In southern Japan, at the base of the Uto peninsula, inside Sumiyoshi park, near the shrine, there is a monument. The face of the monument is the profile of a bespectacled middle-aged woman wearing a button-down shirt, her gaze tilted slightly upward and into the distance, as if watching over the sea. Below the portrait is inscribed IN MEMORY OF MADAME KATHLEEN MARY DREW, D. Sc. – a British phycologist who died in 1957 at the age of 56, having never set foot in Japan.

From this spot, you can see all the way around the Ariake Sea off the western coast of Kyushu, from Kumamoto to Fukuoka to Saga to Nagasaki. From late October to March, you might also see colorful nets floating by the seaside, or tall poles planted on the shore. This is the harvest season of nori, Japan’s native seaweed.

Nori has been cultivated around the Kikugawa river in Kumamoto since the 19th century Meiji period, when the annual harvest was routinely subject to the whims of nature. The situation was particularly dire after World War II, when food was scarce, and Japanese scientists struggled to comprehend the full life cycle of nori in order to cultivate it more reliably.

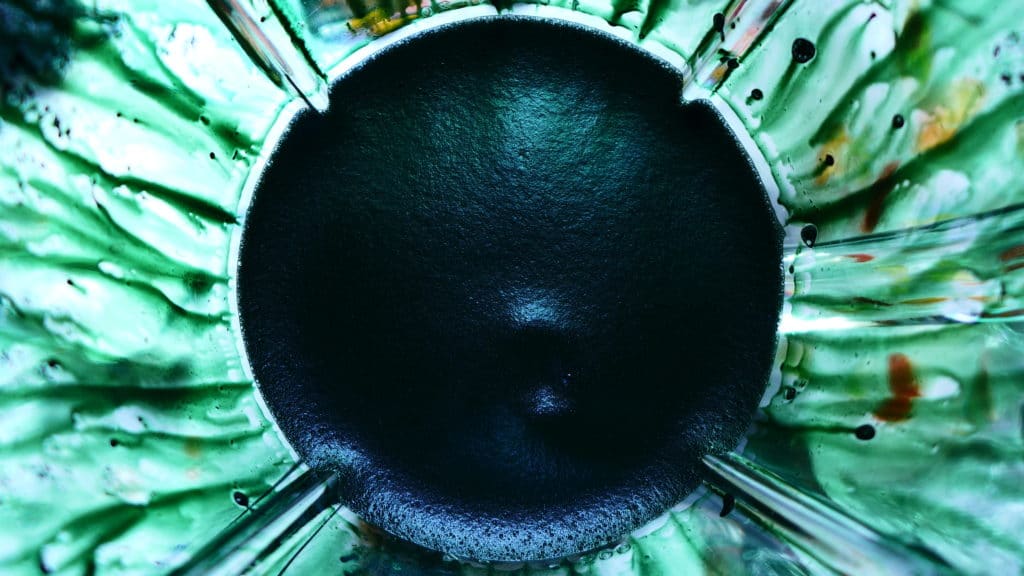

Meanwhile in Manchester, Dr. Kathleen Drew-Baker was meticulously studying European species of red algae, such as Laver. In 1949, she serendipitously discovered that algae filaments nested in seashells during the summer were in fact the same species of algae that matured into the edible seaweed that was regularly harvested in autumn. What if the life cycle of Japanese nori was similar to that of Welsh laver?

Such was the theme of a heated exchange of letters over several years regarding Porphyra (Conchocelis), nori seedlings and oyster shells with Japanese marine botanist Segawa Sokichi. The researcher relayed Drew’s findings to his colleague Fusao Ota in Kumamoto, who finally disseminated the technique among local nori farmers. Within a few years, Ariake Sea nori production significantly rebounded, heralding an industry that would reach its peak in the following decades. The year was 1957.

Since 1963, the monument in Sumiyoshi park commemorates Dr. Kathleen Drew-Baker, who first discovered the missing piece of the nori life cycle. In the region, where nori spores are carefully seeded in oyster shells each summer, she is recognized as the birth mother – umi no oya (生みの親) – of nori aquaculture. Every year on April 14, her contribution is celebrated with a dedicated festival, while a Shinto ceremony honors the British phycologist as a deity. It’s no wonder some interpret her legendary status as umi no oya (海の親) – Mother of the [Ariake] Sea.

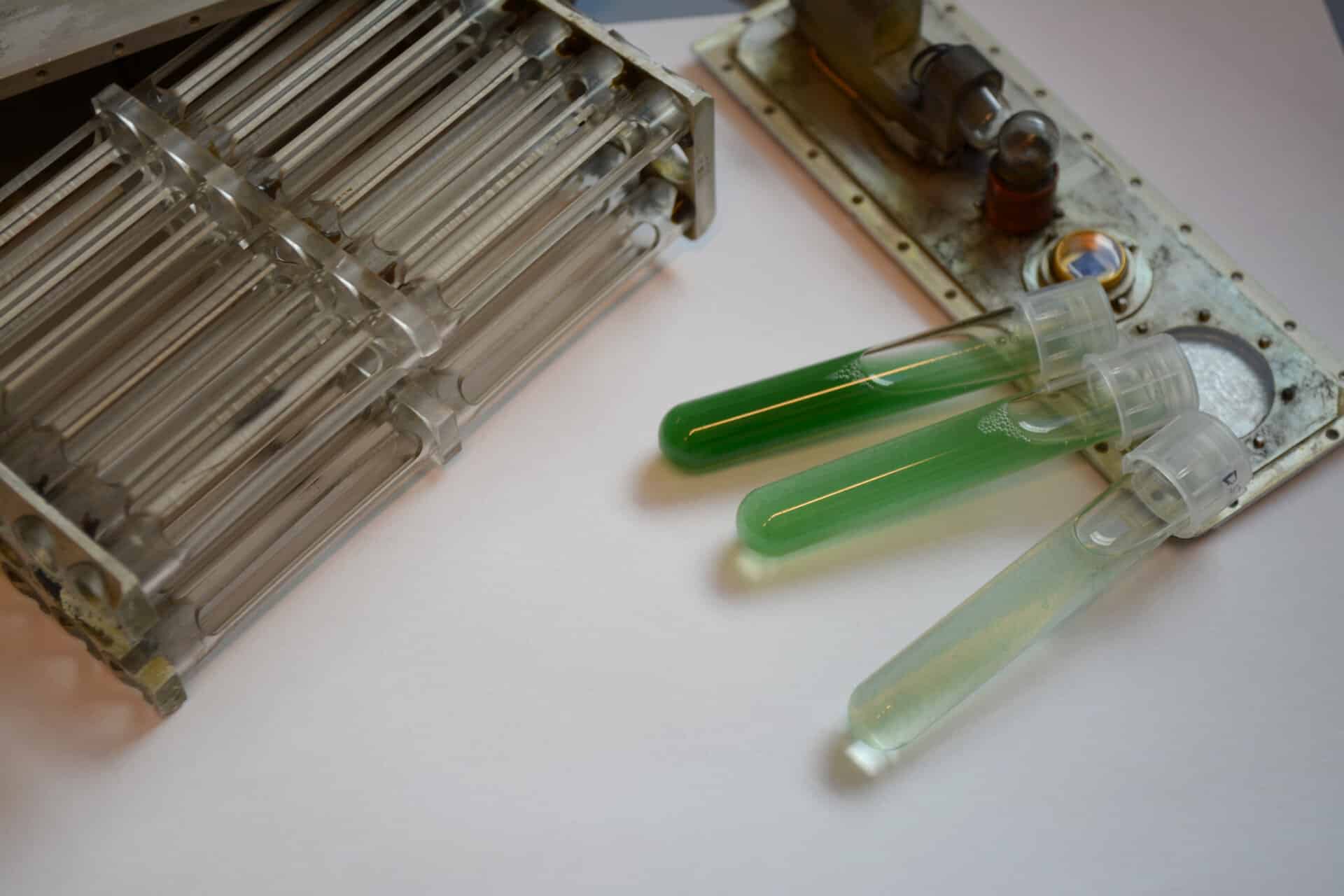

Today, the living memory of this historical series of events is Professor Ota’s assistant and heir, 85-year-old nori researcher Fumiichi Yamamoto. He still works in a makeshift warehouse laboratory just down the road from Sumiyoshi park in Uto, spending eight hours a day looking into a microscope, analyzing the current health of cultivated nori seedlings. The story of the Drew monument is also his story.

Cherise Fong

Umi No Oya / Uto Monogatari is a documentary film by Ewen Chardronnet and Maya Minder, with the support of Antre Peaux, ART2M, DDA Contemporary Art Marseille, ProHelvetia, Embassy of Switzerland Tokyo, Biolab Tokyo, bioart/biomedia platform metaPhorest of Waseda University in Tokyo, PALM ··· Jeu de Paume online magazine, Paris.