Exhibition views, which illustrate the key moment in the life of an artwork that is the act of displaying it, are part of a broader history – one that Remi Parcollet knows well. A researcher specialized in exhibition history, he notably explores visual records in the artistic and cultural field, as seen in the publication he edited, Photogénie de l’Exposition (Manuella Éditions, 2018), and the numerous articles he has published . For PALM, he is opening a new chapter in his research, focusing on the timeliest issues in professional, and now amateur exhibition views – their virality in the age of social networks.

— Étienne Hatt

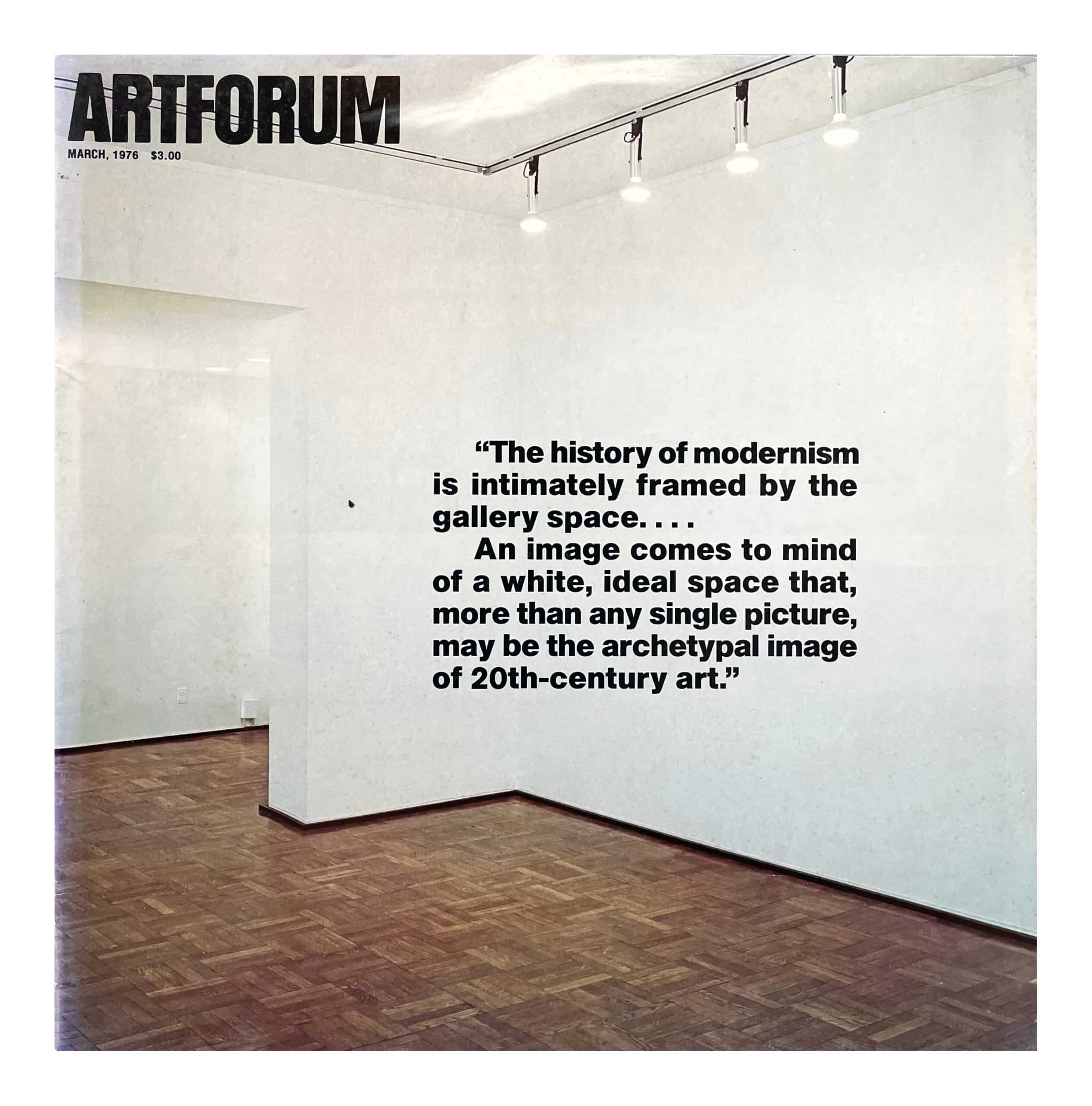

Inside the White Cube, Brian O’Doherty’s publication on the gallery space and its ideology, encompasses three essays published in Artforum en 1976, and a fourth published in 19811. In it, exhibition space is considered a laboratory for art that can no longer be conceived without its relationship to the spectator – which is to say, since this period, that works often only exist upon being exhibited, developing a relationship to a place, time and viewer. In the context shown in Artforum, an American monthly magazine created in 1962, more and more photographs of artworks being exhibited could thus be observed at this time, visual arguments that were certainly more explicit than decontextualized reproductions to accompany critical texts. O’Doherty likely developed his critical analysis based on his own experience in the spatialization of modern artwork; but in some cases, as with the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism, held in New York in 1942, studied in his essay Context as Content2, it was through two exhibition views taken by John Schiff, a shot/reverse shot, that he described and interpreted the ephemeral piece Sixteen Miles of String created by Marcel Duchamp. The perception of the work in its context from then on seemed conditioned by its photographic transcription: “In visual arts there is a history of noticing. Or rather a history of making visible what has been seen but not looked at”3. Brian O’Doherty’s essays are accordingly accompanied by exhibition views that help visualize his reasoning.

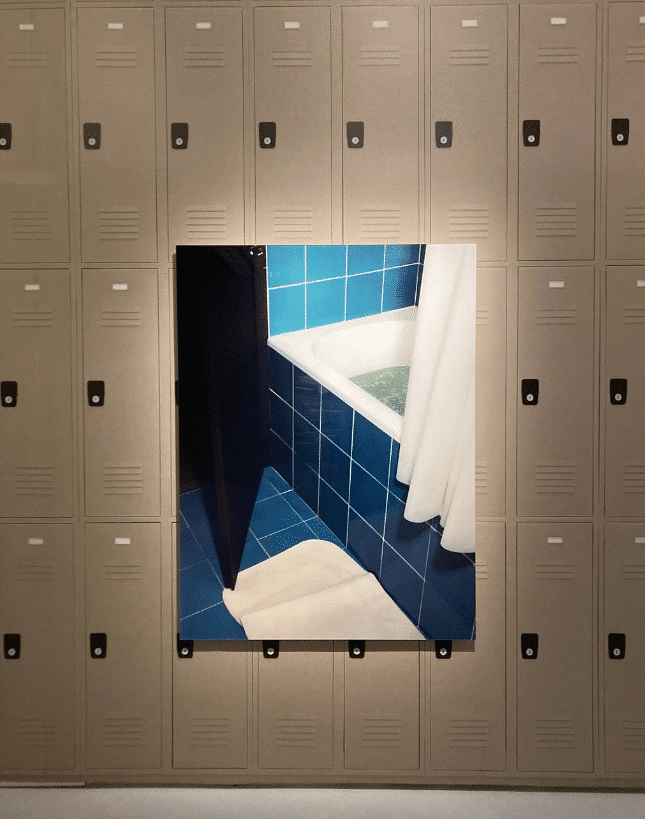

The dissemination of exhibition views, like the photographic reproduction of artworks, was dependent on technical transformations in printing. But starting in the 1850s, salon albums, and the Reports by the Juries from the Great Exhibition of London, inspired by Henry Fox Talbot’s Pencil of Nature, evidence how these views were, right from the outset, produced to be disseminated and shared. Over the 20th century, while these photographs accompanied the development of formats such as postcards and posters, they rarely contributed to the iconography in catalogues, created prior to exhibitions on principle. The dissemination of exhibition views thus developed through the press, highlighting their tendency to serve as both evidence supporting critical discourse, and an image for the purpose of communication. But in the 1960s, the development of artistic practices, and the attention these practices paid to their context of display, led journals to amplify the publication of these photographs and commission photographers to take them. During this period, it was thus already a question of a form of exhibition virtualization. The actual experience of exhibitions has subsequently collided with texts of critical commentary as well as the transformation of exhibitions into images.

Exhibition views have been defined and have transformed based on their dissemination media; but the way in which they circulate on the internet has marked a more decisive change in revealing their full potential for reflexivity. For the past twenty-odd years, galleries and museum institutions have been filling their websites with photographs that they commission or produce themselves, to communicate on their exhibition programming – “visuals” that have become essential elements for press kits. These communication interfaces have gradually been transformed into archives. In parallel, the emergence of digital platforms such as e-flux.com has been observed: launched by artists in 1999, this site relays and gathers announcements from museums, biennials, fairs and magazines like Artforum, Frieze and Afterall. These announcements standardize and systematize the exhibition press release form combining a text and a “visual”. The e-flux.com platform appears as an echo chamber for gallery and museum websites. Its interface has thus in turn become a database, with archives now covering two decades. The aim of the Contemporary Art Daily website, created in 2008, meanwhile, is the daily publication of documentation from one or more exhibitions underway, which subsequently becomes the content of the Contemporary Art Library, a vast contemporary art archive. This phenomenon is even more visible on the MoMA website, with its “Exhibition history” section encompassing views of current exhibitions and communications images, which become instant visual archives.

Once these images are placed online, they circulate without copyright restrictions for the duration of the exhibition and are used by press sites with their credits and the courtesy mention. They thus contribute to the communication undertaken by the exhibition producer, also behind its documentation, in a strategy ultimately similar to picture marketing. Through images of the exhibition, the event’s reception is controlled. For largely economic reasons, journals specialized in art news no longer produce or commission photographs to give their viewpoint and corroborate the critical discourse of articles – while this is what set journals apart in terms of independence and quality, as with Cahiers d’art from the 1930s to the 1960s.

During or after exhibitions, these images circulate on other digital media, sites for free photo sharing via Creative Commons licenses. These resemble atlases or imaginary museums – like Tumblr, allowing users to create a blog; Pinterest, where photos can be pinned onto virtual boards, allowing for interaction with images, creating often formal compositions and reinventing sequences; and Flickr, where professionals and amateurs can distribute their own photos, forming communities. The images produced by galleries and museums are mixed up and combined with those found online, taken by professionals and visitors alike.

The expansion and widespread dissemination of exhibition views on the internet is clearly a consequence of the convergence, in the digital context, of the transformation of amateur photography practice by visitors, and the development of the participatory culture of new media. This situation is in keeping with the historiography of photography, which has always transformed and been studied according to social functions and amateur practices of the medium. It furthermore seems that given their particularities, exhibition views, more than other photographic genres, are symptomatic of contemporary issues around the dissemination and circulation of images on the internet.

This practice consisting of reproducing and reusing exhibition views is clearly asserted with the Instagram app. Combining a photo sharing platform and the principle of a social network, it notably draws inspiration from Tumblr, with users sharing publications by other accounts in their stories. The phenomenon of virality is heightened by the principle of buzz relating to events. Publication and archive platforms like e-flux and Contemporary Art Daily use Instagram to be topical – the latter announcing its view for the future of contemporary art and promoting art via an organized selection of works and exhibitions. In the same way, galleries and museums must necessarily create activity on social networks through the circulation of the exhibition views that they produce. The information virality characterizing social networks even further reveals the potential of these images to interact, and even interfere, with our encounter with artworks. An experience limited to observing its image on Instagram can be substituted for the memory of having visited an exhibition4.

The vast corpus circulating on social media is a combination of professional views produced by independent photographers commissioned by institutions, curators or artists, and amateur photographs. The subjectivity of the other gaze superimposed on our own gaze5 is made more complex, and these different viewpoints are brought face to face by various hashtags. After decades of bans, museums are encouraging the public to not only take photos, but to disseminate them on social media, sometimes even producing dedicated apps to do so. In 2013, the French Réunion des Musées Nationaux funded an app collecting selfies taken by visitors next to the bright, dynamic works on display in the Dynamo exhibition at the Grand Palais. To promote the exhibition, the involvement of the public is more strategic and less commercial than that of a communication agency.

Some exhibitions are now defined by their Instagrammability. Photographing art seems to have become an activity essential to the social network, with #art and #photography among Instagram’s most-used hashtags. Art critic Ben Luke observed in 20196 that exhibition organizers have become aware that the success of an exhibition is increasingly linked to how photogenic it is. Sara Snyder, head of digital strategy at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC, has noted the consequences of what she calls “visual word-of-mouth”. Bringing together site-specific and immersive works, the 2015 Renwick Gallery exhibition Wonder unexpectedly made massive waves on social media, consequently sparking an “Instagram sensation” during its visit. The perceptual phenomenon is effective: as Francis Picabia affirmed over a century ago, to like something, it must first be seen.

Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director of the New Museum in New York, considers that “it’s a test of a good show if it also makes good photos”, but laments the fact that nowadays, some exhibitions are conceived to produce good photos above all. He observes: “it’s the public making the work by photographing it and participating in its distribution through social media. What is presented as fun and free time is a form of collective labor to produce the work of art.” Gioni’s reflection inevitably culminates with a reference to Marcel Duchamp. But when the artist affirmed that he placed as much importance on the person looking at the work as on the person who made the work, he was characterizing this reception as an interpretive act. Photographing an exhibited work and disseminating this image does not necessarily entail a search for meaning or intelligibility; it is more of a practice of appropriation, a social gesture relating to the photographic sharing that results from digital media. The interpretive act appears more clearly with professional photographers commissioned for photo shoots, their transcription guided or validated by the exhibition maker – especially given that the latter anticipates the viewpoints and framings of the displays they have designed. Ultimately, the interpretation of the work takes shape in this already-there view.

As O’Doherty explains: “Everyone wants to have photographs not only to prove but to invent their experience”7. The widespread surge in and virality of amateur photographs on social networks, via smartphones, is an indicator highlighting the role of exhibition photography in the artificial construction of a collective memory. While photographers seek to restore the aura of the works, situating them in the space of the site of their viewing, Instagrammers, getting their images to circulate, place the works in another context – that of social networks, broadening the field of the scenography of perception. The principle of the dissemination and circulation of exhibition views contributes decisively to the regime of displaying contemporary works.

The curator Sohrab Mohebbi, director of SculptureCenter in New York since February 2022, does not conceive of an art world without exhibition views8. They have, according to him, become “the currency of curatorial success”. Considering the exhibition medium as one of photography’s “forefathers”, he draws an analogy between a photographer’s relationship to their subject, and the exhibition’s relationship to its content. Evidently, the correlation between the practice of photography and the act of exhibiting is fully expressed in the digital image and its environment consisting of social networks. Art history research has looked to exhibition views since they began circulating online. Instrumentalized by the institution and curators, exploited by digital media, consumed by audiences, they are definitively no longer transparent9. Exhibition views are not erased for the benefit of what they depict; they question the act of displaying, determine our gaze and the perception of the work. Art history encompasses not only exhibitions, but their reception through the images they produce.

Remi Parcollet

Translated by Sara Heft

1 Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of Gallery Space, University of California Press, 1999.

2 Ibidem, p. 71.

3 Brian O’Doherty, Studio and Cube: On the relationship between where art is made and where art is displayed, Buell Center, 2007, p. 10.

4 Ingrid Luquet-Gad, “Peut-on écrire l’histoire de l’art à partir d’Instagram?”, Les Inrockuptibles, August 31, 2015.

5 Hans Belting, Pour une anthropologie des images, Gallimard, “Le Temps des images”, 2004, p. 18.

6 Ben Luke, “Art in the age of Instagram and the power of going viral”, The Art Newspaper, 27 mars 2019.

7 Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of Gallery Space, op. cit., p. 52.

8 Sohrab Mohebbi, “Caught Watching”, Red Hook Journal, February 2013

https://ccs.bard.edu/redhook/caught-watching/index.html. Also see Mahan Moalemi, “On the Installation Shots of Contemporary Art Exhibitions”, in Seda Yildiz, Thing, Aura, Metadata. A Poem on Making. Exhibition catalogue, the Museum of Contemporary Photography of Ireland, Dublin, 2019.

9 Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Cahiers du Cinéma/Gallimard/Seuil, 1980, p.18.