Distraction: the term is polysemic. In taking as my starting point the five-way portrait of Marcel Duchamp made in 1917 in a Broadway studio using a hinged mirror, I could have explored the idea of inattention. That of a quick gaze, unaware of how the photo was taken, pinpointing differences and taking this image to show a simple meeting of friends in a smoking room. Or I might have followed the path of dispersal—that produced by the effect of the montage of reflections, which, this time highlighting repetition, unsettles the gaze. I opted instead to examine distraction as diversion—that offered by photography and its practice, which includes a rich tradition of playfulness.

It was important, for instance, to look to the diversity of carnival photography, which, alongside multiple portraits, also featured whimsical backdrops and photo stand-ins, funhouse mirror reflections, and a photo shooting range with the portrait taken upon hitting the mark. While the latter attraction seems to have been a photographic updating of an existing carnival technique, the other carnival images owed a great deal to amateur photography. In Avant l’avant-garde, du jeu en photographie (1890-1940) [Textuel, 2015], Clément Chéroux shows how, in the early 20th century, carnival photography, as well as the illustrated press, novelty postcards and film, borrowed from the playful repertory of “recreational photography”, encompassing the multiple portrait, among many other techniques using photogram, photomontage, superimposition, the quest for unusual angles, deformation and more.

“Recreational photography” emerged around 1890, when the automation and industrialization of photography, embodied by the Kodak slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest”, had allowed for the emergence of a new generation of practitioners for whom photographic operations could be reduced to shooting alone. They could indeed settle for picking up their prints and freshly loaded camera from the shop, without ever knowing what occurred inside the box. The “button pressers”, as these men—and increasingly, women and children—were readily called, challenged the established amateur photography, which was to the contrary rooted in technical mastery and knowledge of the process.

![<i>Les récréations photographiques</i> [cover page], 1891, by A. Bergeret and Félix Drouin, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1891.](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/001--scaled.jpg)

Albert Bergeret and Félix Drouin, « Reproductions directes ». Les Récréations photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1891, p. 9 (Boston Public Library)

Albert Bergeret and Félix Drouin, « Reproductions directes ». Les Récréations photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1891, p. 10 (Boston Public Library)

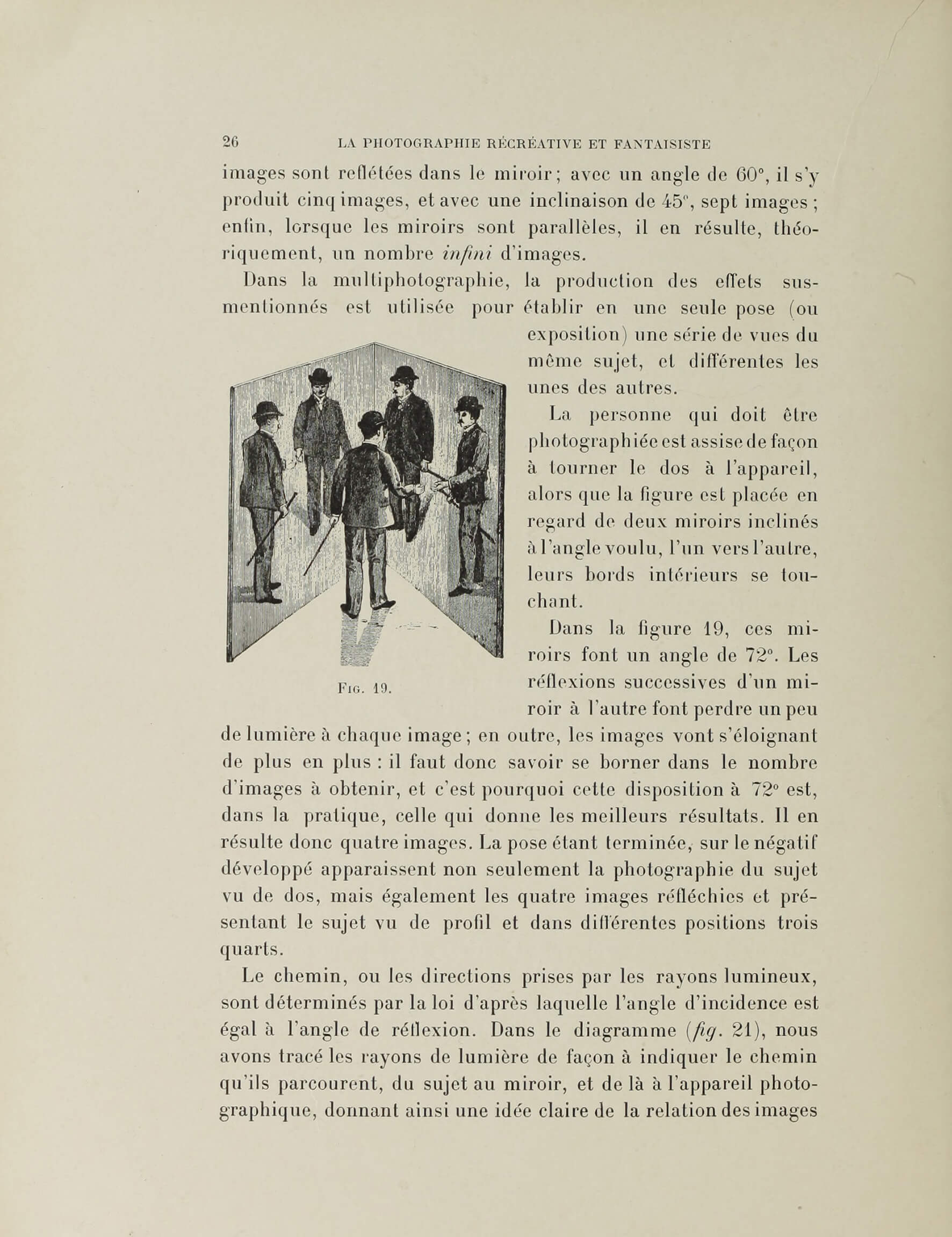

César Chaplot, « La multiphotographie », La Photographie récréative et fantaisiste – recueil de divertissements, trucs, passe-temps photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1900, p. 26 (Getty Research Institute)

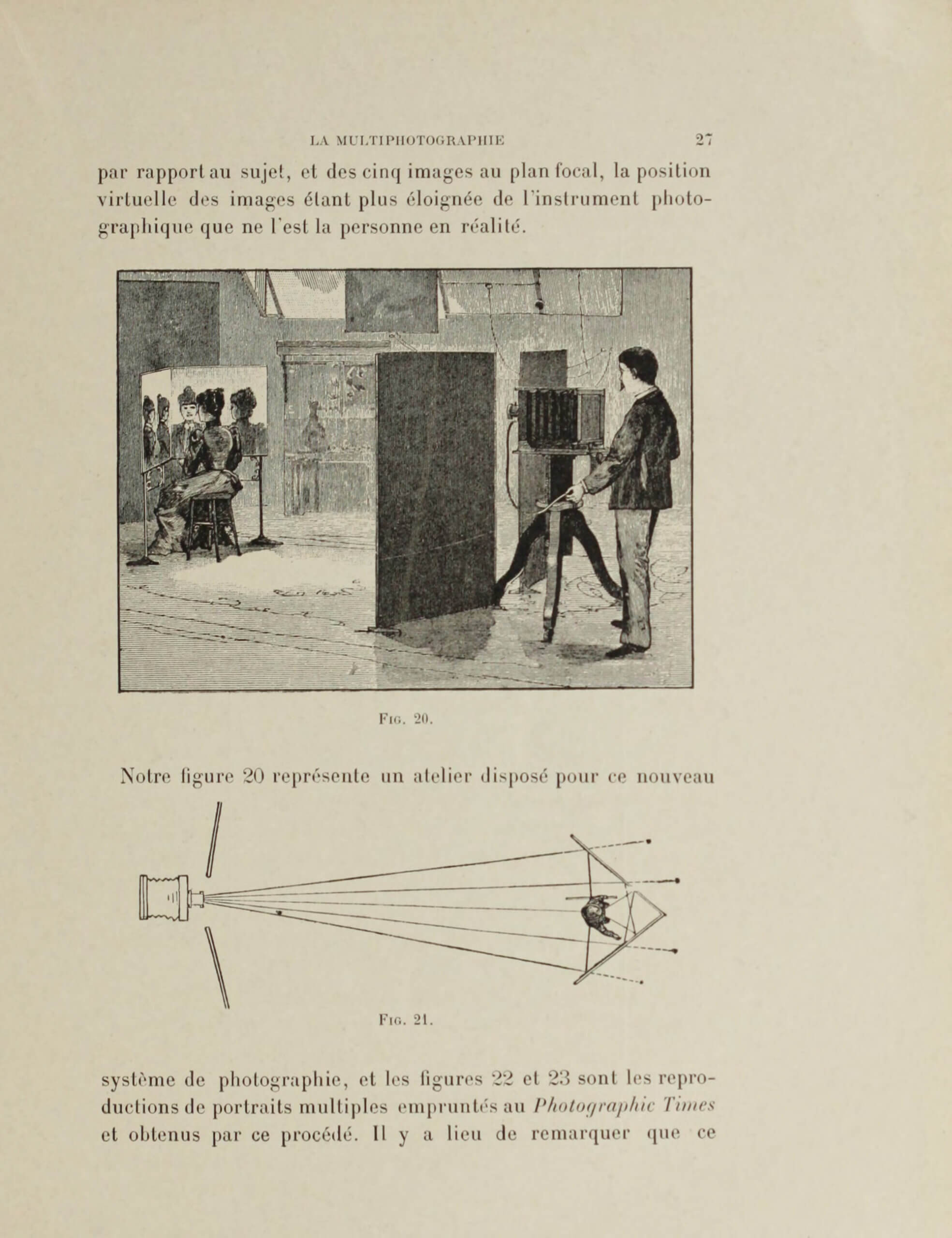

César Chaplot, « La multiphotographie », La Photographie récréative et fantaisiste – recueil de divertissements, trucs, passe-temps photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1900, p. 27 (Getty Research Institute)

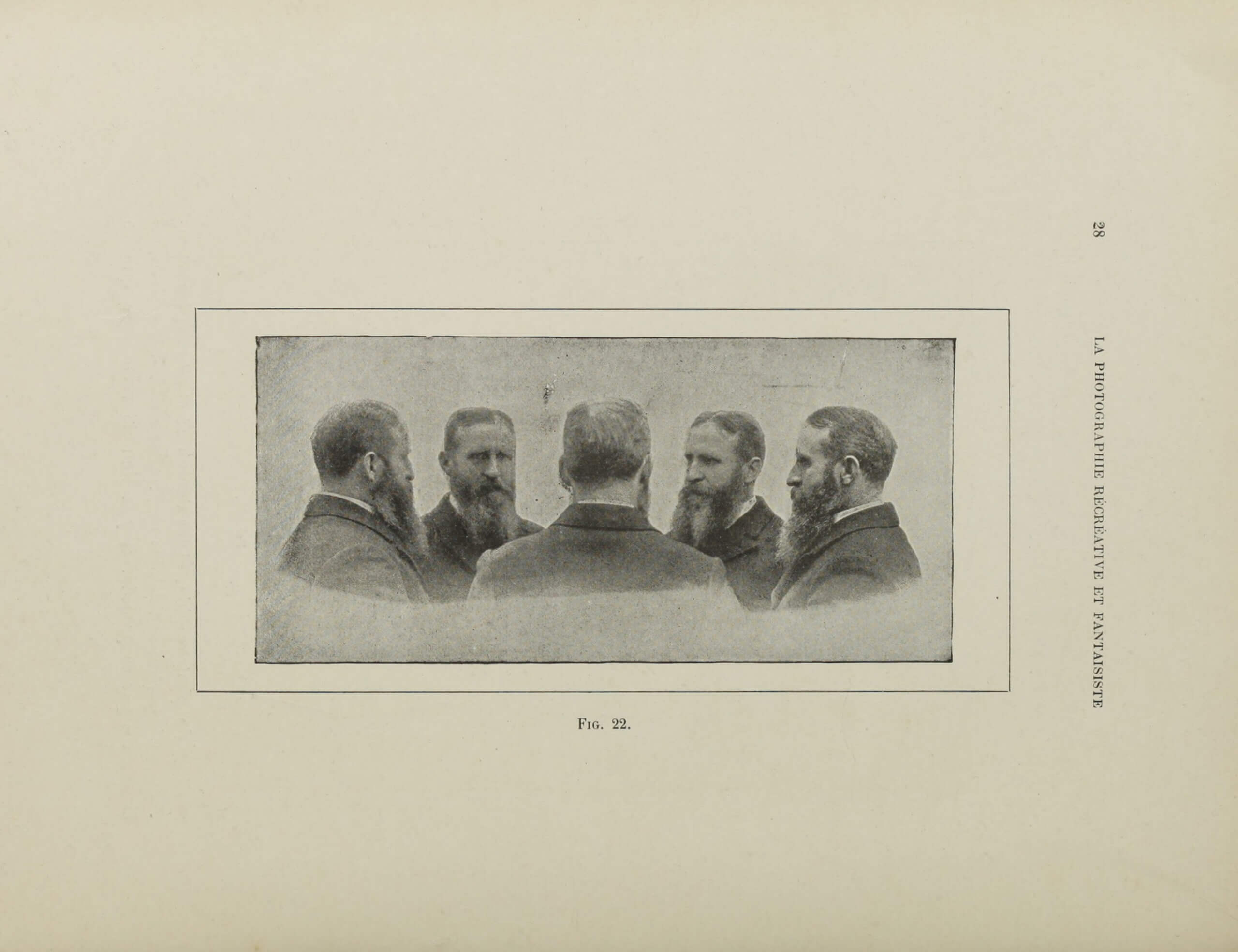

César Chaplot, « La multiphotographie », La Photographie récréative et fantaisiste – recueil de divertissements, trucs, passe-temps photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1900, p. 28 (Getty Research Institute)

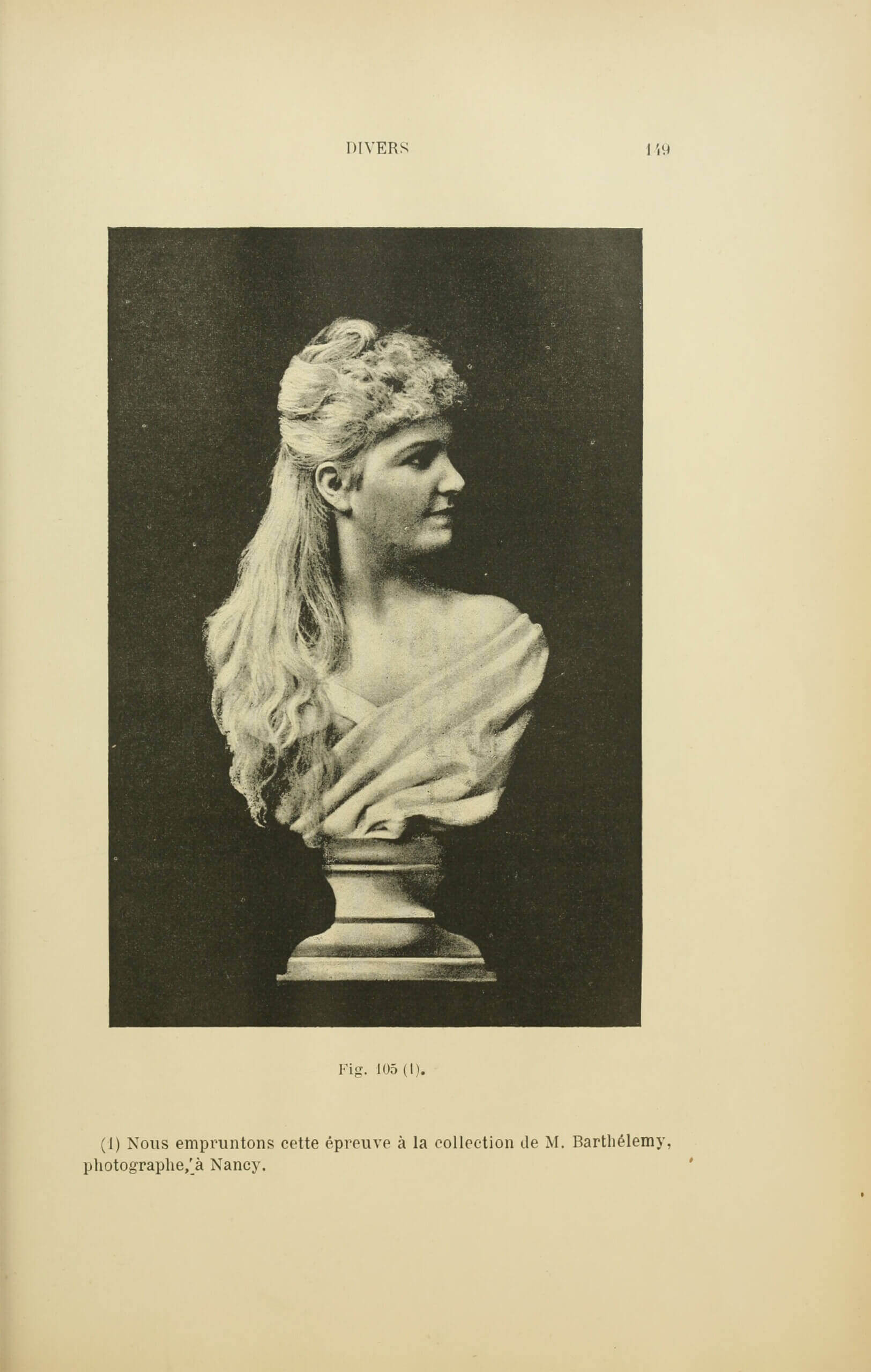

Albert Bergeret and Félix Drouin, « Reproductions directes ». Les Récréations photographiques, Paris, Charles Mendel, 1891, p. 148 (Boston Public Library)

Gabriel Mareschal, « Récréations photographiques. Photographies amusantes sur fond noir ». Revue La Nature, n° 1026, Paris, Masson, 1893, pp. 132-133

The democratic ideal of photography sought to emerge but led to poorer quality of use, which recreational photography, launched by experienced amateurs concerned with these evolutions, wished to correct by combining diversion and learning. While recreational photography aimed to bring together the practical and the pleasant, Chéroux distinguishes educational from attractive recreation. The former, with its instructive ambition, often took the form of challenges launched for new practitioners: photographing a quickly-moving subject or a subject at night, or both simultaneously, for lightning or fireworks, for instance; printing photos on original surfaces, to decorate a lampshade or a cushion, etc. The latter, strictly for amusement, seem to feature the human figure as a common denominator. This figure was multiplied, deformed, fragmented and combined. The caricatural photography (or photo-charge, in French) produced through photomontage is one such example.

As we might expect, attractive recreation met with the greatest success. Its principle of playfulness above all was heightened by carnival photography and the novelty postcard industry, whose history Carole Boulbès compellingly overviews in her recent publication De la carte à Dada, photomontages dans l’art postal international (1895-1925) [Éditions du Sandre, 2020]. And yet, why not try to revive the ambivalence at the root of recreational photography? Why not try to explore contemporary questions around photography and image today, while involving play? This is the idea that I’ve proposed to different artists, but with one constraint: if recreational photography was historically diffused in books and periodicals, what form might it take today? That of the tutorial, clearly.