At Federica Chiocchetti's invitation, we are featuring an interview with Patrick Goddard about his film, Animal Antics (2021). This conversation provided an opportunity to discuss current issues around the subject of animals. The character of Whoopsie, the talking-dog protagonist of Goddard's film, is the starting point from which such topics as the tension between anthropomorphism and zoomorphism, and the relationship to animal otherness that is inherent to the human being, can be explored.

Marie Rebecchi

Marie Rebecchi: As you state in an interview1, Animal Antics (2021) is a comedy set in a zoo, at some point in the near future. It follows two protagonists: Sarah, a woman in her mid-twenties, and a talking dog called Whoopsie, who is very proud of her pedigree and doesn’t understand what the wild is. Whoopsie speaks English with Sarah, and thus shares the faculty of verbal communication with humans. Through the figure of this sophisticated talking dog, so distant from all the other animal species she meets during her visit to the zoo with Sarah, what kind of relationship between human and dog did you want to present? Is there a political intention on your part?

Donna Haraway’s Companion Species Manifesto (2003) comes to mind as an example.

In the first few pages of this Manifesto, the feminist philosopher (author of the famous Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s, 1985), declares: “This manifesto explores two questions flowing from this aberration and legacy: 1) how might an ethics and politics committed to the flourishing of significant otherness be learned from taking dog-human relationships seriously; and 2) how might stories about dog-human worlds finally convince brain-damaged US Americans, and maybe other less historically challenged people, that history matters in nature cultures? […] Dogs, in their historical complexity, matter here. Dogs are not an alibi tor other themes; dogs are fleshly material-semiotic presences in the body of technoscience. Dogs are not surrogates for theory; they are not here just to think with. They are here to live with. Partners in the crime of human evolution, they are in the garden from the get-go, wily as Coyote.”

What do you think of these statements?

Patrick Goddard: I actually came to Haraway’s short book halfway through scripting Animal Antics, only as it seemed wrong to not read it, and so it was of limited influence on the scripted characters. My take on dogs and companion species is a little more jaded than Haraway’s (if perhaps, just as fond) although I particularly like the above quotation: “Partners in the crime of human evolution”!

Whoopsie is a pedigree Bichon Frisé. Not a working dog, but yes, a chien de compagnie, although in English we would call this type of dog a “lap dog”; a dog of the right size and temperament to sit in one’s lap. Selectively bred over many generations to be fond-of-being-fondled, cuddled and, as the name suggests, kept to keep the laps of wealthy ladies warm in the dark ages before radiators and underfloor heating. Accordingly, I’m pretty scathing of Haraway’s companion animal “partners” – especially in relation to free will, agency and their general bio-political pre-determinism.

Despite this, in the film, Whoopsie the dog is very much a stand-in for the human; and indeed her own illusion of free will and agency perhaps echoes our own illusions: with the dog’s bio-political pre-determinism in lieu of our own cultural ideologies. At the end of my film, after having disparaged and mocked the zoo animals, Whoopsie (on a leash) is lifted into the boot of a car and put into her own miniature cage.

I have certainly, perhaps in defiance of Haraway’s manifesto, used Whoopsie as a literary device to poke fun at humans. Whoopsie, like humans, views animals as separate, as other, rather than viewing herself as one animal among many. Whoopsie, like humans, doesn’t want her immediate ecosystem contaminated by other species (unless vetted, sanctioned, neutered and documented). Whoopsie, as a certified pedigree, like privileged humans, has paperwork that endorses and validates her in the social order.

Marie Rebecchi: Whoopsie seems to embody some of the most atavistic xenophobic human traits. In looking at otherness (wild animals), the dog, “human all too human”, says: “Lock them up, lock them up”, like Trump’s followers… What kind of influence did John Berger’s book, Why Look at Animals, have on the genesis of your film? Is there an implicit (and ironic) criticism of Walt Disney’s anthropomorphism in Animal Antics? What remains of the animal, of the zoomorphic, in the character of Whoopsie?

Patrick Goddard: Berger’s excellent essay was certainly a major influence in my art practice’s general turn towards the animal a few years before making Animal Antics. Through Why Look at Animals, which is largely about zoos, I saw not only a novel insight into the human-animal relation but also that our relation to animals serves a paradigm for the Spectacle, (anti)Capitalism and notions of the authentic. I mean “paradigm” here as both an example-of but also as a metaphor-for: the zoo animal as spectacle – divorced from their context, stripped of all relations except their status as objects for contemplation, the wild made tame via our very desire to encounter it. The wild as cypher for the uncontrolled or uncommercialized. The “wild” animal as paragon Other.

However, Why Look at Animals, principally thinks on animals as their lived reality rather than only as metaphor for other human conditions. Berger writes: “it is too easy and too evasive to use the zoo (just) as a symbol. The zoo is a demonstration of the relations between man and animals…” My film thinks on the animal in both the blood, and sinew and bone reality, but also a handy metaphor or case study for cognition and thoroughly human socio-political issues.

To quote Berger: “Everywhere animals disappear. In zoos they constitute the living monument to their own disappearance”. The proliferation of animal imagery (cuddly animal toys, cartoon animals and the domestic pet) in our consumer capitalist world, as he notes, became popular “as animals started to be withdrawn from daily life”. In my film the dog character Whoopsie only really relates to any of the animals through pop culture references – a Disney anthropomorphism.

In Animal Antics the animal (though not the dog Whoopsie) is the ultimate Other: unknowable, alien, and either mute or “jabbering” incomprehensibly. Whoopsie – as neo-liberal subject – finds it hard to give value to this “so-called-wild” which sits by definition outside of capitalist relations.

Marie Rebecchi: Animal Antics is set in a zoo, which as you state is a “heterotopia”. A concrete space capable of hosting a certain imaginary: an “espace autre”, as Michel Foucault put it in a lecture in 1967, internal to society but regulated by its own norms (like cemeteries, stadiums, amusement parks). In the case of the zoo, we could say that it is a space of domestication that brings together in one place the different milieux in which wild animals live. In your film, is there an implicit denunciation of zoos as spaces of forced containment for wild animals? Or is your view of this “heterotopia” more detached and non-militant? Indeed, it seems to me that you observe this place in an “earnest” way, presenting the zoo as a metaphor for the current state of contemporary societies…

Patrick Goddard: The film is not “anti-zoo”, but rather mourns a world in which the zoo is the last refuge of the animal. They are fascinating and fun and extremely sad places.

The zoo is a heterotopic container of heterotopias: the audience inhabit a safe, liminal, park-cum-museum that then encompasses the many imitation landscapes and microcosmic environments from around the world. I have my two characters, Sarah and Whoopsie, wander from cage to cage with a contemplative gait, not unlike a viewer in an art gallery: From the plains of Africa, to the bottom of the ocean in a few strides. What they – and all zoo-goers – have come to view, but cannot encounter, is the Wild.

In the film I tried to cram in as many and diverse landscapes as possible, savagely cutting between radically alien environments: an underwater Antarctic penguin enclosure cuts to a misty rain-forest hot house, cutting to miniature insect worlds – the protagonist’s dialogue meanwhile flows unceasingly over the environmental ruptures as if they are having fun with a teleportation device set to random. In this section the characters are detached and disinterested in the enclosures – as if having a chat while flicking through TV channels. The animals and their imitation ecosystems are divorced from their context, signifying nothing other than their own disinterested aesthetic phenomena. In this section of script the pair gaze towards the giraffes:

WHOOPSIE: I love this. Experiencing something a bit real, you know. A bit raw. A primordial encounter… But a safe one! I mean these guys, they’re actually alive. And scary! Very retro… They’re a real bit of living history. Not like the cartoons on the telly.

They’re here, like a freak show from the past. Kept alive in the mausoleum

SARAH: Mew-zee-um

WHOOPSIE: That’s–that’s what I said.

In my mind, Animal Antics operates in three ways. Firstly it is a non-symbolic examination of the animal-human relation and the Anthropocene. Secondly it uses the notion of the Wild as a metaphor for the unknown, the uncontrolled, the outside, and ultimately for the anti-capitalist. Thirdly, building from the other two points, the film uses the animal as cypher for the immigrant and the Other; transposing racist tropes and often animal-derived terminology from right-wing media sources back into a zoological discourse. Gazing at some fish, Whoopsie exclaims, unprompted:

“Now sure, the mammals seem cute – and as you know, I’m a massive fan of meerkats myself – but but when they’re swarming your local leisure centre? And of course that’s just the tip of the ice burg, next you’ll have the birds… and worse!”

Marie Rebecchi:I would like to explore the issue of the human-dog relationship in your film, and more generally in cinema. Jean-Michel Durafour, in his recent article, Pour un chien jaune. Questions de figuration humaine au cinéma (2020), referring in turn to Étienne Souriau’s 1956 article L’univers filmique et l’art animalier, states that there are three ways of depicting the dog in cinema, in a co-evolving relationship with man: anthropological, anthropomorphological and anthropocephalic. The anthropomorphological mode, in particular, differs from any form of anthropomorphism. While the latter forces the animal onto the uniquely human form and procedures (examples are star dogs such as Dingo, Rintintin, Lassie), the anthropomorphological mode goes beyond the distinction between human and non-human, and thinks of human and dog as a single body in transformation (Durafour gives the example of the painted dogs in Lucian Freud, Double Portrait, 1986, or the abused dogs in Kim Ki-duk’s film Suchwiin bulmyeong, 2001).

Whoopsie, too, seems to go beyond a banal anthropomorphism, embodying not only the vices and virtues of human beings, but also constituting with Sarah a common body in the discussion on the language of animals as well as on the relationship of humans with the rest of the non-humans…

Patrick Goddard: Whoopsie was originally conceived of as being a young child and her lines didn’t change a great deal upon her canine transformation. The farcical substitution, in this case, the species switch-up, is a pretty standard comedic and absurdist literary technique to satirize underlying conventions and ideologies that might otherwise go unnoticed. In the case of my film – the fact that Whoopsie the dog doesn’t think of herself as one animal amongst many satirizes a very human species-isolationism. Whoopsie therefore is not an anthropomorphic talking dog, but rather a (if this is a word) canine-o-morphic human.

As you mention, the discussion of language is a reoccurring theme in the film. The first (non-dog) animal language encounter is the “talking” meercats.

Sarah: “They talk but only very very basic stuff. They don’t really ‘speak’…

they don’t really understand what they’re saying they just copy…they’re just trained to sort of…”

Whoopsie: “I flipping love talking animals. I think they should make all animals talk. Simples!”

Sarah: “They’re just parroting what they have been taught is a grammatically correct answer”

The meerkats all claim their name are Eliza, which is both the name of the protagonist from My Fair Lady who is taught how to speak “posh”, and is also the name of the first computer to pass the Turing test – convincing, however briefly, a human counterpart that it was itself a comprehending sentience.

Whooopsie, ironically later parrots Sarah’s opinion to another zoo-goer, however crucially fumbles the grammar to reveal that she too doesn’t really understand the content of what she is saying, and is herself like the meerkat assembling words in an almost passable syntax.

Later in the film Whoopsie proclaims: “They should make the lion speak!” which prompts Sarah to parrot Wittgenstein’s proclamation that if a lion could speak, then we wouldn’t understand it anyway (the dog disagrees, citing The Lion King as an example of a comprehensible lion.) Sarah expounds on the theme that a lion’s points of reference – it biological and cultural life – are so alien to us that even if we shared the same lexicon, meaning would still be lost.

Soon after, in a parody of racist condescension, Whoopsie takes a dislike to the penguins who, while appearing to speak, are unintelligible to Whoopsie: “I can’t understand your jibber-jabber” she angrily yells at them. Mutual comprehension therefore – rather than foreign language – is the benchmark by which the dog grants value to the animals.

</br>

Marie Rebecchi: Over the last ten years, there has been extensive debate in France about the possibility of adopting the point of view of animals to make a common world with them, attempting to rethink our relationship to the living and our inner animality. I am thinking, for example, of Vinciane Despret’s books Que diraient les animaux si… on leur posait les bonnes questions? (2012), Habiter en oiseau (2019) and by Baptiste Morizot, Sur la piste animale (2017). Has this school of thought also influenced your artistic work? Or was your film sparked by a different approach?

Patrick Goddard: My film very much starts from the opposite claim and I drew inspiration from – and dedicated a scene to – the philosopher Thomas Nagel’s essay (originally a lecture) What is it Like to be a Bat?

In this thought experiment about human consciousness, Nagel poses several conundrums posed by cognition and the insolubility of the mind-body problem owing to “facts beyond the reach of human concepts”, the limits of objectivity and reductionism, the “phenomenological features” of subjective experience, the limits of human imagination, and what it means to be a particular, conscious thing.

For Nagel we cannot know what it is like to be a bat – or more specifically: for a bat to be a bat. For while we can imagine hanging upside down, listening to the high pitch squeaks of sonar and eating insects, these phenomenological experiences do not translate to our own human cognition. Experience does not and cannot map across in any meaningful way.

I’m afraid I haven’t read the texts that you mention, but it perhaps sounds like they are searching for a system by which we can ascribe similarity, leading to empathy and therefore a system by which to ascribe value. While an underlying political commitment in my film is the importance of ascribing value to the animal, my central problematization is how might we go about giving value to the alien and that which we cannot understand. I want to know if it is possible to sympathise when empathy is impossible.

Having said this, I did have fun in the film imagining what an animal’s POV might look like: we shot the spider’s POV through a kaleidoscope, the mole rat POV through a giant Fresnel lens magnifying glass, a fish looks up through the distorting surface of the water at the dogs face intently staring back…

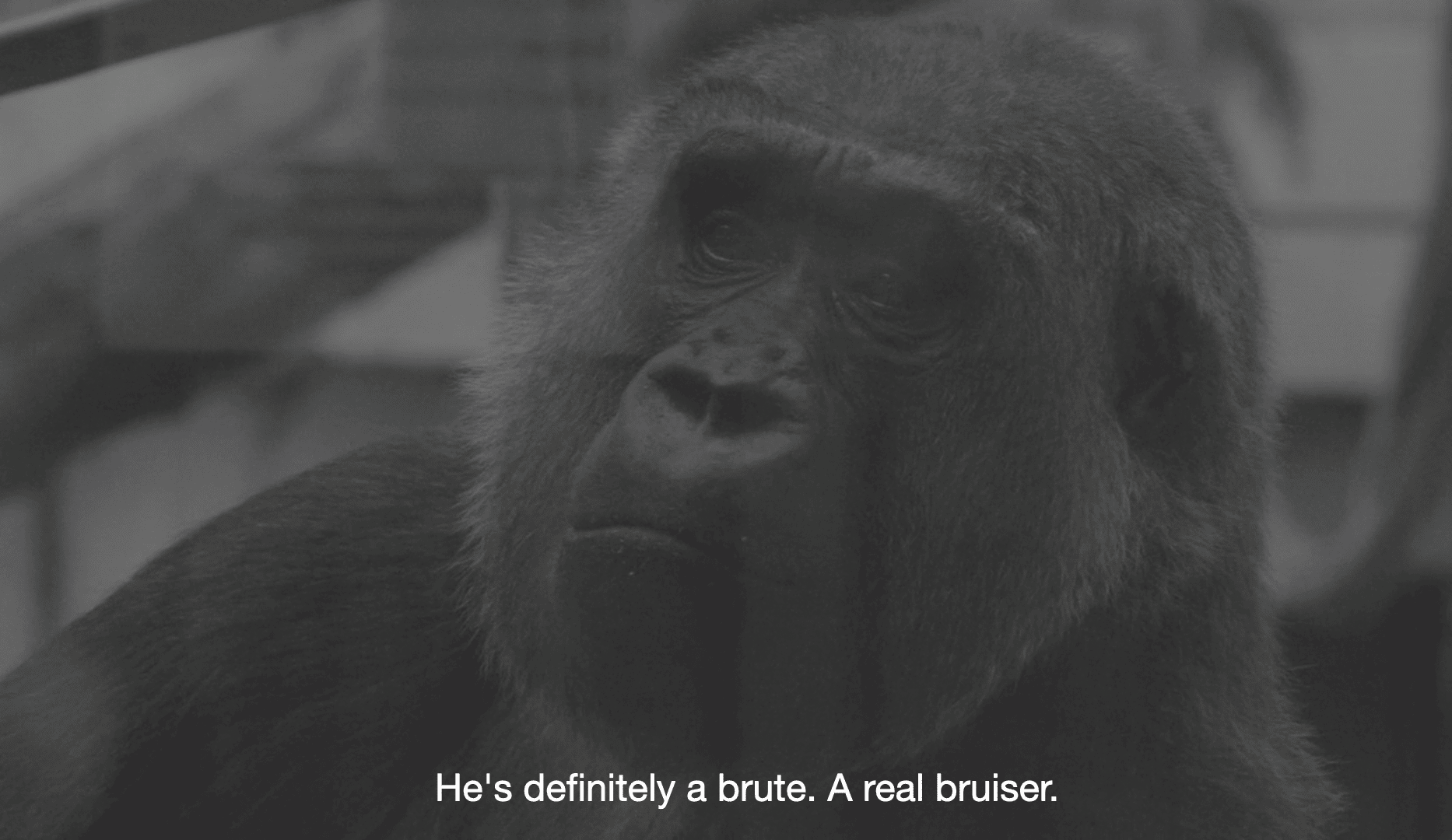

Marie Rebecchi: The film’s space-time is delimited by that of a real walk in the zoo. The use of black and white seems to distance the spectator from a concrete reality, projecting them into an allusive and metaphorical elsewhere. Why did you choose to shoot Animal Antics in black and white?

Patrick Goddard: I found the black and white more melancholic, invoking a nostalgic longing in keeping with my vision of a sad post-wilderness world (or are we already in a post-wilderness world!?)

The black and white is perhaps even guilty of a fetishization of its animal subjects, but that too seemed thematically in accord with the aesthetic agenda of the zoo that prioritizes above all a visual bias (lighting the bats that live in darkness, putting into clear plastic tunnels the beasts that live beneath the ground).

The script of the film is an unapologetic fast-paced comedy – and yet I wanted the rest of the film to be as earnest, classic and beautiful as possible – to counteract the silly slapstick humor with a sense of pathos.