If Stéphane Calais attaches a great importance to drawing by hand – for him, everything is decided and begins with drawing – its technical reproducibility, which is now digital, has never been seen by the artist as an existential danger to his own practice. Because the digital world, with the graphic transcription it allows, also remains artisanal, which pieces drawn on paper constantly question and probe in turn. The potentials for expression in a traced-out form are thus multiplied, while, with a few flowers, our visual environment becomes, by extension, a space for a vast experimentation on its formats, media and materials.

— Dork Zabunyan

Multiple desires lead to a simple result: the drawing of a flower in black and white. Perceiving, choosing, re-transcribing, accepting. There is a chunk of something, vegetal, on a piece of paper, on a generally standard, industrially produced sheet. It is a fraction of the world which we doubtlessly want to share, a selected piece perhaps, a section. A fraction.

There has in fact been little analysis done about drawing, the line and its impact on space. Of course, The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting1 and above all Friar Bitter-Melon on Painting2 speak of space and strokes, a definition of the world and of its depiction. Wassily Kandinsky3 was another great teacher about the relationship of marks on the plane of a sheet of paper or a canvas.

By good fortune, I had read Kandinsky long before the Chinese masters because, on finally reading them, I found a confirmation of what I had learned from experience. The precepts of Chinese painting are so clear that they would have robbed me of the pleasure of getting lost for years in the intricacies of graphic re-transcription…

As I have repeated before, drawing is the departure point for most of the things around us: architectures, urbanism, objects, various planes, clothes, etc… Everything has previously been designed and drawn. What we have to deal with are the assorted interpretations of these drawings, their optimal deployment in spaces that are multiplying. Thus, the shift from the drawn to the digital is a question of both points and lines. Of pixels and vectors. We have to accept this change and own it. So that the loss will be minimal, or at least diminished. Of course, this will lack the intrinsic quality of drawing, its versatile and outrageously simple or even simplistic nature, it will instead be a re-transcribed intention, doubled down thanks to various factors, hardware, software. And then communication.

Quite naturally, a great part of technical or commercial drawing, be it for entertainment or not, has joyfully embraced the digital world, thus saving time and gaining in efficiency, but in doing so it has accepted pre-created tools. There is a diversity of drawing techniques because there is a variety of approaches and of viewpoints to be adopted. Just as musical instruments have taken shape during long empirical journeys, the various techniques of re-transcription with lines or colours are quite essential as well as often being quite simple. What of course will change is the interpretation and the way, the manner of transcription. The manner.

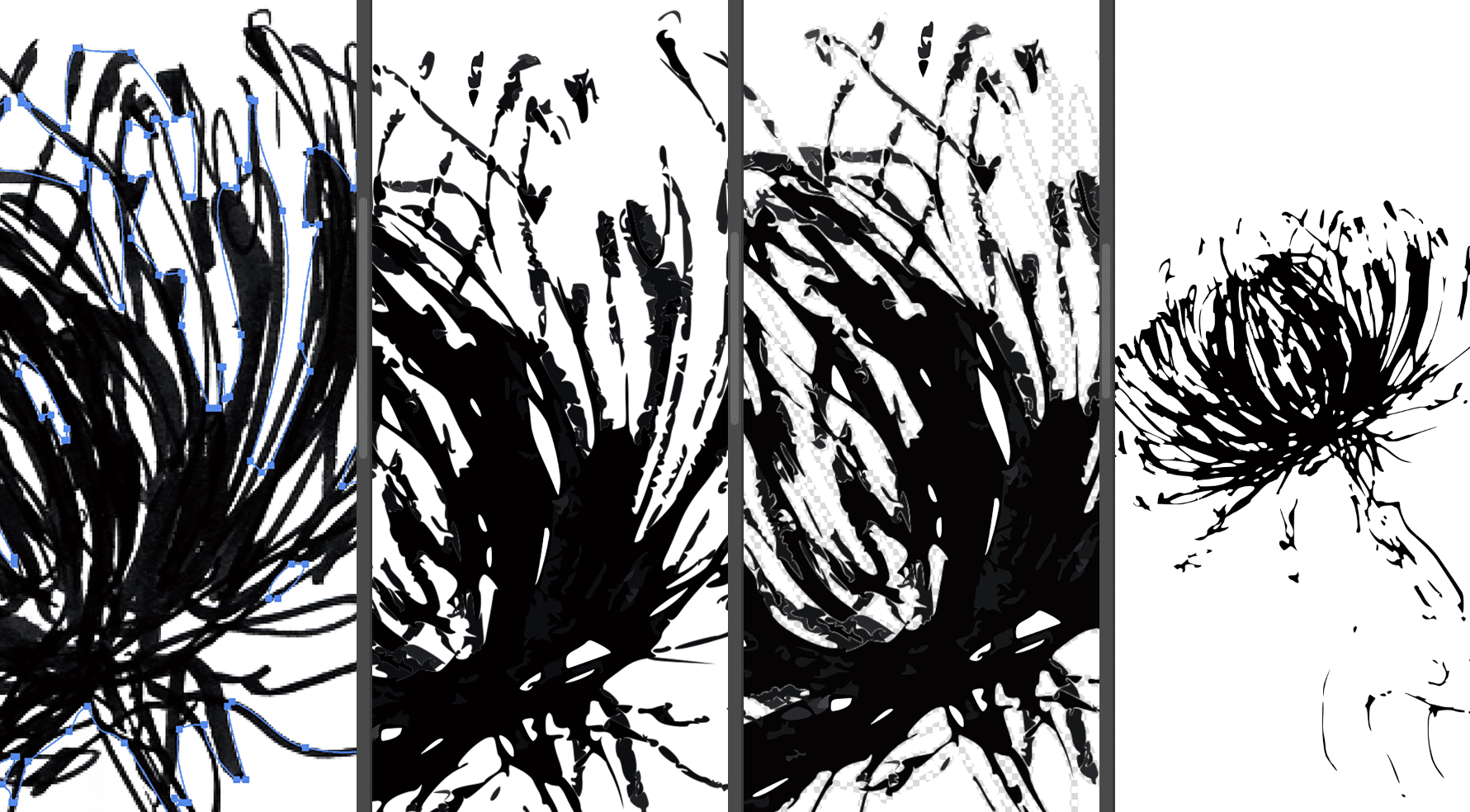

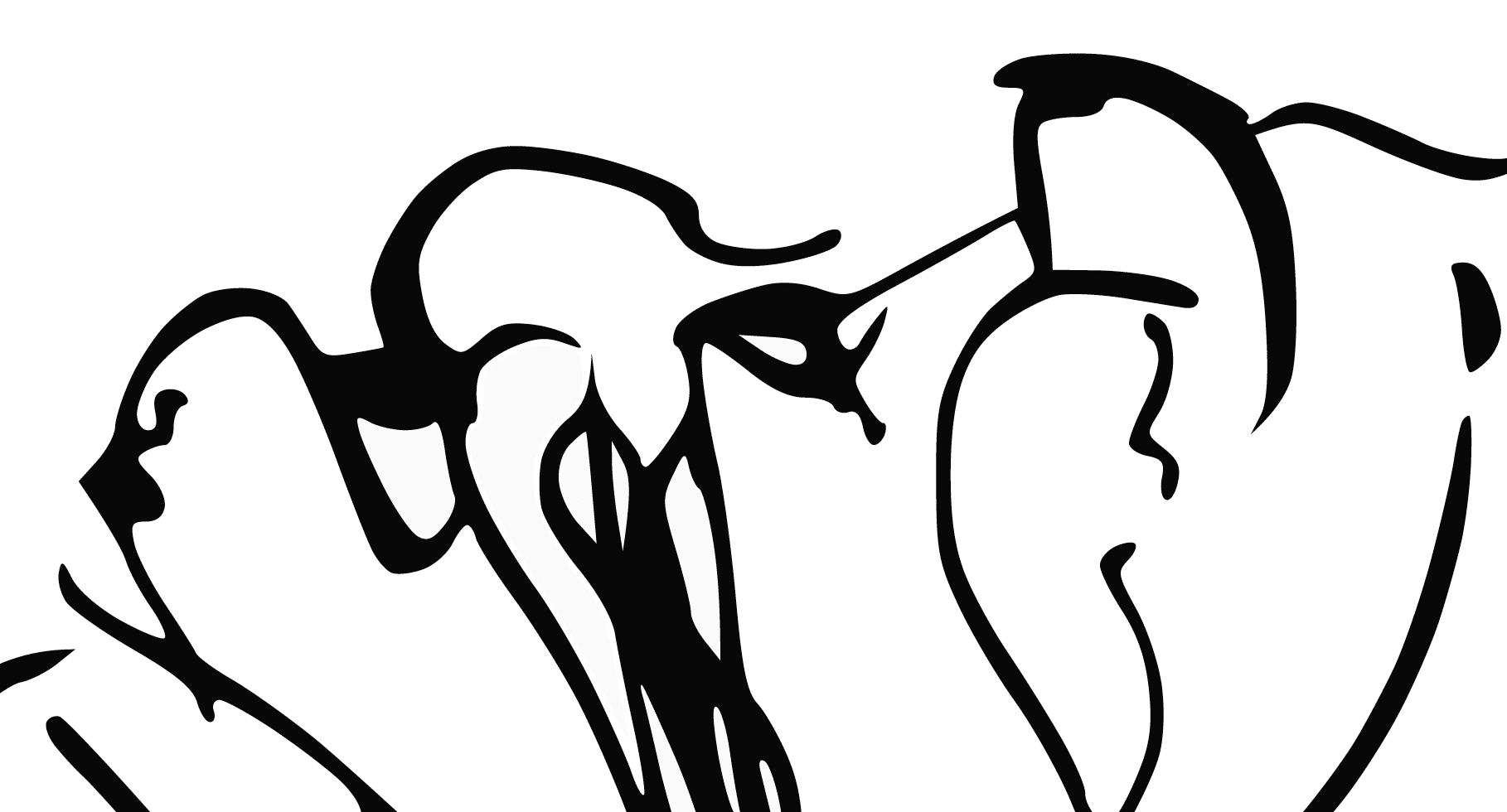

The question being modestly raised here is thus the graphic re-transcription of a fraction of the world: a black-and-white flower. We have shifted drawing from observation to the scanner. Once it has been blown up, the points, the pixels, can be seen. The best way to keep the form of our drawings is thus to transfer them, re-transcribe them using vectors. The interest of this is multiple: keeping the trace of a light, quick drawing, documenting it, but also transforming it into a tool. Vectorisation provides a digital fluidity. Drawing no longer has any particular scale, apart from that of the model. Without a scale, it can thus be set at different sizes, while keeping close to its nature. It then becomes possible to turn it directly into a film for screen-printing and/or to print it onto virtually any medium in any format.

Stéphane Calais, Flower #3 (vectorized detail) © Adagp Paris 2023

Its subsequent journey through networks will then be quite fluid, since it behaves almost like a motif, thus being capable of undergoing any medium, at any size. What will now matter is its unobstructed interaction with the addressee, the spectator, establishing as close as possible a relationship with the addressor’s intention. And if something gets lost in translation, this will then be worked on. All that remains in the end are a few strokes, tools, motifs, objects and memories of a moment in a garden.

Stéphane Calais

Translated by Ian Monk

Bibliographic Notes

1 Anon, Chieh Tzū Yüan Hua Chuan or The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, translated by Mai-Mai Sze, Princeton University Press, Princeton (1997).

It is important here to understand the stones, roots and clouds, the quality of their wrinkles or the nature of pines. The history and manner of each element in a picture, a drawing or a painting are dealt with in a unique way and in a technical manner so as to be able to compose a grand whole. It is above a total manual about space and landscape. To be followed or not followed as befits.

2 Shih-t’ao, Friar Bitter-Melon on Painting, translated by Lin Yutang, Art Society of China, 1976. [This note concerns a French edition: Les propos sur la peinture du moine Citrouille-Amère, commentaires et traduction de Pierre Ryckmans Editions du patrimoine – CMN Plon, 2007.]

I read it when I was about twenty, in a different edition. Pierre Ryckmans has continued his work and his latest version contains more commentaries. I must admit that I didn’t savour all of it at the time. It is an intense, beautiful and infinitely rich work. A book which is more about the mature practician I have now become, for if “a simple puddle conveys a feeling of instantaneity”, “it is necessary, in the harsh and the rough, to seek out a fragmentary image (…)”.

3 Wassily Kandinsky, Point and Line to Plane, translated by Howard Dearstyne, Dover Publications, 1979.

Doubtlessly the work that has most influenced me plastically. A reference work that attempts to analyse what rarely has been: the actions of signs in a two-dimensional space. You can also read it as a technical and virtually scientific desire that seems to come down from the 19th century, a genuine modernity washed up on the beaches of spirituality.