Maurizio Pellegrini, born in Rome in 1951, worked as a photojournalist from the mid-1970s and through the 1980s, documenting events such as the Iranian revolution and the 1980 Irpinia earthquake. It was at that point he realized that he wasn’t comfortable with portraying people’s suffering. So, when he was asked to work as a photographer at an archaeological cooperative in Abruzzo and Lotta Continua, the newspaper he was working for, changed its identity to Reporter (closing its doors shortly thereafter), Pellegrini chose to switch from photojournalism to archaeology.

After working in various roles, in 1993 he joined the Excavations and Theft Office of the Superintendence of Southern Etruria, set up in 1985 for the purpose of monitoring and curbing clandestine excavations and illicit trafficking. Two years later, Prosecutor Paolo Ferri and General Conforti called Pellegrini and the office manager, Daniela Rizzo, to assist in the Medici investigation, one of the most important trials ever to take place in the art world. It was the start of a long story.

But let’s rewind the tape. On September 13, 1995, Italian Carabinieri from the Cultural Heritage Protection Unit, together with the Swiss Federal Police, raided some warehouses in the Geneva Freeport, registered under a company with the name of Editions Services. There, they found 3,800 ancient artifacts and substantial documentation, comprising letters, notes, Polaroid photos and negatives. These storage units turned out to be owned by the Italian art dealer, Giacomo Medici, who surprisingly had connections with such prestigious institutions as the Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan in New York, and the Ny Carlsberg Gliptoteke in Copenhagen. This seizure led to parallel investigations by Italian police against American antiquarian Robert E. Hecht, as well as Marion True, former curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum, revealing their pivotal role in the trafficking of antiquities. While the story of their downfall is widely known, the role of photography as a key factor in this lengthy investigation is less well known.

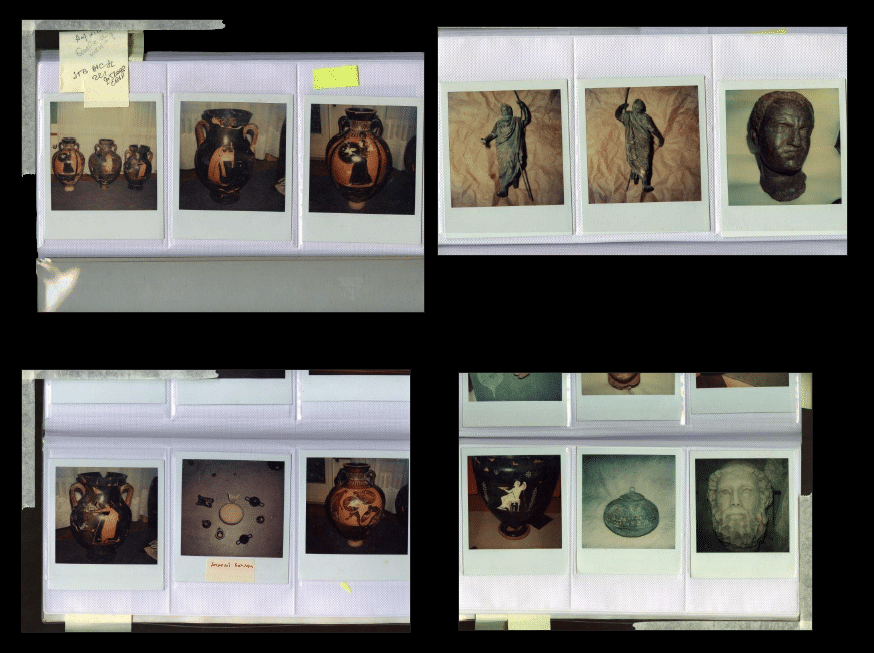

In 1995 Daniela Rizzo and Maurizio Pellegrini were invited to participate in the investigation and were tasked with analyzing the documents, and more specifically, the photographs stored in the warehouses. In fact, together with the pieces, a number of albums containing a large amount of Polaroids showing the artifacts were found during the raid, taken by grave robbers or by Medici himself to show them off to the buyers. Often, these sorts of catalogs displayed the objects as fragments, at the moment of excavation, and then reconstructed, after restoration.

“The use of a Polaroid camera was an important piece of information, because it is a tool that allows photographic prints to be produced without the need for third parties to develop them, so it was often used by traffickers,” Maurizio Pellegrini explained to me during a Skype chat. “Furthermore, the Polaroid as a means of image production allowed us to trace back a great deal of additional information. For example, Polaroids became popular in Italy during the early 1970s, so this allowed us to pinpoint the time period of the excavations pictured. In this regard, many international museums and collectors appealed to the Italian Law on the Protection of Things of Artistic or Historical Interest that was passed in 1939, claiming that the artifacts in their possession came from ancient collections and excavations dating back from before that point. The Polaroids of fragments taken immediately after an archaeological excavation proved otherwise.”

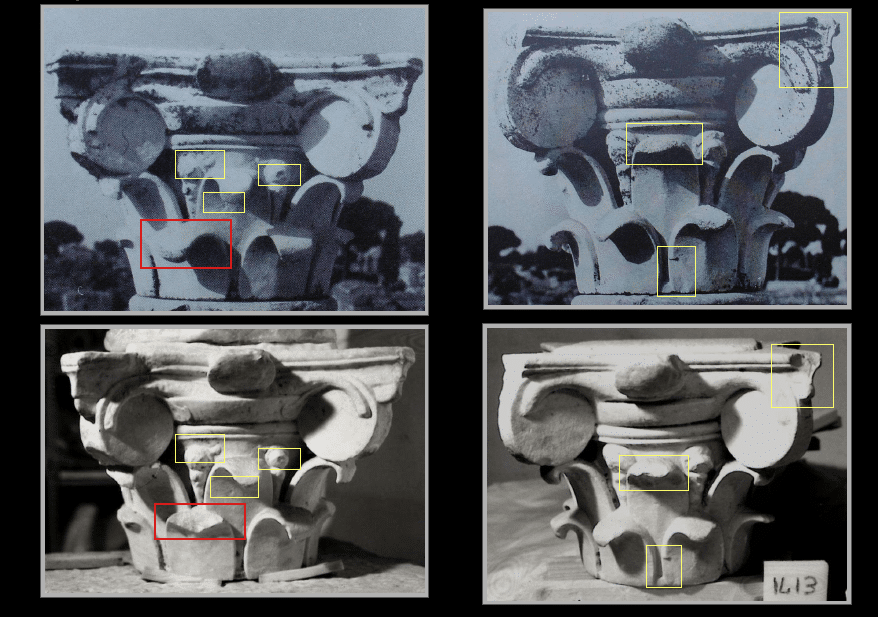

Looking back at this period, one of the highlights of the work undertaken by Pellegrini was the recovery of three capitals. Among the items seized, the Carabinieri identified three capitals found in the Geneva Freeport as potentially being the Capitello of Villa Celimontana and the two Capitelli of “Casa Pesci” of Ancient Ostia, which were reported as stolen. However, upon comparing them with photos predating the theft, the dimensions didn’t appear to be identical, and there were small elements that did not match. “I was convinced they were the same,” recounted the former photographer turned archaeologist, as he showed me the images of the theft report and those taken by the Carabinieri during the raid. “I knew that they had been damaged in a way that made them different and therefore not associable. So I decided to photograph them from the same angle and with the same lighting as in the picture of the theft report. In this way, I was able to detect the similarities between the capitals, as well as the damage that had been done.” For example, with regards to the two capitals of Casa dei Pesci, when comparing the photo taken by Pellegrini with the photo from the theft report, it is clear that intact leaves have been broken, while there are some small imperfections, such as scratches, burns, and nicks, that could not be present in two different capitals. “My past as a photographer has taught me that understanding a photograph means interpreting the photographer’s intention. Therefore, during my career in archeology, being aware of ‘the tricks’ of photographic language has allowed me to identify connections between seemingly different elements. In some cases perspective can distort the shape of objects and make them difficult to identify, just as color dominants can be misleading because the wrong color is perceived,” stated Pellegrini.

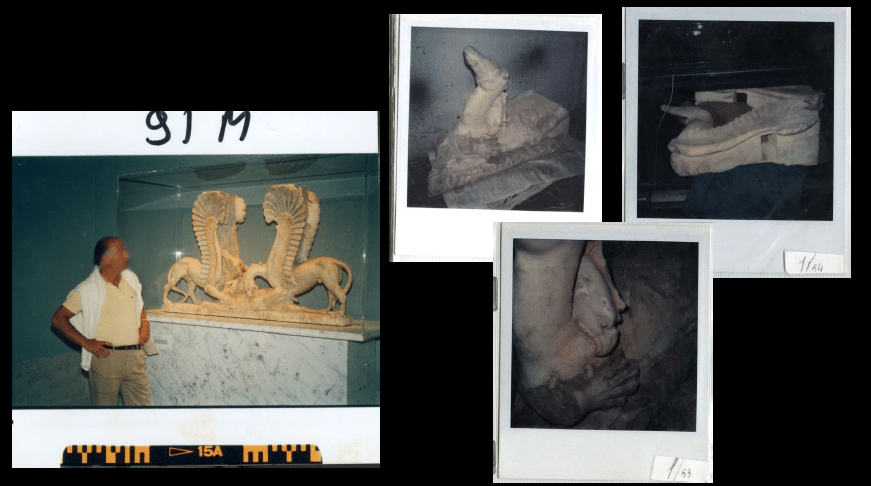

As well as the afore-mentioned Polaroids, the negatives developed by the investigative team were also highly useful to the investigation and crucial to the verdict. “We examined all the photographs that the Italian trafficker had taken during his trips abroad, and in particular those in which he himself, or other well-known figures who had been operating in the illicit market for many years, were pictured next to famous archaeological objects, such as the Euphronius krater at the Metropolitan, the kylix from Onesimos and the Trapezophoros of Ascoli Satriano from the Getty Museum,” explained Pellegrini. “These photographs were found inside undeveloped rolls of film, in among private and personal photographs. We discovered that what might have seemed innocent souvenirs of a nice trip, were in fact evidence of the sales completed by the smuggler who, almost proudly, had had himself photographed next to most of the artifacts he had handled and sold to various American museums.”

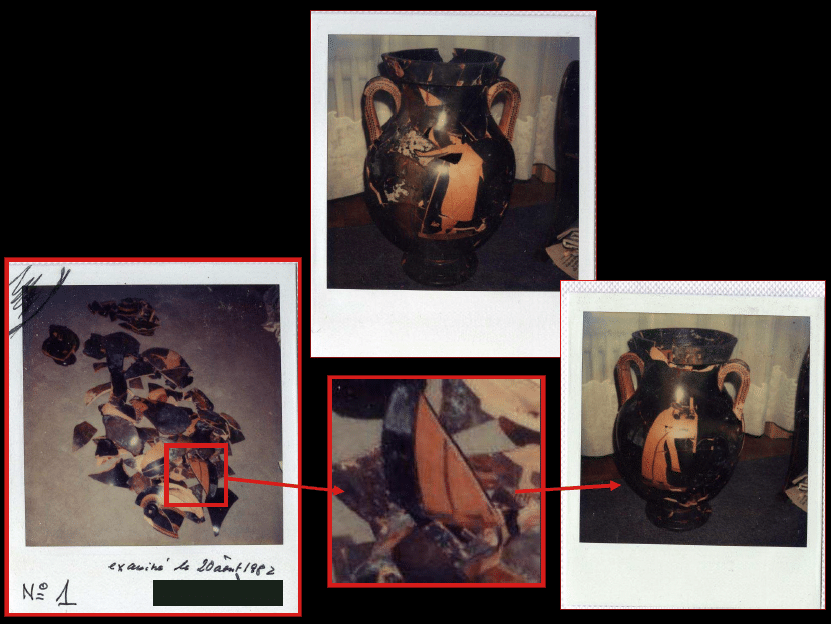

These images were just as important as the Polaroids in unraveling the tangle of antiquities trafficking, including via “reverse” operations, as in the case of the Trapezophoros. “We were intrigued by some photos in which Medici poses next to the Trapezophoros at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, as we were not aware that this had formed part of his dealing. So we scoured through the Polaroids that had been seized in search of something that could prove he had trafficked it. Finally we found some images that showed fragments of the artifact, lying on top of Italian newspapers. That was the evidence.” Thanks to a photo enlargement carried out by Pellegrini, the Carabinieri were able to identify the newspaper, which turned out to be published in Puglia, South Italy, and this subsequently gave rise to the investigation to locate the excavations in the region.

Surprisingly, this led to another major discovery: the identification of an entire set of grave goods from a tomb in Ascoli Satriano, which made it possible to reconstruct the connection between the objects and their context of origin. Pellegrini realized that the Polaroids of the Trapezophoros had the same serial number as those that pictured other pieces; the lekanis and the fragments of two Apulian vases belonging to a group of 21 pieces exhibited in the State Museum of Antiquities in Berlin. Through this reconstruction, based on the same serial number of different Polaroids, it was possible to get real proof that the objects came from the same Apulian tomb. Indeed, the ephemeral medium of the Polaroid assumes that the photographs are produced, if not at that same moment, at least within a short period of time. Despite that irrefutable proof, the group of 21 vases (now 23) are still on display at the State Museum of Antiquities in Berlin, which only recognizes the provenance of the artifacts in part.

These are just a few of the cases within the Medici investigation in which photography has played a decisive role, but they undoubtedly demonstrate how it can serve as a tool in the protection and recovery of works of art and artifacts: among the most significant restitutions achieved thanks to this investigation are the Euphronios Krater, on display since 1972 at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Aphrodite of Morgantina, returned by the Paul Getty Museum in Malibu. Furthermore, in 2004 Giacomo Medici was sentenced to ten years in prison (later reduced to eight) and ordered to pay a fine of 10 million Euros, the largest sentence ever imposed in Italy for antiquities offenses.

Yet, beyond all the successful results of the investigation, this story also teaches us that a photograph cannot constitute an evidence in itself; it is only its interpretation that can refute or corroborate a thesis. “Photography has played a very important role in my work, but I have also always been aware of its precariousness. A photograph cannot be considered a priori an objective document, but must be interpreted and analyzed,” acknowledged Pellegrini. It is no coincidence that art critic John Berger, in one of his enlightening essays, stated that information in itself does not constitute evidence, but rather it is the development of a story that creates meaning.

Today, twenty years after that pioneering investigation, this awareness is even more important considering the crucial issues that new technologies of photographic image production and dissemination give rise to. But the question of the role that photography plays in contemporary archaeology would require much more time to address. For the moment, let’s reflect on how, unexpectedly, Pellegrini’s experience highlighted the curious relationship between photography and archaeology. After all, they both represent physical traces of the past in which we seek the meaning of what has come before us. We traverse them like temporal bridges that allow us to cross the torrent of the unknown, creating connections between who we are, who we have been, and, ultimately, even who we will become.

Rica Cerbarano

Invited by Federica Chiocchetti / photocaptionist