EDITORIALS

Adieu au langage, Jean-Luc Godard, 70 minutes, 2014

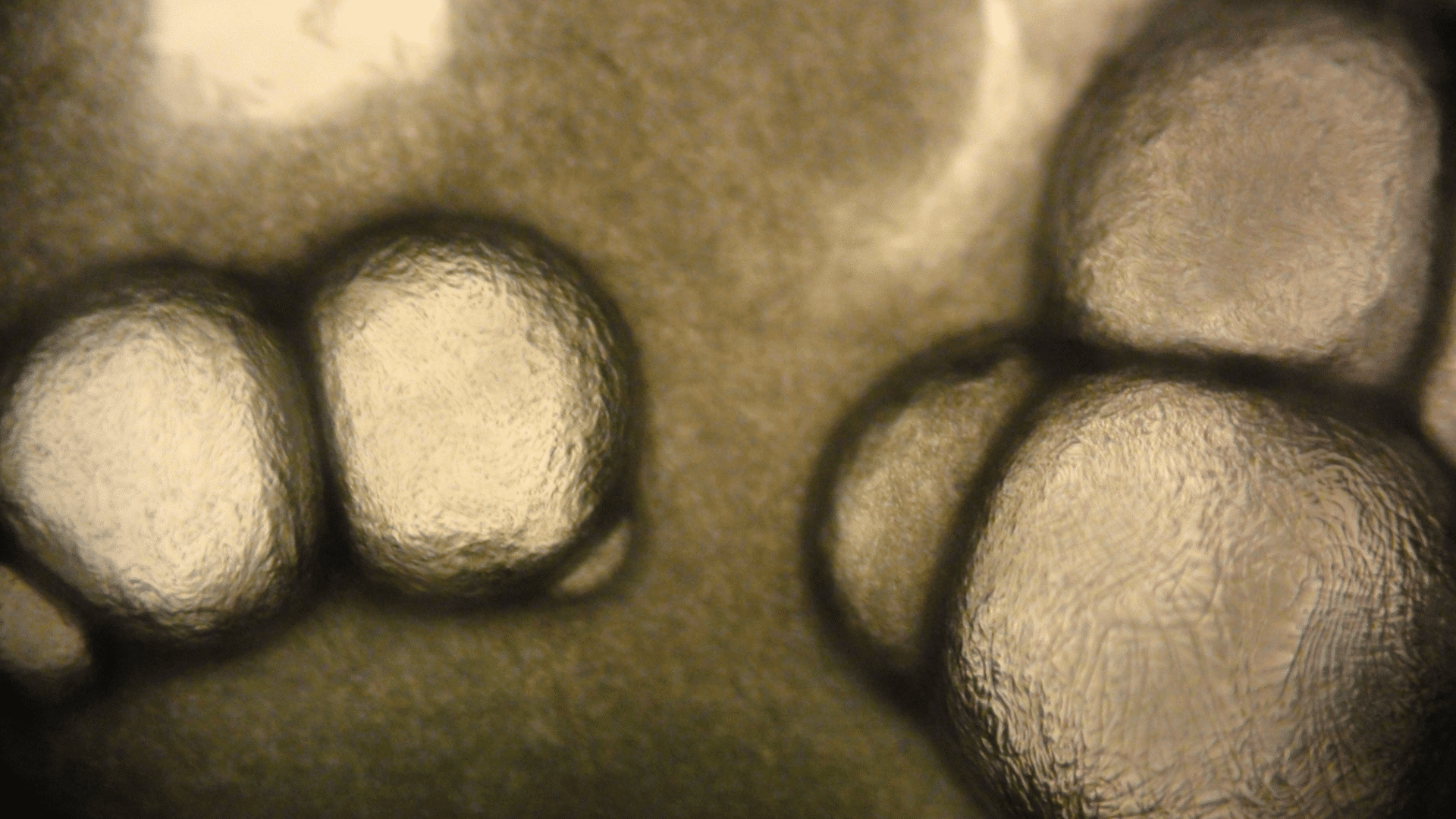

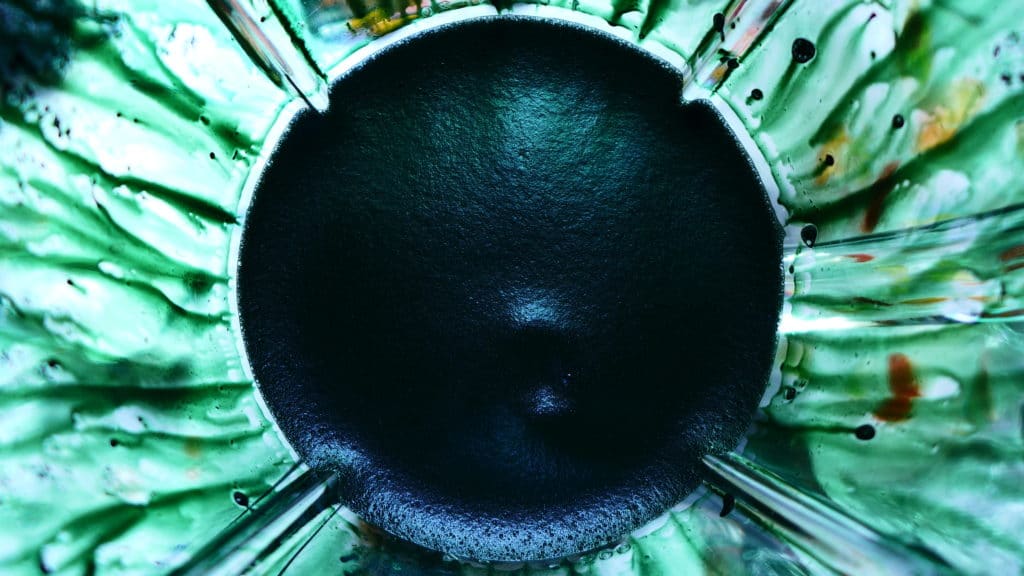

![Emilio Vavarella, <em>Animal Cinema</em> [film still], 2017. HD video, 00:12:12. Shot by a Grizzly (Ursus arctos ssp.) in Alaska (USA) and uploaded on youtube by Brad Josephs, May 17, 2013.](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Chiocchetti_Animal-Cinema-dEmilio-Vavarella-scaled.jpg)

Emilio Vavarella, Animal Cinema [film still], 2017. HD video, 00:12:12. Shot by a Grizzly (Ursus arctos ssp.) in Alaska (USA) and uploaded on youtube by Brad Josephs, May 17, 2013.

Which new visions of the living world have struck me?

In attempting to respond to this question, I found myself in the mouth of bear, an animal particularly dear to me for its dual features of strength and fragility. Put in these terms, it could be surmised that this was something real, that I had become a veterinary dentist. In fact, it was a work by Emilio Vavarella, Animal Cinema, that led me to spend hours contemplating an image of the inside of a brown bear’s throat, a shot involuntarily captured by the mechanical eye of the camera she had just swallowed. Animal Cinema is a highly fluid and psychedelic montage of found footage of animals interacting with cameras that have been misplaced or removed from their human owners – one of those creations unleashing a tide of post-anthropocentric interrogations. In his extremely enlightening text on the tick, Giorgio Agamben makes reference to Jakob Johann Freiherr von Uexküll, pursuing his vain and frustrating search for logical-temporal explanations of phenomena that we cannot comprehend, due to our inability to conceive of perceptions arising from the eyes and minds of non-humans. Frustration in fact reaches new heights concerning the tick, given this acarid’s lack of eyes. In his essay What Is It Like to Be a Bat? Thomas Nagel explains that it is impossible to respond to this question from the sensorial viewpoint of a bat, hindered from imagining this by our status as human beings. What conclusions might be drawn from all of this? That any speculation on the animal gaze and psyche is fanciful? That we are condemned to remain prisoners of anthropocentrism?

But let’s get back to the bear’s mouth. When I gaze at her image, her sharp canines immediately bring to mind a disturbing sculpture in the Jardin des Plantes, the Dénicheur d’oursons [the bear hunter] by Emmanuel Frémiet (1886). It shows a struggle to the death between a bear and a hunter who has killed her cub: despite the knife buried in her throat, the animal is on the verge of making one last effort and devouring the man. The work is so blatantly violent that I wonder what passers-by think when they see it – who they are rooting for. Now, everything plays out as though Google had also learned to read its users’ thoughts and unconscious associations of ideas: I enter the Latin name of the bear hero of Animal Cinema, Ursus arctos ssp., and the top results include a link from the International Association for Bear Research and Management to the Human-Bear Conflicts Workshop, a research workshop that has existed since 1987, with a forthcoming session in October 2022 near Lake Tahoe, Nevada. I confess that I’d really love to attend. How to escape anthropocentrism? In the contributions to this second issue of Palm, I’m going to explore this along with you, in the company of the artists, writers, philosophers and thinkers who have attempted to answer this question.

Federica Chiocchetti / Photocaptionist

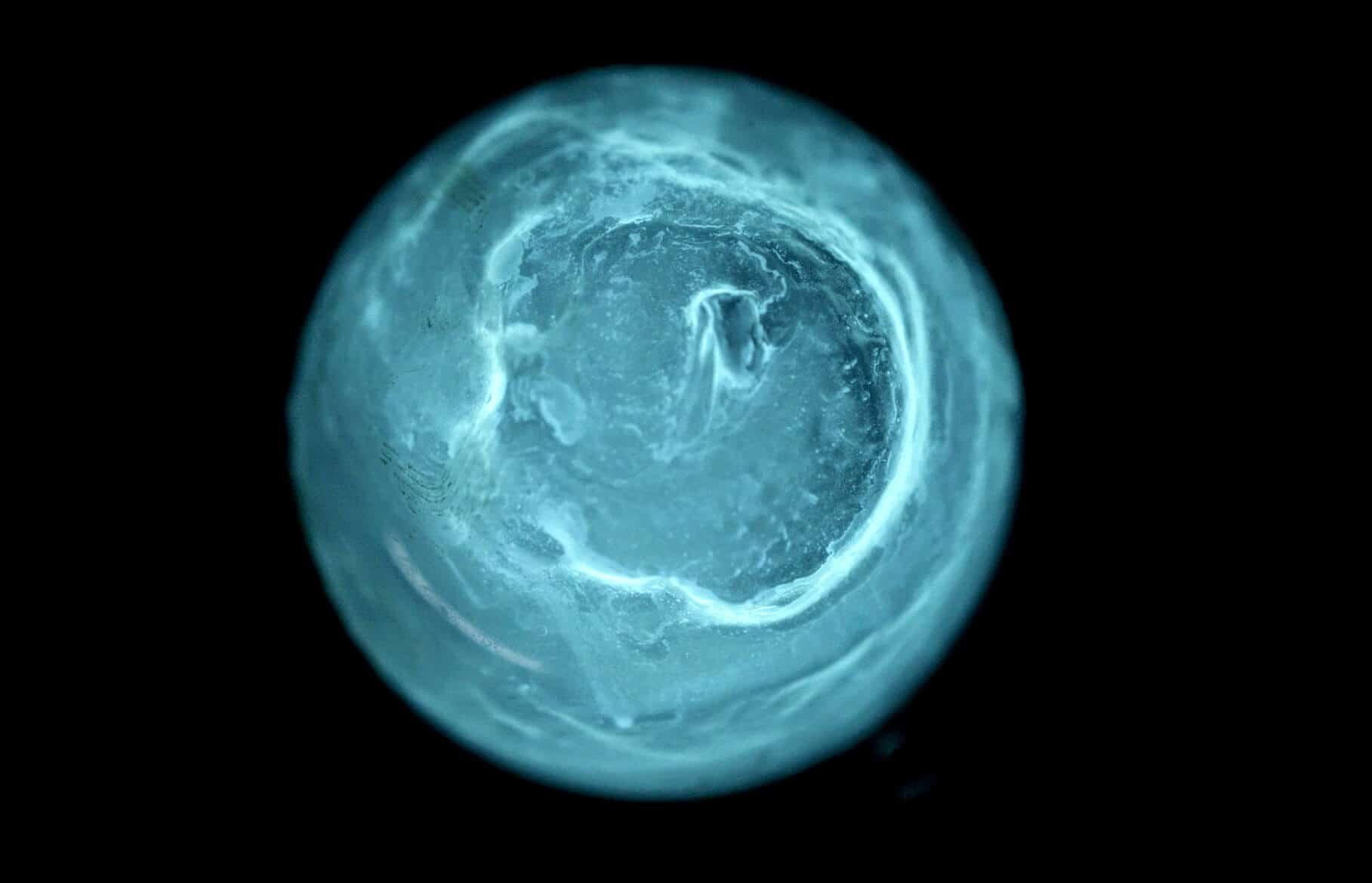

Jean Painlevé, photogramme extrait du film L'hippocampe,1934, 13'45'', noir et blanc. Réalisation : Jean Painlevé. Copyright Les Documents Cinématographiques, Paris.

Jean Painlevé, The Sea Horse, 1934

This eye, filmed by Jean Painlevé and his camera operator, André Raymond, is that of a sea horse. It appears in a 1933 short film, one of many documentaries that Painlevé, a biologist by training and a free-thinking friend of the surrealists, devoted to aquatic animals. In a tribute, Jean Rouch spoke of this filmmaker, who died in 1989, as the “pioneer of the cinema of tomorrow”. One thing is certain: when he made his first films in the mid-1920s, Painlevé was following a well-established tradition of scientific films using the art of cinema – magnification all the way to microcinematography, acceleration or slow-motion – to show new images of living worlds. But is it Painlevé’s poetry, his humor or his desire to speak to the broadest possible audience that led him, in his comments, to multiply the references to humans? The sea horse has “a dismayed air transformed into worry by the movement of her eyes”. What film might Painlevé have made today, now that the anthropocentric paradigm has been broadly called into question? Would he have settled for showing the sea horse’s eye as it had never before been seen? He undoubtedly would have sought to elucidate his vision.

Étienne Hatt

Sarah-Friend-lifeforms-screenshot-2

Anthropocentrism is an illusion. A simple viewpoint. A psychological crutch built some twenty-six centuries ago by the pre-Socratic thinkers Protagoras and Democritus, and still widely used today. The crutch is indeed a non-negligible comfort and allows in particular a whole section of continental as much as analytical philosophy to discard the knowledge of the real-in-itself. What indeed is the existent and is it possible outside the subjectivity of the mind that conceives it? Outside of any use, of any network of meaning? The task is certainly perilous.

It is, however, entirely possible to reverse this position: why consider consciousness and what is external to it on different ontological planes? A differentiation that often goes hand in hand with others, between animate and inanimate objects, material and immaterial, human and animal, and so much more. Uncorrelating the existent from human subjectivity is thus, for the philosopher Tristan Garcia, a way of “exorcising the fate of an original rupture in being” (T. Garcia, “Crossing Ways of Thinking: On Graham Harman’s System and My Own”, translated by Mark Allan Ohm, Parrhesia 16, 2013).

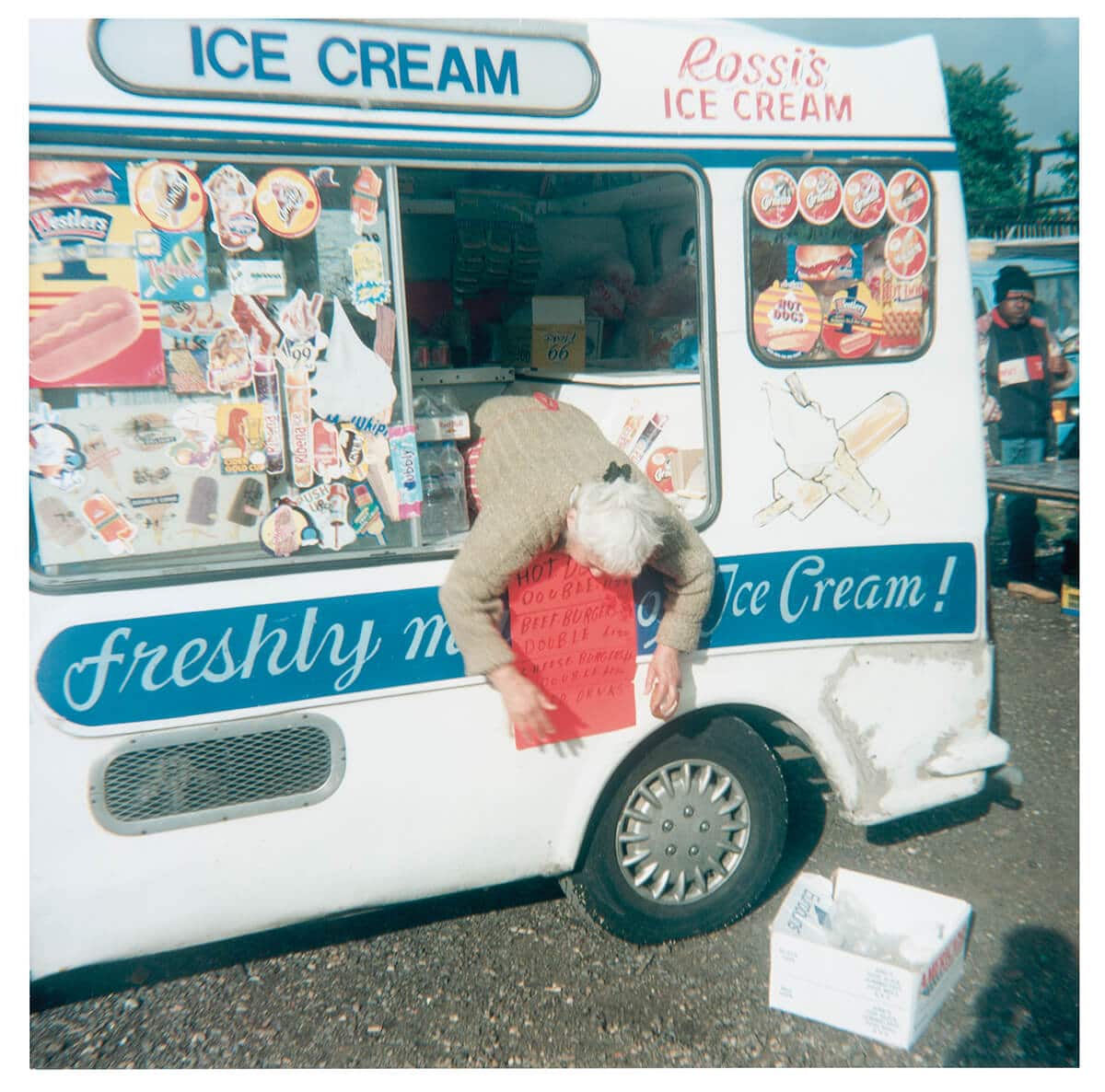

This anthrodecentrism not only makes it possible to consider the existent for itself, but also to extend the limits commonly understood as being those of consciousness, thus operating a return to many traditional conceptions of being. Hyacinthe, a new project by artist and director Matthew Lessner that he will talk us through, combines documentary, animated film, breathwork, altered states of consciousness and neurofeedback, with the aim of reflecting the electrical activity of the brain of the viewer in the very film that they are watching. Inanimate objects, do you have a soul? The Lifeforms brought into the world by Sarah Friend, perishable NFTs if we do not take care to share them, will come to revive this question.

Aude Launay

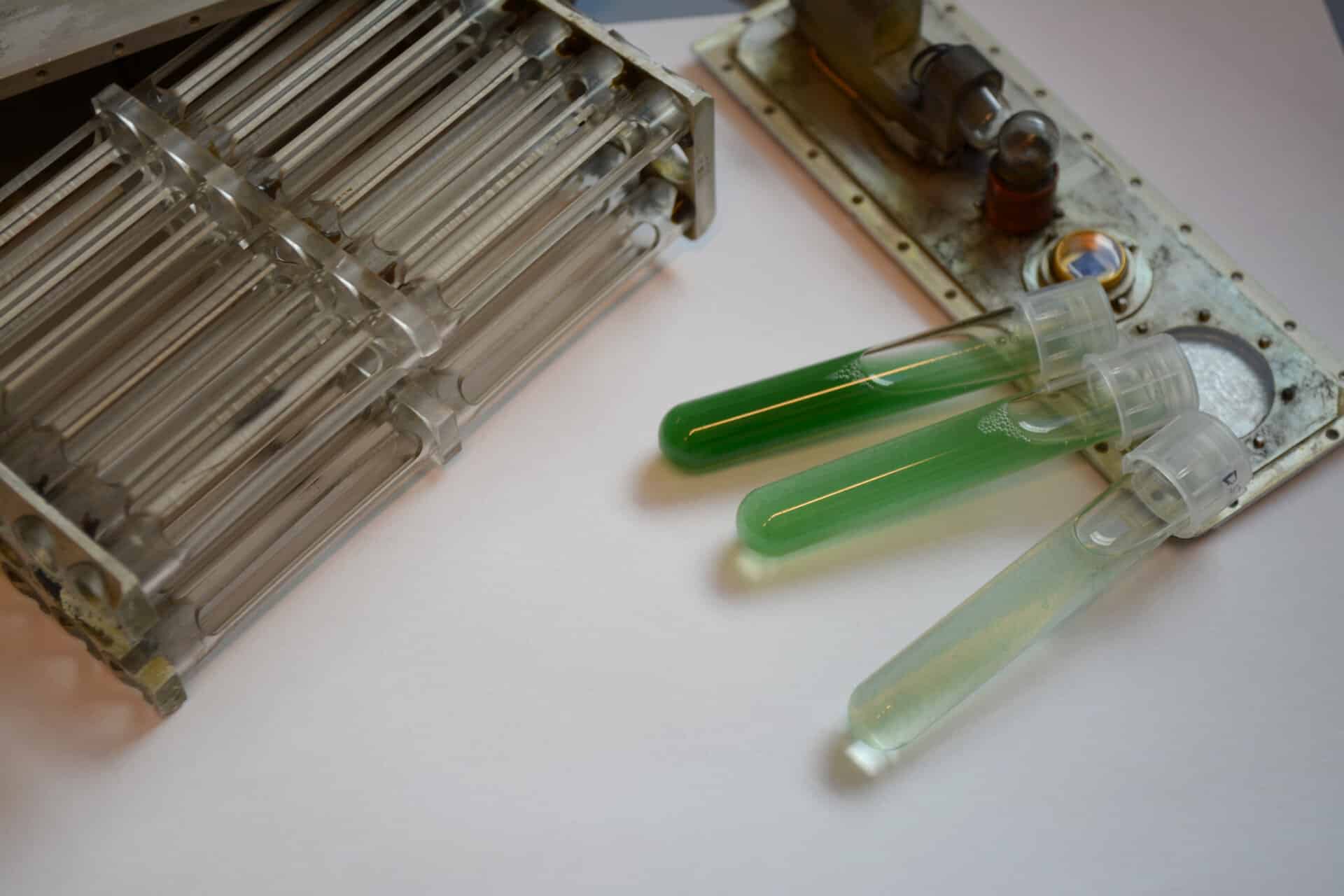

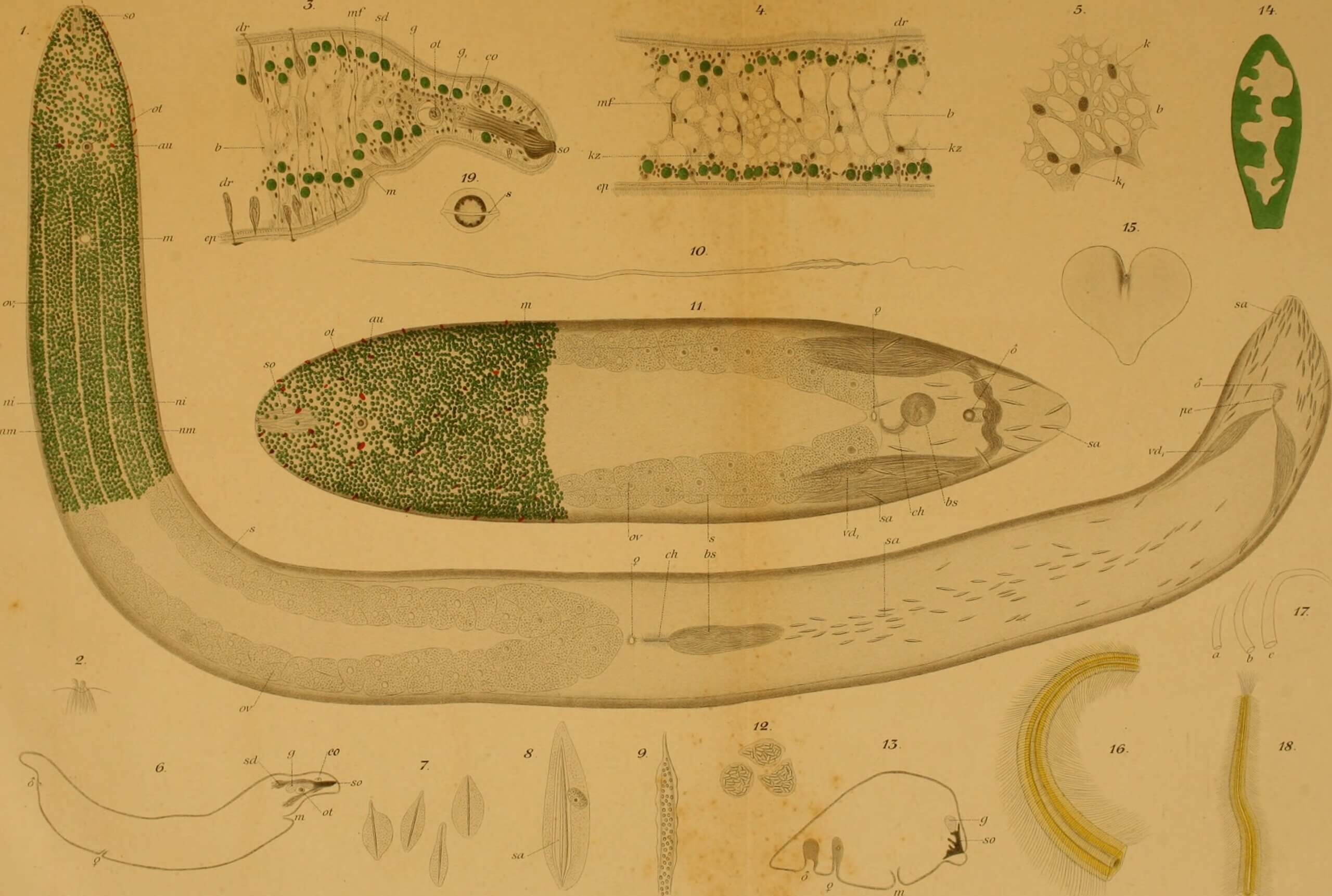

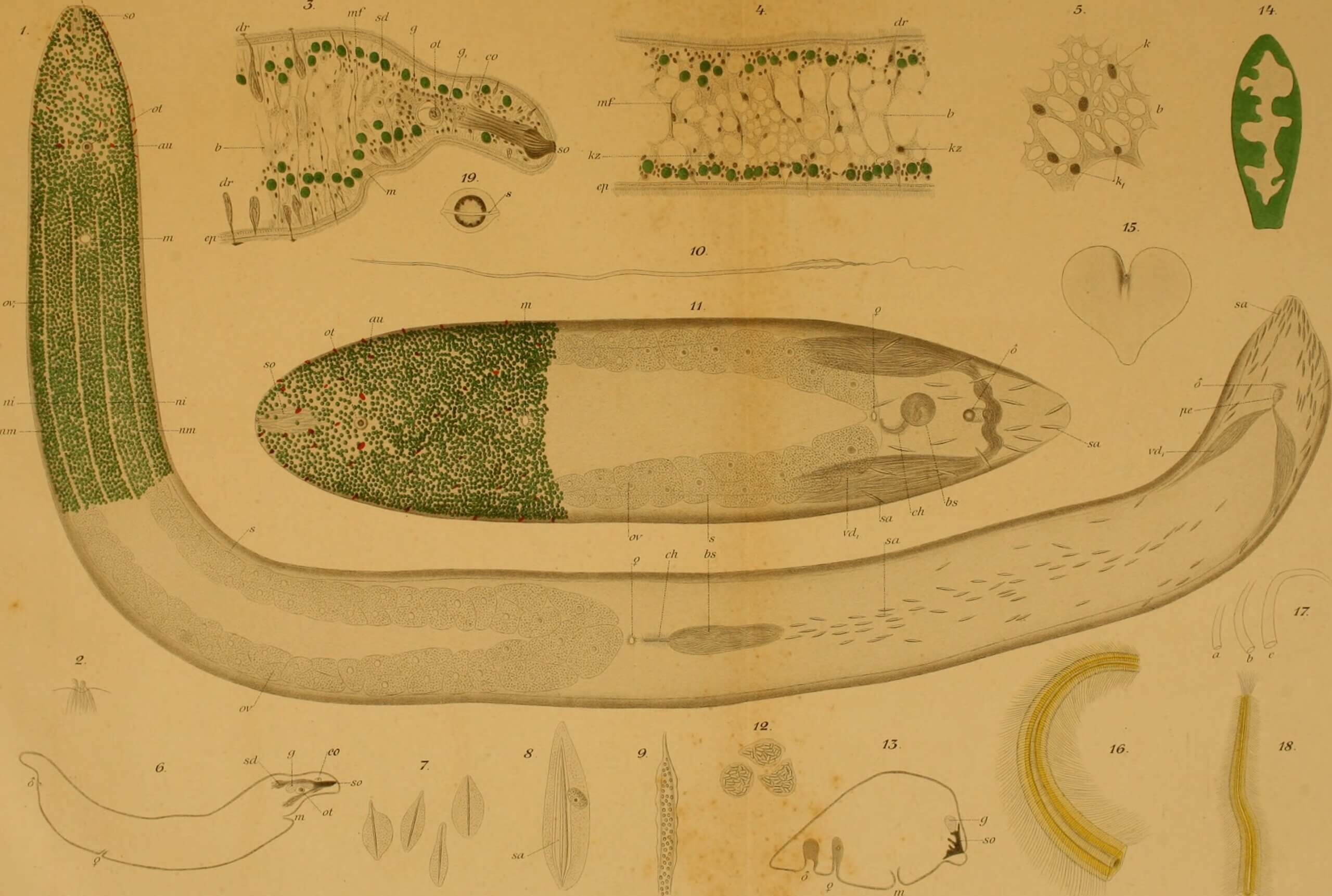

Ludwig von Graff (1851-1924) and Gottlieb b. Haberlandt (1854-1945), The organization of the Turbellaria Acoela. With an appendix on the structure and importance of the chlorophyll cells of Convoluta roscoffensis.

The Symsagittifera Roscoffensis species is a symbiotic sea worm found on the beaches of the Atlantic coast. It is an animal that ingests, but does not digest, its micro-algae partner hosted under its epidermis, getting nutriments from the latter’s photosynthetic activity. This species is an iconic example of symbiosis that the biologist Lynn Margulis (1938-2011), celebrated for her endosymbiotic theory of evolution, was fond of citing. Margulis considered that Darwinian theory, focused on competition, was incomplete, and affirmed that to the contrary, evolution was oriented by phenomena of cooperation, interaction and mutual dependence among living organisms. She opposed Neo-Darwinism’s “survival of the fittest”, and was in this sense an atypical figure in the scientific community. For Margulis, symbiosis was not an exception in the living world, but the general rule, proposing that evolution mainly occurred through leaps induced by symbioses merging organisms into new forms, called holobionts. She was indignant at how the notion of symbiosis was defined as a “mutually beneficial” association, as for her, this terminology was an application of economic vocabulary to the realm of the living; she preferred defining it as an association with reciprocal and shared advantages and/or inconveniences, a functional imbalance of the type 1+1+n…=1, “queering” rigid historical classifications of the living world. If biological wisdom can spark social transformations, it is imaginable that the dissemination of the symbiotic vision proposed by Margulis can allow us to escape a competitive view of the living world, and an exceptionalist view of humans, leading us toward an auspicious horizon of interspecies cooperation and nondeterministic fluidity.

Ewen Chardronnet

![Emilio Vavarella, <em>Animal Cinema</em> [film still], 2017. HD video, 00:12:12. Shot by a Grizzly (Ursus arctos ssp.) in Alaska (USA) and uploaded on youtube by Brad Josephs, May 17, 2013.](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Chiocchetti_Animal-Cinema-dEmilio-Vavarella-scaled.jpg)

Photographing plants and flowers is not particularly difficult, but in a sense, it is not particularly satisfying either, because the images lack movement, the element of the event, the representation of which is precisely one of the most important tasks proper to photography.