Sophie Kovel’s A Long Duration of Losses investigates an Algerian cannon, the Baba Merzoug, seized by the French Navy during the invasion of Algiers in 1830 and erected as a lieu de mémoire and war memorial in Brest, where it stands today despite calls for repatriation. As an extension of this exhibition, Kovel convened a panel discussion in February 2023 with KJ Abudu, Nacira Guénif-Souilamas, and Léopold Lambert to discuss, among other themes, the unfinished project of decolonization. The following conversation, presented here in two parts, revisits and expands on that discussion.

— Daniel Levin Becker

Sophie Kovel: Léopold, you’ve written that ideologies enacted by colonialism and imperialism “require not only architecture to implement themselves, but also material symbols to provide a dominant narrative.” Nacira, you describe France’s tendency to deny racism in the name of an egalitarian Republic, and argue that colonial empire was never part of the definition of the French political identity. And KJ has emphasized the ways in which a logic of colonial power lingers in political, social, and economic forms. Maybe we can begin there, with the notion of lingering, to address the intersection of postcolonial memory and patriotic history.

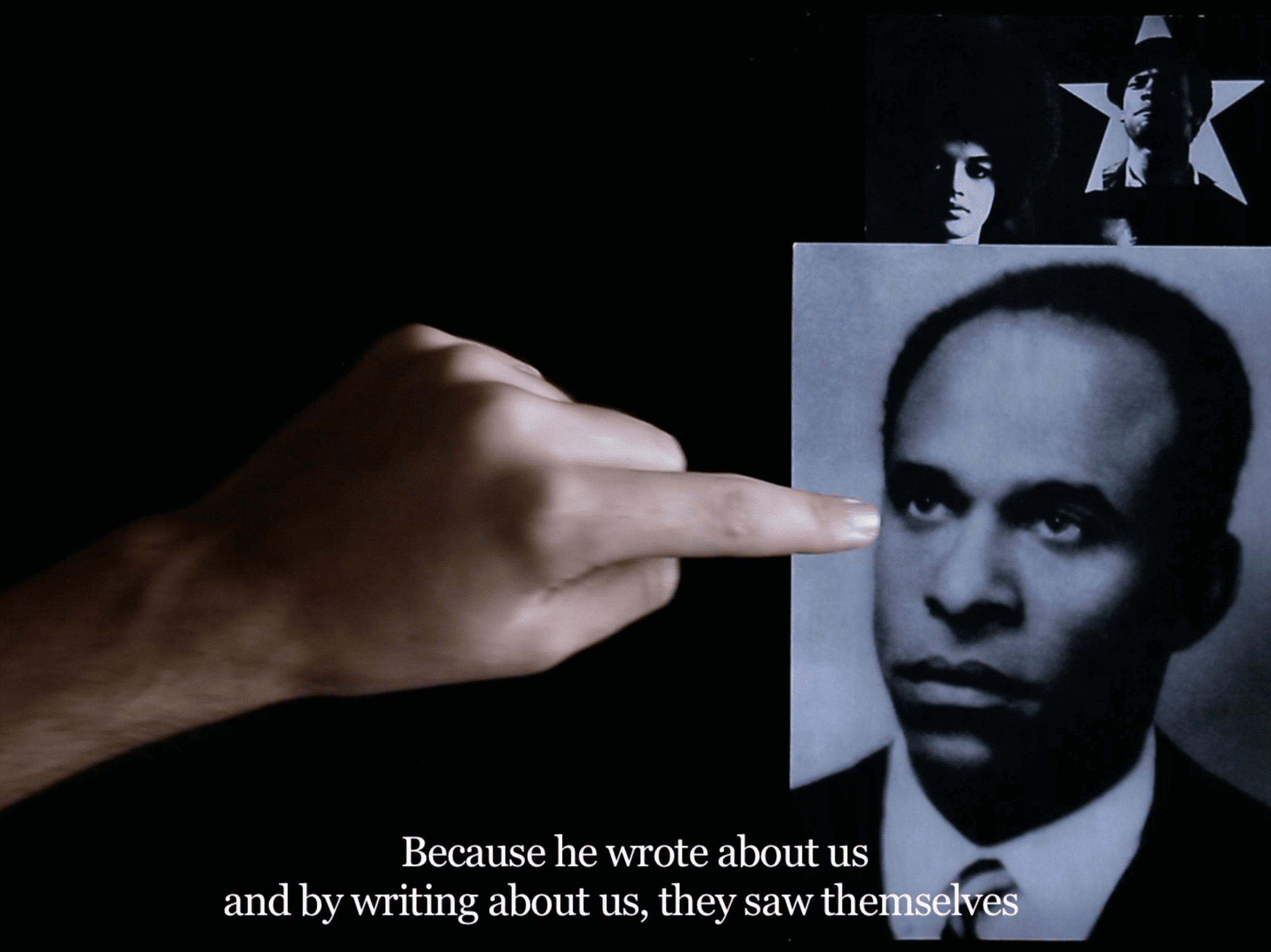

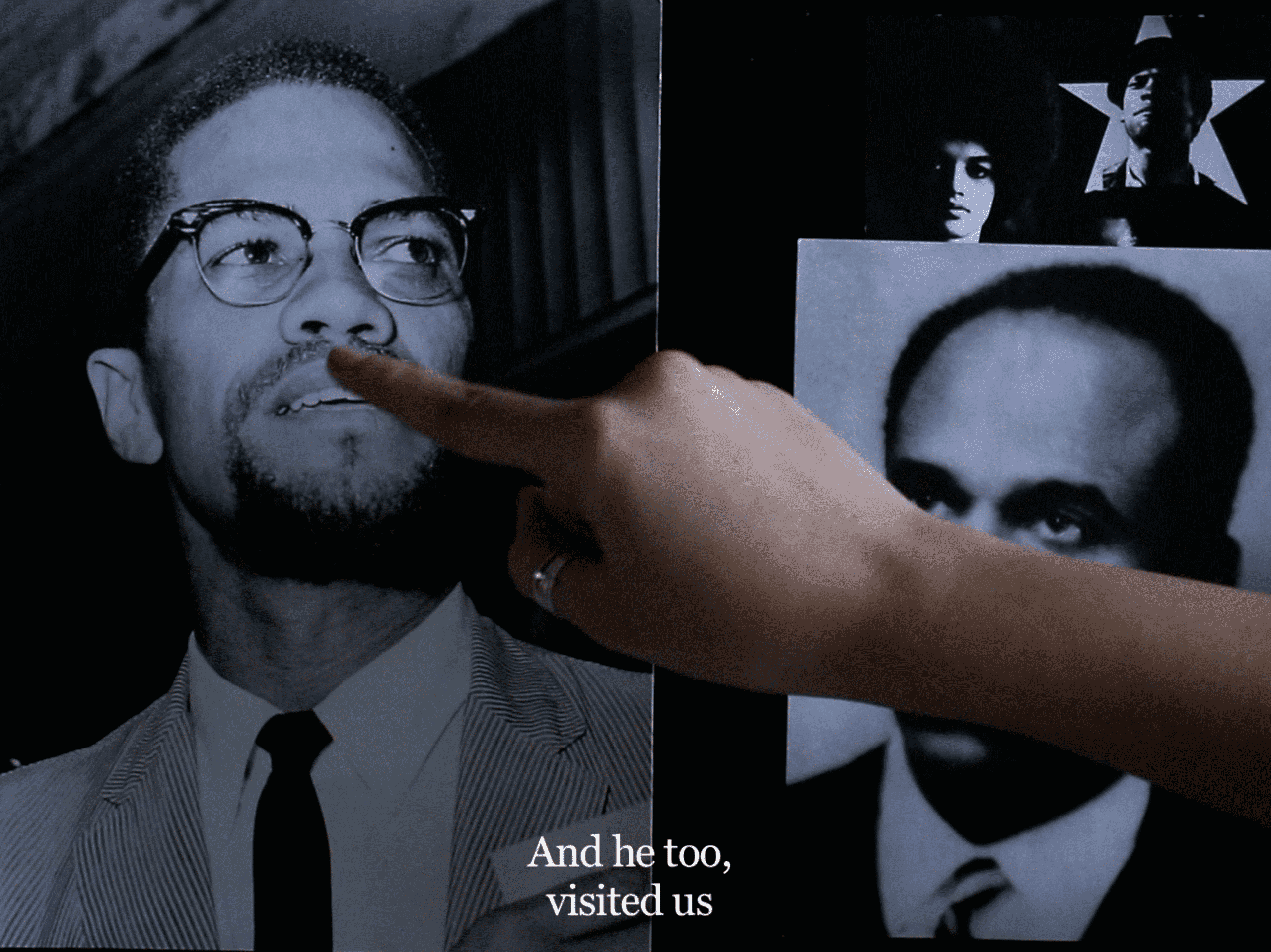

KJ Abudu: My ongoing curatorial project, Living With Ghosts, explores the ways the unresolved traumas of Africa’s colonial past and its incomplete project of decolonization continue to haunt both the African postcolony and the wider world. The exhibition frames the contemporary postcolonial African condition as inherently “hauntological,” to borrow a term coined by Jacques Derrida in Specters of Marx (1994), a portmanteau of haunting and ontology. This metaphor of haunting has proved extremely useful as a framework for thinking about the transhistorical structures and logics birthed by slavery, imperialism, and colonialism.

Ghosts allude to a disturbance or a disordering in the fabric of reality. On one hand, hauntings signal a temporal disjuncture, a return of something from the past, or the future, in the present. On the other hand, hauntological phenomena are spatially disjointed, as ghostly entities are at once there and not there. The specter’s unsettling of spatial and temporal fixity allows us to apprehend the pervasiveness of the coloniality of knowledge, being, and power, as Sylvia Wynter brilliantly elucidates. Wynter describes a register of violence, coming into being from the fifteenth century onward, that is simultaneously so enormous and microphysical that we can’t always point to it, but is nevertheless palpably felt.

Specters transgress and call into question delineations such as presence and absence, the material and the immaterial, as well as past, present, and future. If, as I and others argue, these delineations are products of post-Enlightenment thought, of modernity, then the hauntological bears a strong decolonial charge and potential.

Nacira Guénif-Souilamas: Coloniality, especially viewed from France, isn’t supposed to be connected to modernity, and modernity isn’t supposed to be colonial. But we all know it is. “Colonial modernity” is a tautology, and has to be understood as such. The problem is that colonial modernity isn’t represented. Modernity is very much represented, but colonial modernity is precisely what is obscured most of the time, and it’s a daunting task to make it more visible.

KJ Abudu: It’s an impossible gesture, because our very field of representation comes into being through the process of modernity. We’ve all inherited modernity’s representational tools: its grammars, its forms, its media, its technologies. If the field of representation is the very fabric of modernity, how do you represent something structurally absented from that field?

Nacira Guénif-Souilamas: I’m thinking of colonial modernity as the norm. Wynter defines it as that which is not seen and not supposed to be seen, yet impersonated and embodied and performed rather than explained and viewed in plain sight.

KJ Abudu: Sophie, your exhibition also asks how we might picture that which can’t be pictured, namely what Léopold, among others, calls the colonial continuum. The here–not-hereness of the specter gestures towards a non-positivist spatiality of entanglement and relation, which is crucial for defying nationalist historiographies that overlook the nuanced geographical entanglements produced by and through supranational networks of racial capital.

Many of the works in the first iteration of Living With Ghosts protest presentist and isolationist rituals of colonial amnesia and disavowal. For example, in his essay film Reflecting Memory (2016), Kader Attia interviews surgeons, psychiatrists, musicians, and art historians to discuss the psycho-medical condition of phantom limb syndrome and its conceptual relevance for societies traumatized by war, genocide, and colonization. Other film works consider notions of melancholia and the politics of memory, pushing the documentary form to its representational limits by interweaving colonial bureaucratic documents, visual and sonic archives, haunted architectures, and contemporary witness accounts. This idea of representational limits returns us to the ghost and its “paradoxical presence.” Because ghosts produce a felt disturbance in the filmic fabric, they call into question the very notion of representation and its attendant positivist logics.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Lerole: the struggle of memory against forgetting, 2017. Exhibition view, Kunstinstituut Melly, 2017. Photographer: Aad Hoogendoorn. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut / Hamburg. 100 plaques de bois, 2000 blocs d’argile moulés poings serrés, briques, platines vinyle et enregistrements d’importantes étendues d’eau réparties sur le continent africain et autour, briques de construction usagées, briques d’adobe, briques de sable, sable meuble, poudre d’oxyde rouge et noir, roches, pierres. Dimensions variables.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Lerole: the struggle of memory against forgetting, 2017. Exhibition view, Kunstinstituut Melly, 2017. Photographer: Aad Hoogendoorn. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut / Hamburg. 100 plaques de bois, 2000 blocs d’argile moulés poings serrés, briques, platines vinyle et enregistrements d’importantes étendues d’eau réparties sur le continent africain et autour, briques de construction usagées, briques d’adobe, briques de sable, sable meuble, poudre d’oxyde rouge et noir, roches, pierres. Dimensions variables.

The second iteration of Living With Ghosts displayed works by Bouchra Khalili, Abraham Oghobase, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Cameron Rowland, and Tako Taal, among others, addressing structural continuities of power that precede the establishment of colonial states in Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Situating colonial modernity in a broader timeframe, these works look to the transatlantic slave trade of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries and contend with the seemingly infinite refusals and resistances of the enslaved and those left behind on the continent.

Bopape’s work, Lerole: footnotes (The struggle of memory against forgetting) (2018), operates as a counter-memorial and shrine to the countless Africans who have fought European colonial invasion over the last five centuries. In her installation, scores of wooden blocks with inscribed text detail militant historical encounters with Spanish, Portuguese, British, and Dutch invaders. Haptic ceramic forms, which Bopape made with her closed fists, reference the South African revolutionary Robert Sobukwe, who welcomed political prisoners to Robben Island by grabbing a handful of earth and raising his fist as a gesture of solidarity.

Such individual and collective choreographies of anticolonial resistance are structurally wedded to Torkwase Dyson’s formal geometric abstract compositions, which are based on the improvised self-liberating movements of enslaved Africans in the Americas—from Harriet Tubman hiding in a triangular garret for seven years to Henry Box Brown shipping himself to freedom in a wooden crate, to Black and Brown communities in the U.S. today creating spaces of rest and pleasure in spite of the disciplining and surveilling forces of state- and capital-backed urban planning.

Nacira Guénif-Souilamas: Sophie, I’m thinking of how you describe the erection of Baba Merzoug in Brest as a remnant not only of the conquest of Algeria, but also the way it lingers in distant places such as Nouméa, in Kanaky New Caledonia. What artifacts would we choose to show that today isn’t just about the past? The repatriation of Baba Merzoug, for example, might be a question for the French state—what would the state be willing to do about its current colonial presence? What artifacts would speak to that?

I also wonder, thinking about the artifacts sent back to Algeria two years ago, which power this repatriation benefits. Because the return is also, puzzlingly, a way to acknowledge the legitimacy of a power that’s not seen that way by its own people—as is the case in Algeria right now. The question of repatriating artifacts is inextricable from that of who’s receiving those artifacts, and how they then use them. How are the ceremonies that come along used to reinstate a sense of legitimacy that might otherwise be lost? I’m asking because this will happen again and again in the future.

For example, [Algerian president Abdelmadjid] Tebboune is taking advantage of the fact that negotiations with the French state will reinforce the power of an authoritarian state that already silences the media, opposition, and activists, and crushes the everyday lives of ordinary people. A state using decolonization as a performative gesture rather than a real process with deep consequences for the people meant to benefit from it—just as France has done in Kanaky. What do we do with this trend of repatriation when it comes to states and powers that don’t get along with the sense of freedom their people expect?

To my mind, all exhibitions are about showing something that is in plain sight but unnoticed by the ordinary gaze we all exert. I wonder how this comes into dialogue with the clandestine present comprising the remnants of the past we see in our everyday lives. Of course, Baba Merzoug is a strong expression of this clandestine present, something never deciphered for the inhabitants of Brest. The meaning of this present is never explained: it’s right there, but who is really aware that this artifact came from the conquest of Algeria and, after a long journey, ended up in this section of the city? This is promising in terms of pedagogy, and in terms of showing how ordinary landscapes or cityscapes speak to our past and our present in ways we need to decipher and learn from.

April 2023

KJ Abudu is a critic and curator based between London, Lagos, and New York. Informed by anti/post/de-colonial theory, queer theory, African philosophy, and Black radical thought, his writings and exhibitions focus on critical art and intellectual practices from the Global South (particularly Africa and its diasporas) that respond to the world-historical conditions produced by colonial modernity. KJ Abudu is the editor of Living with Ghosts: A Reader, Pace Publishing, 2022. He will also be curating “Clocking Out: Time Beyond Management” at Artists Space, New York, May 2023, and “Traces of Ecstasy” at the fourth edition of the Lagos Biennial, 2024.

Nacira Guénif-Souilamas is a sociologist and anthropologist, professor at University Paris 8, and member of LEGS (CNRS). She writes on de/post/colonial France and Euramerica, racialized and sexualized post/colonial minorities and bodies, racism, and islamophobia. Her writings include “Rediscovered Faces of Photography” in Bilingual Reader of the 12th Edition of Bamako Encounters – African Biennale of Photography, Streams Of Consciousness – A Concatenation Of Dividuals. Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung ed. (Berlin: Archive Books, 2019).

Sophie Kovel is an artist and writer. Her work examines the economic, social, aesthetic, and ideological operations of racial nationalism. Kovel’s criticism has been published in Artforum, BOMB, Frieze, Spike, and elsewhere, and recent exhibitions include Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Denmark; the Jewish Museum, New York; Jenkins Johnson, New York; University of California; Los Angeles; and Petrine, Paris.

Léopold Lambert is a Paris-based trained architect. He is the founding editor of The Funambulist, a print and online magazine dedicated to the politics of space and bodies, founded in 2015. He is the author of four books examining architecture’s active contribution to colonialism: Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence (2012); Topie Impitoyable: La politique du vêtement, du mur et de la rue (2015); La politique du bulldozer: La ruine palestinienne comme projet israélien (2016); and États d’urgence: Une histoire spatiale du continuum colonial francais (2021).