To take the floor, to shout, to exhort, to lecture (or be lectured)… these verbs all capture and express an aspect of speech. Speaking in turn sets in motion a host of different approaches and acts and techniques, turning speech into an object of sorts, launched into our communal space to be passed on from hand to hand, or to fall by the wayside.

All over the world the “occupy” movement demonstrated that when amplification is forbidden and sound systems confiscated, the time-honored technique of the human microphone, or better yet, the people’s microphone, can be used to powerful effect, as was shown during antinuclear demonstrations and the 1999 WTO Seattle protests. We are all familiar with this device: one person speaks and her words — repeated (reproduced, echoed) sentence after sentence, line after line by small groups, — are launched from one end of the crowd to the other.

In this case speech is transmitted not with a microphone or a megaphone but by a series of relays. A technology-free technique depending on the speaking bodies present, it interrogates the voice in terms of its range: amplified, circulated, transmitted, communicated, public-facing and communal-facing, almost anonymous. It is therefore a collective device thanks to which a single softly spoken voice can be heard. A device that slows things down — a guarantee of clarity and intelligibility, a possible development. A device at a remove from the slogan. In order to be able to speak “aloud” without loudspeakers; in order for one’s voice to carry with neither wire nor microphone but through a vibrant chain of comrades and allies propagating the word like a wave; a wave that surges forward, drops and is reactivated by the following line and then the following, till every square inch of space has been covered. It is also, maybe more than anything, a protest technique immediately associated with the occupation — and was indeed used by the Occupy movements to interrupt amplified (official, sanctioned, “dominant”) speech, drowning the loudspeakers out.

Within this dynamic of relaying and launching speech instead of scattering or fragmenting it (relocated, devoid of location), the human microphone delivers, protects and launches speech through a chain of ears and mouths that seamlessly share it. Instead of “exposing” it deposits. The speech of one person finds itself gathered and reactivated by the voice of many, just as each of our lives is deposited in a “social network of hands1”. Deposited, yes, safely placed, remitted to an infinity of voices well pleased to receive this one, the better to protect its vulnerability.

— I was thinking about the pronoun “we” and how it can become the pronoun of a wider connection instead necessarily of identification or affiliation.2 A pronoun that asks not who we are, nor to whom we are similar, nor how many in number, but rather with whom we have agreed to maintain a true connection. And I get the impression that the human microphone brings to life the attractive logic of a vaster, innumerable “we” — a voice that by saying and not saying “I” proclaims all that we might be were we only to connect.

beginning Vth s. B.C.). Paolo Orsi Regional Archaeological Museum of Syracuse.

Another technique, or rather a far older object, comes to mind: the Greek prosopon or the Latin persona, i.e. the theater mask that gave its name to the very idea of the “person” (in grammar as well as in the philosophy of subjectivity3). This also questions the voice and its range. For the mask was also a kind of bullhorn, the ancestor of the microphone or megaphone, used most often in gigantic open-air theaters. I have always been struck (and disappointed) by the fact that this device (and therefore the very notion of a “person”) should be considered only through the prism of vision, of appearing onstage (whether theatrically, or socially), of role composition, of conquering the visible — and naturally more often, of hiding, of simulacrum — when it was also simply a way of amplifying sound, the promise that a written text would be heard.

The history of acoustic techniques has continued to pose these questions, adding to the matter of speech the almost symmetrical matter of recording, the act of encapsulating, capturing, and embedding, since from the beginning of its invention the function of the “microphone” has been both to amplify and to record, and therefore to play back. Maybe speech is always about hoping the voice (no matter how weak) will ring out, will last, will be and remain heard, identical, precise, unchanged no matter the environment.

One often says that one should “give voice” to the voiceless, to the men and women one does not hear enough; we think that we can effectively give voice, as one practices charity, by holding out the microphone or lending an ear, just as one might give spare change to a person in need. But if one thinks that voice is something one “gives,” then it is already too late, it is guaranteed to fail. For speech cannot be given; it can only be noted: it rises up as best it can from wherever it originated; it does not wait for you to prove itself; it is not a question of “giving” it but rather of hearing it, the voice that exists, that one must meet head on and to which one must listen.

If speech remains in essence a “gift,” it might be, in a very different sense, something one gives, brings, lays down between us, something one injects into the world as one does with one’s body, decisions, movements. Not, therefore, in order to return to the “gift of speech” as one does to some kind of privilege some God bequeathed to humankind. But to express the fact that speaking is something one gives, and something one receives when listening to someone speak; a fair exchange in other words.

(I have often felt very embarrassed, even angry, during those public gatherings when speaking time is allotted to the exiled during an exile-themed event mostly featuring other speakers — mostly of a different skin color than the exiles. These moments tend generically to be presented as “personal testimonies” and not as an expression of thought. The speakers are brought onstage in the expectation of stories the sequences and coordinates of which we are sure to be familiar with. We expect nothing other than the story of the crossing, the path of exile. Voice is thus denied at the very moment it is given. We refrain from interrupting, from reacting; we let the voice wash over us — even, for example, when we cannot really hear what is being said or cannot understand it — certain that these stories are all interchangeable. If one does not interrupt once the floor is given, it is because one is in fact certain that there is nothing much to be learned from listening; one does not interrupt a person that one does not consider a true interlocutor; one lets them speak, without any possibility of discussion, and this in turn simply allows shock to expand.)

“We took the floor like we took the Bastille,” Michel de Certeau wrote4 as early as June 1968 when recounting the “events of May.” For the author of La Fable mystique — a professor, scrupulous historian, and Jesuit in no way predestined to feeling “connected” to the youth of 1968 — that revolution and the emergence of a need for language that reflected life as it was lived had real value. He was less interested in activist speech, in the strong, self-assured voices of the spokespeople. He did not wish to embrace counter-power speech, alternative power, an injunction. Nor identity-based speech (the advocacy movement of saying, clawing one’s way out of anonymity, conquering visibility with the aim of mattering). No, taking the floor was simpler, and different politically. Not for recognition, but rather for life itself: the advent, through this or that person, through anybody, of a living voice of the self, of one’s experience of the world, of the life one leads and the life of one’s dreams. A “fierce,” “irrepressible,” fragile, chaotic, surprising voice. A voice that breaks through the muffled sound of the solitudes.

He was also emphasizing the quickness with which that voice was seized, confiscated, discouraged, stifled: covered by political parties and unions for example, buried under the mass of quickly accumulated writings. This was the case for the events of May 1968, but it was also true of the Gilets Jaunes movement, and remains so whenever the question of women’s rights returns to the fore.

Certeau however wished to assert that this “taking” of the floor was in fact impossible, and to remind us of the joy that there was in speaking, in being a person with a voice. That joy is unforgettable, and in its aftermath “living while stifling one’s speech won’t be considered living anymore.” No, the movement thanks to which speech, uttered with a voice and a body and the desire to say something and place it in the hands of others and allow it to live in the public space — that movement could never be repossessed.

In this instance one’s voice is almost analogous to living, to being alive (I would add a “living and breathing creature”) and not just the consumer of a frozen existence. One takes the floor to “be alive and to know it” (words Alain Cavalier used as the title of one of his most moving films.)

I remember my one and only (but oh so memorable) visit to Montreal’s Musée d’art contemporain in 2010. I had arrived the day before. It was still cold, and in the frozen port boats were stuck in the ice, but the snow that had covered the city all winter had begun to melt, and gullies of dirty water ran down the streets from the Mont-Royal Park.

I arrived early. The “Underground City” had left me cold. In the empty museum (it was Easter) a two-part Sophie Calle exhibition was underway: For the first and the last time51. I began my visit with a series entitled La dernière image. Sophie Calle went to Istanbul, where she interacted with blind people. Most of them had lost their sight suddenly, so she asked them to describe the last images they remembered seeing. The portrait of each blind person was accompanied by a text: the description of that person’s “last image,” an image they could no longer see.

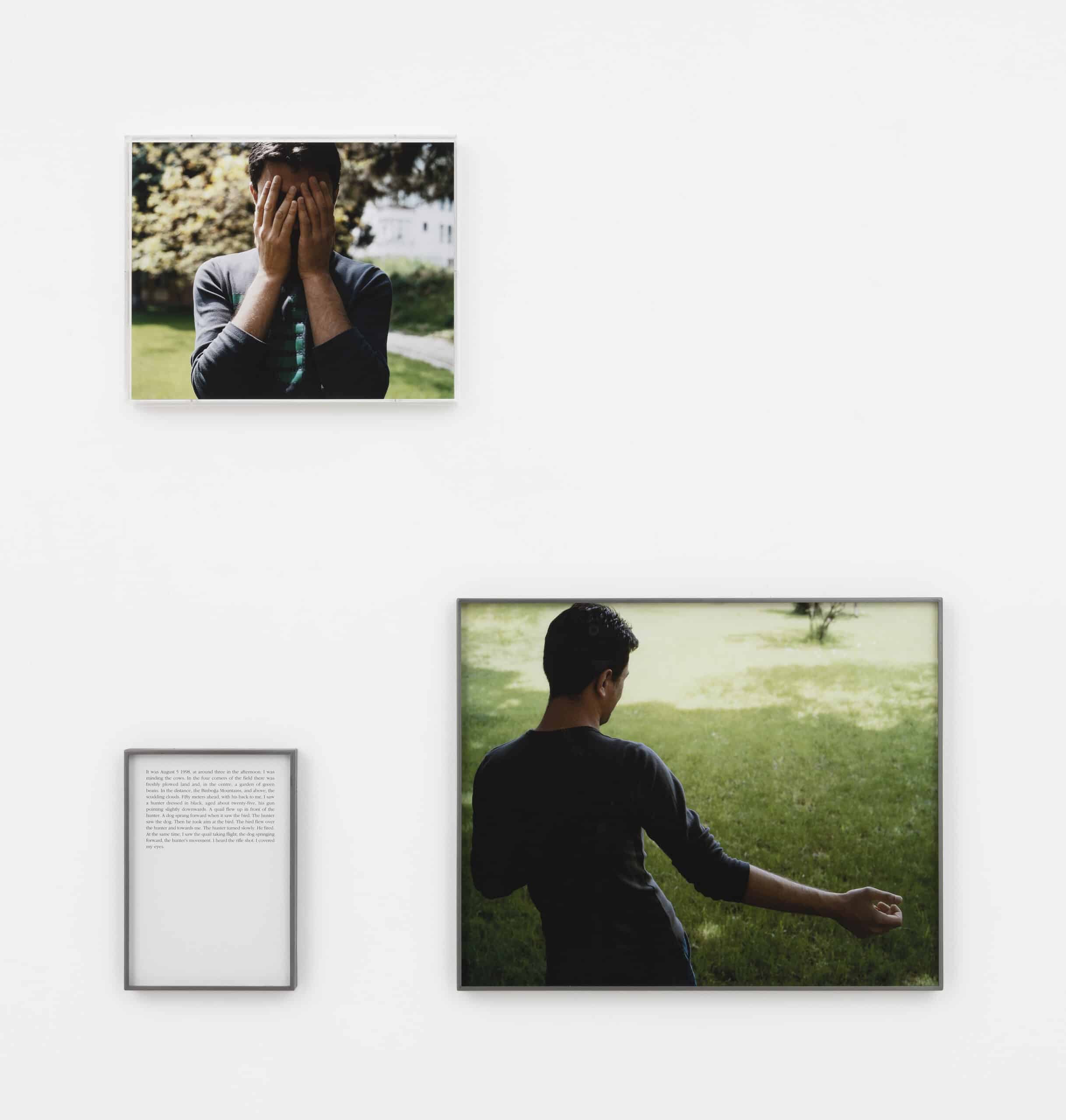

Aveugle au fusil [Blind with rifle], Colour photographs, Photocomposed texts © ADAGP, Paris 2023

Then I realized I was no longer alone. Someone on the other side of the room was speaking. Not in a whisper, nor in a particularly loud voice either, but distinctly, as one does when one wants to be heard. It was a Black man in a dark suit: one of the museum’s custodians. Facing each photograph, he would read the text. His movements were calm and collected, almost ritualistic; he would go from image to image, in order, honoring each installation, slowly voicing each description.

Art theory in its infinite wisdom might call that an activation, a reactivation, a reenactment. But this was so much better! It was unplanned, the custodian thought he was alone, at least at first, and he did not stop when we exchanged smiles. What he was doing was neither private nor public nor hidden nor enacted. It was a private moment experienced aloud within the space and delivered as it were to an invisible, friendly assembly.

This custodian was looking at and watching over more than the artwork itself: he was keeping secrets, treasures, the secret of these last images and perhaps much more (reminding me again of the exhibition by Mohamed El Khati and Valérie Mréjen devoted to that line of work, Gardien Party).

For everything was happening as if — by pronouncing others’ words, by giving voice to their speech, by adjusting his seeing eye to their blindness — that man was checking on his humanity while I was checking on mine. Perhaps this is exactly what speech allows us to do: to check on our humanity, to assess, experience and participate in it, starting over each time we take the floor.

Marielle Macé

Translated by Philippe Aronson

1 Judith Butler, When is Life Grievable? Verso 2009

2 Marielle Macé, Nos cabanes, Lagrasse, Verdier, 2019

3 Françoise Frontisi-Ducroux, Du masque au visage. Aspects de l’identité en Grèce ancienne, Paris, Flammarion, 1995

4 Michel de Certeau, « La prise de parole » (1968), in La Prise de parole, et autres écrits politiques, edited with an introduction by Luce Giard, Paris, Le Seuil, 1994

5 February 5-May 10, 2015, Musée d’art contemporain, Montréal, Canada.