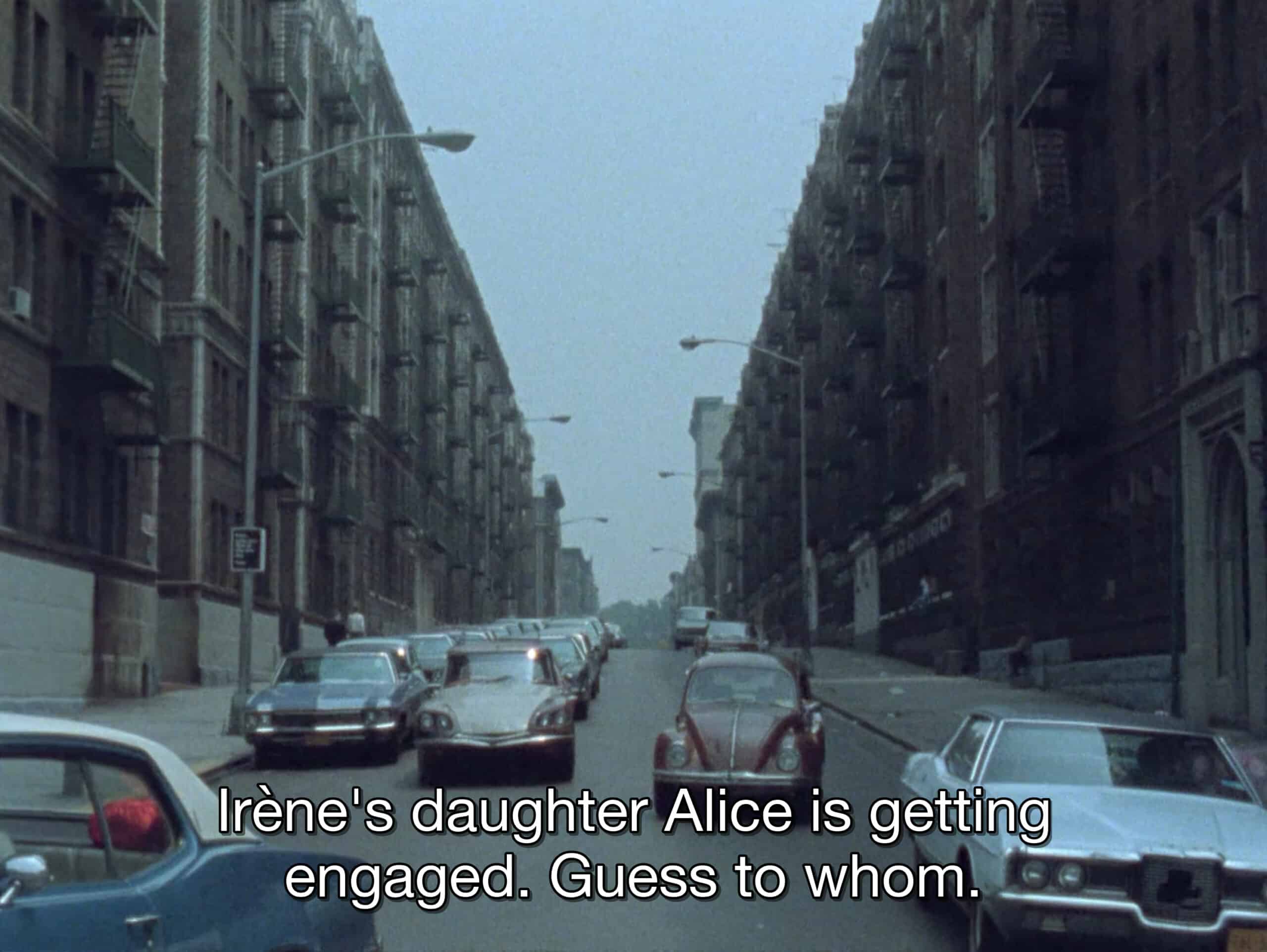

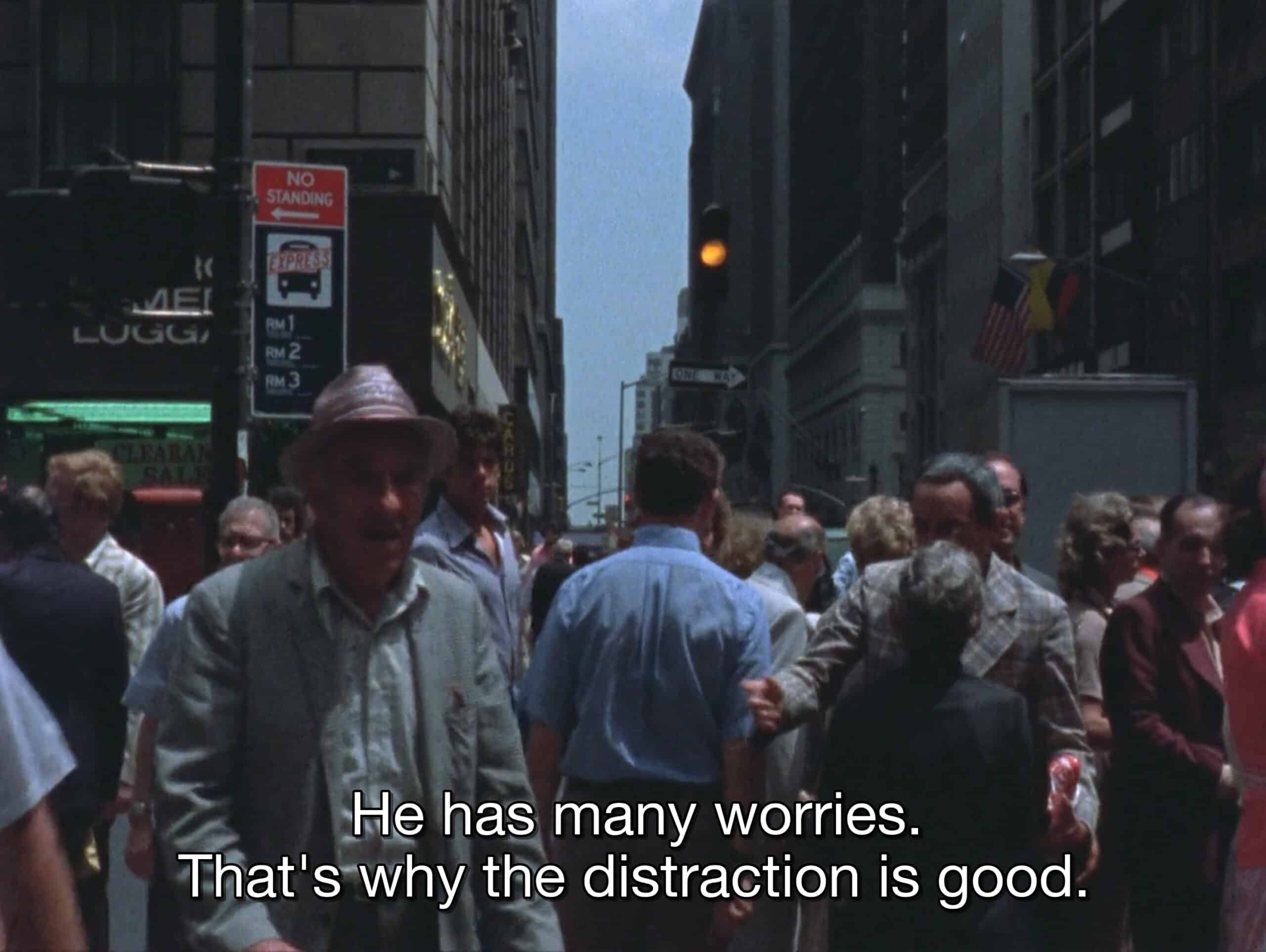

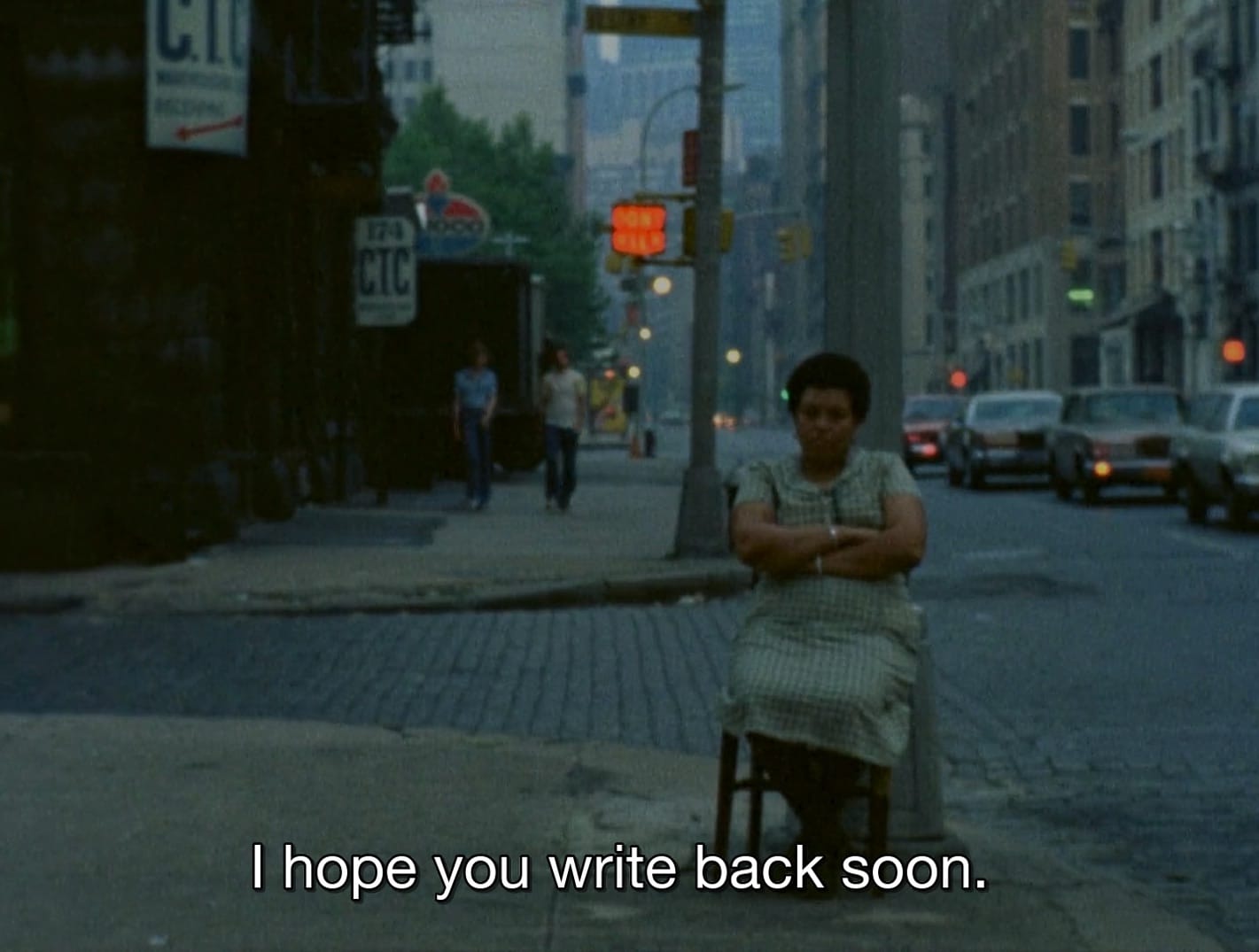

“My darling little girl, I received your letter and I hope that you will continue to write to me often.” When Chantal Akerman begins to read her mother’s letters, the streets of New York have already been passing by for three minutes and forty-six seconds. The action continues in the same vein: on the one hand, this vast foreign city, at times deserted, at times full of life, seen by day, by night and from afar, through long static shots or slow travelling shots; on the other, the voice over which falls silent and then resumes reading, in the same psalmodic tone. Throughout the entire film, not a single letter, the main object of attention, appears on-screen, and as it happens, neither does its sender or recipient, with the latter giving over the leading role to her mother, in a way.

Chantal Akerman, News from Home, Belgium - France, 1976, 16mm, colour, 90 min

Collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman, News from Home, Belgium - France, 1976, 16mm, colour, 90 min

Collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman, News from Home, Belgium - France, 1976, 16mm, colour, 90 min

Collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman, News from Home, Belgium - France, 1976, 16mm, colour, 90 min

Collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman

Chantal Akerman, News from Home, Belgium - France, 1976, 16mm, colour, 90 min

Collections CINEMATEK © Fondation Chantal Akerman

The reason for this absence is simple: “Putting a letter into picture means killing the letter”, states Chantal Akerman in Lettre d’une cineaste (Letter from a Filmmaker), an eight-minute farce made in 1984 featuring Aurore Clément, for the television series Cinéma, cinémas. By not showing the letter, it is therefore spared. Leaving it out of shot thus means keeping it alive. And so goes forth the letter, hidden but free, wandering through Chantal Akerman’s head as she wanders through Manhattan.

The story of this correspondence is already known. In November 1971, Chantal Akerman, at twenty-one years old, suddenly left the family home. Goodbye Brussels and its petit-bourgeois humdrum routine, hello New York, a “Babylon” full of “undefined” and indifferent beings. “I left without saying a thing to anyone, my parents in particular”, she confided into Harry Fischbeck’s microphone in 1977 on the Parlons cinema (Let’s talk about cinema) TV programme, on the occasion of the 30th edition of the Cannes Film Festival, where News from Home was screened in the L’Air du temps section. “When I arrived there, I said to myself that I should write to them often to reassure them”. Evidently, her mother had the same idea. What they write to each other, however, differs in content.

Whilst on the other side of the Atlantic, “in the Americas”, Chantal Akerman feels capable of “doing anything”, at home, life goes on “as usual”. Except that her younger sister has the flu, her father has gained some extra pounds, and her mother is experiencing hot flashes. These trivial reports, a kind of “emotional banality” or tender “padding”, are recounted to us in the everyday words of Natalia Akerman, a Jew of Polish origin, who returned from the hell of the camps before bringing Chantal into the world. Since then, the mother has remained the compass and the muse of her daughter, who draws from the “unfaltering” love that she holds for her, the strength to make her films, and from her humble character, this “refined quality of those who have known suffering”, the raw material of a visceral work. “There’s nothing to say, my mother would say, and it’s on this nothing that I work”, explains Chantal Akerman, whose work reached its conclusion in 2015, with No Home Movie, her last full-length film and final homage to her mother, to this blood tie that cannot be severed by death.

Forty years earlier, in News from Home, already her mother didn’t have anything in particular to say. In her letters she complains, worries, repeats herself. The news she recounts, with a monotonous languor, eventually merges with the weary and dulled hum that is produced by a prolonged stay between four walls. Her well-worn words remain nevertheless words of love. And Chantal Akerman says them as one would say one’s prayers, or in the way that Jeanne Dielman reads to her son Sylvain, on the waxed tablecloth of the dining table, the letter from Aunt Fernande in Canada: softly and without pausing. Sometimes, she speaks so quietly, that the noise of the traffic, the subway, construction work or the seagulls, drowns her out. And thus, the litanies of the mother fade into the background sound, a murmur stifled by the murmur of the city in the background, that the daughter embraces from a distance, as she waits for the homesickness to pass. Regarding these “sounds of real life”, post synchronised on the matte images of Babette Mangolte, bringing to mind a postcard or the bleak scenery of Edward Hopper, Akerman speaks of a “tide”. Because they surge continuously, and the certainty of their arrival echoes the steady flow of the letters, which repeat a “trifling discourse”, inaudible and decidedly futile. Until departure time arrives: a boat casts off from shore, and in the mist, Manhattan disappears in the same way that a civilisation is lost, inexorably.

Thus concludes News from home, filmed in 1976 in 16 mm, a French-Belgian coproduction in collaboration with the INA (National Audiovisual Institute of France) produced on a shoestring budget.

In 1986, Chantal Akerman films another epistolary relationship, that between the American poet Sylvia Plath and her mother Aurélia, from her 18th birthday in 1950, up until her suicide, in 1963. Of their exchanges, a collection remains, published in 1975 under the title Letters Home, adapted for theatre by Rose Leiman Goldemberg, and then by Françoise Merle in front of Chantal Akerman’s camera. Delphine Seyrig plays the mother, her niece Coralie, the daughter, and here the roles are reversed. For it is the mother who rereads the letters of the daughter, “letters to her loved ones”, which this time appear on screen, spread out. In 1987, in the Cahiers du cinema magazine, Antoine de Baecque wrote: “There is such an intensity of gaze in this film, such a desire to exchange words of comfort, and also such intention to bruise, that the images and the sounds, interwoven, become painful.” In its own way, News from Home also causes pain.

Virginie Huet

Translated by Jacqui Chappell