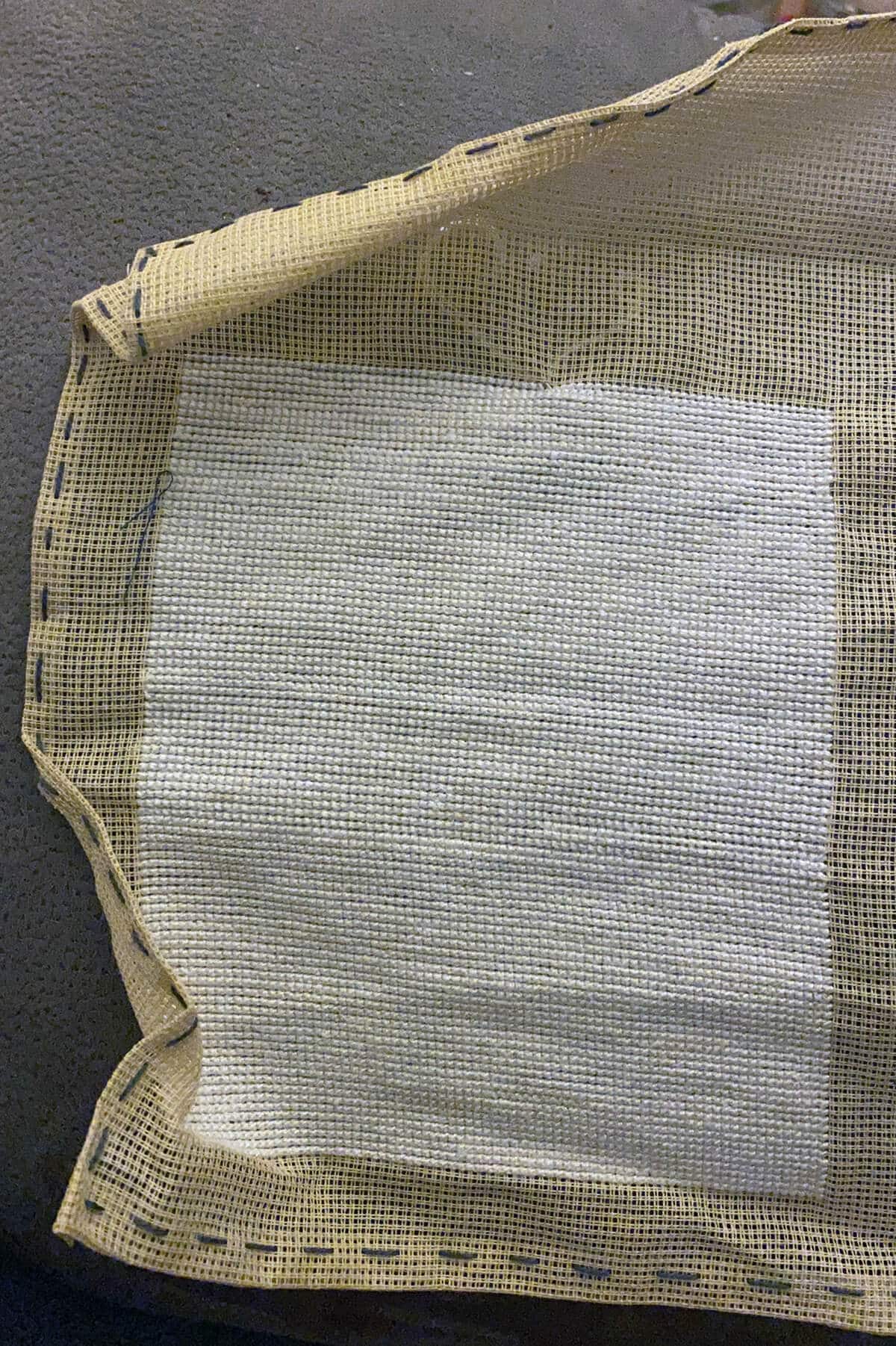

In 2015 I tried to commission a woman to create embroidery for me: I wanted to have white thread embroidered on fabric, but the woman told me she would not do it, adding, “Son, this is a waste of time”. I ended up doing the embroidery myself, which turned into an ongoing series that I am still working on. Stitching repetitively to fill the space of the fabric with white thread, a performance of transcribing time, transcribing a spectrum of intensities. I keep count of how many hours each piece takes to complete.

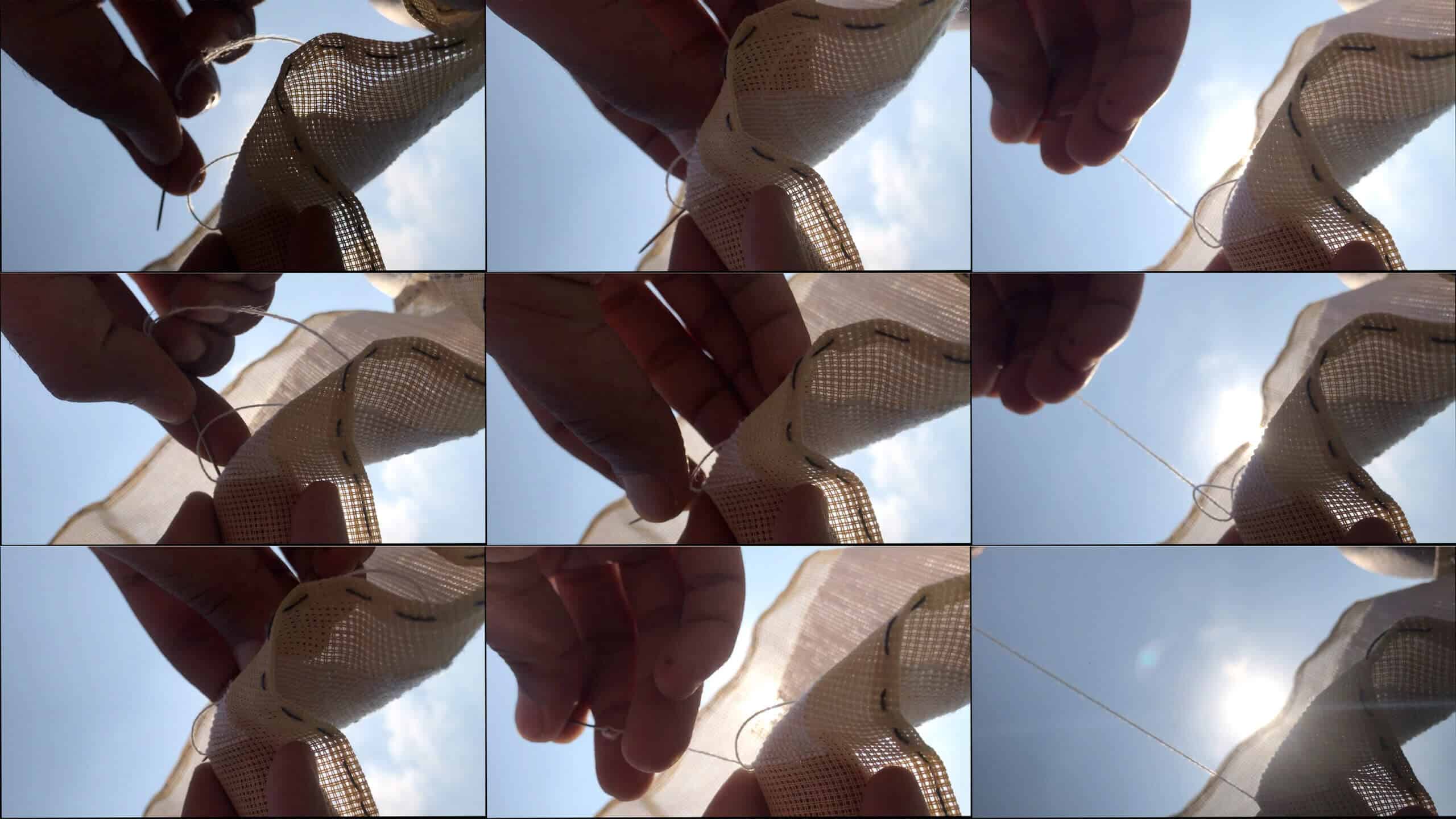

Since the first attempt at embroidering a white square, I have developed this habit of always having white embroidery on me. The repetition and the very act of cross stitching have become an important part of my thinking processes and quite useful when I have to wait for an appointment, meeting, travel…

It has become an essential part of my daily habits, providing me with a safe space, like being in a state of light trance, where you can withdraw from the blackmail of images, news, statements, withdraw but without retreating to a sense of denial, a self-care ritual with a compulsive eagerness to be relevant. How can we distract ourselves while maintaining healthy proximity to society?

In late July – August 2020, as I always do, I was working on white embroidery, this time paying extra attention to the background and how threads are connected.

before blast, end of July 2020.

On August 4, I was at home in Beirut, not too close to port, but close enough to receive fifteen stitches and massive head trauma. In the aftermath of what genuinely felt like the end of the world, there were no bubbles to turn to, every single “bubble” burst at the same time. After the sirens were shut off, there was a nagging echo of horrible silence.

My “safe” go-to when I don’t know what to do is to work on the white embroidery, but I couldn’t. I tried multiple times and it felt genuinely uneasy to do a single stitch, and I gave up eventually.

continue the white on white, November 19th 2020.

The major panic in my head was how to approach this, this “event”, this catastrophe, without projecting, or shouting; I lost my most important tool for thinking. Usually, when I work, I am a spectator, I am close, but not inside the “event”. This was different.

I started working on three embroideries, as I had an urge to use my hands. To do something. Nothing was planned beforehand, I just had the threads and the canvas. And started working on three embroideries of just colors, composition, as abstract as possible. I finished five of them, my wrist was swollen after working nonstop for a few weeks.

I stopped the compositions and finally finished the white embroidery.

Majd Abdel Hamid, January 2021

This letter is the fruit of my discussions with Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez for Palm. The title was coined by Tamara Chalabi when discussing the compositions for the first time in 2020.