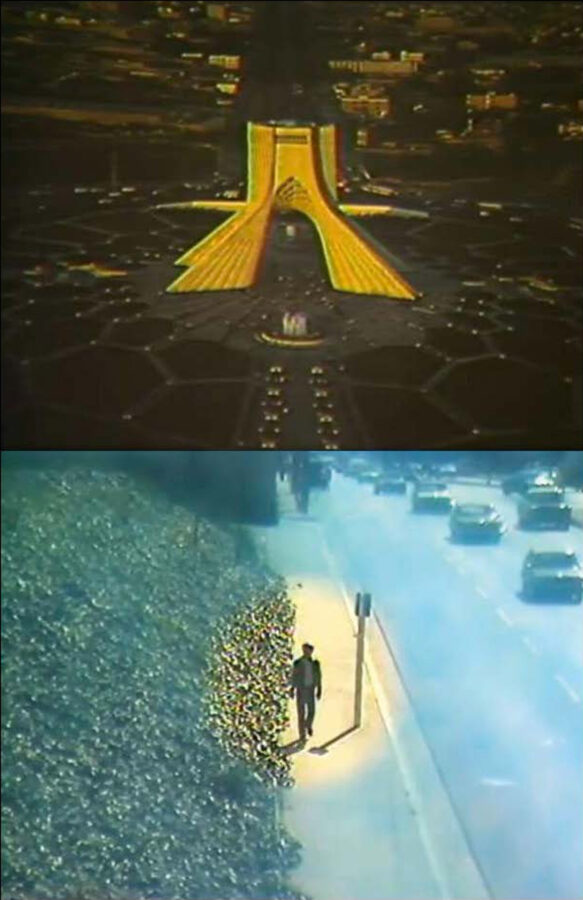

What remains of our identities abroad? Many memories and a few outward signs. After going undercover in Tehran (Haut Bas Fragile, 2017) and re-examining the story of the 1979 revolution via propaganda books (Rue Enghelab, 2019), Hannah Darabi investigates the traces of the Iranian diaspora in Los Angeles. She focuses on a reliable indicator: pop music cassettes.

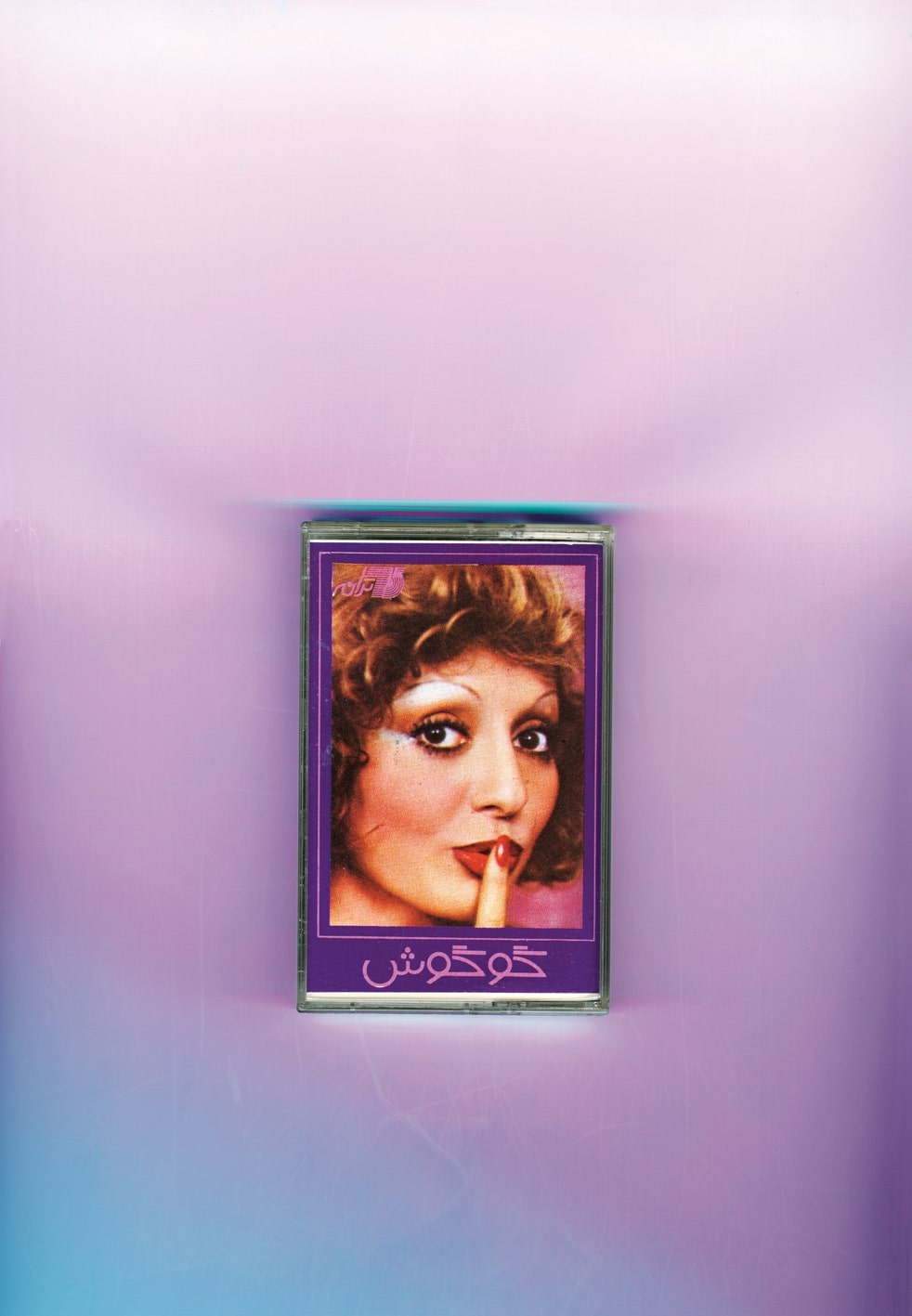

Holding her index finger to her lips, Googoosh asks for silence. Could the diva assoluta of Iranian commercial music, all fake eyelashes and wave set hair, be about to tell us a nasty secret? At least, that is what is suggested by the ambiguous close-up selected by the Taraneh Enterprises label for the cover of Nafas (Breath), a laidback duet released in 1984, five years after the fall of the Shah instigated by Ayatollah Khomeini.

Hannah Darabi, born in Tehran in 1981, has a whole collection of such cassette tapes. Approximately 150, found on eBay or at Music Box, the former cult record shop in Tehrangeles, the nickname given to the City of Angels and the primary adopted home of the Iranian diaspora, centred around this “Persian Square”, at the junction of Wilkins Avenue and Westwood Boulevard.

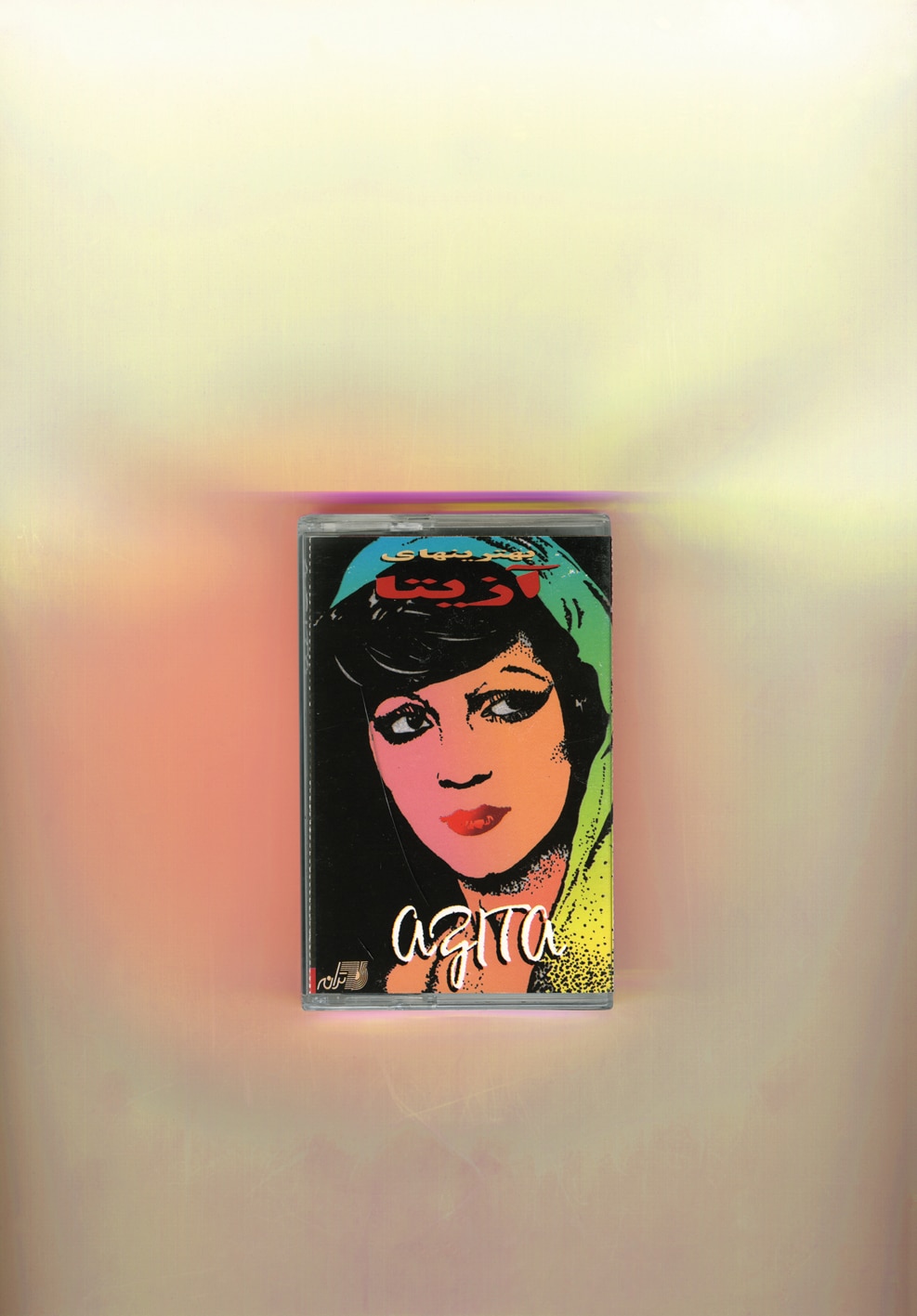

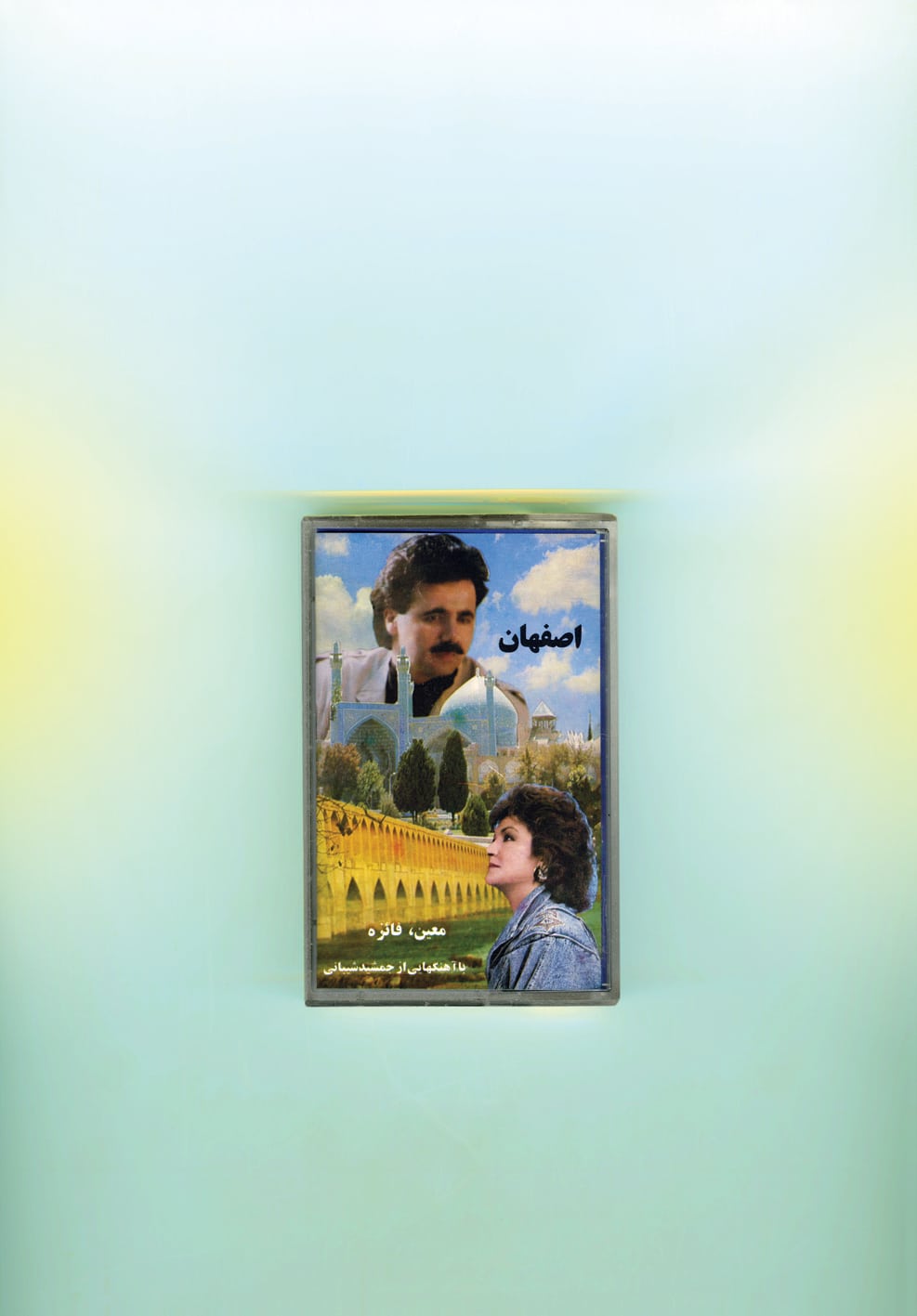

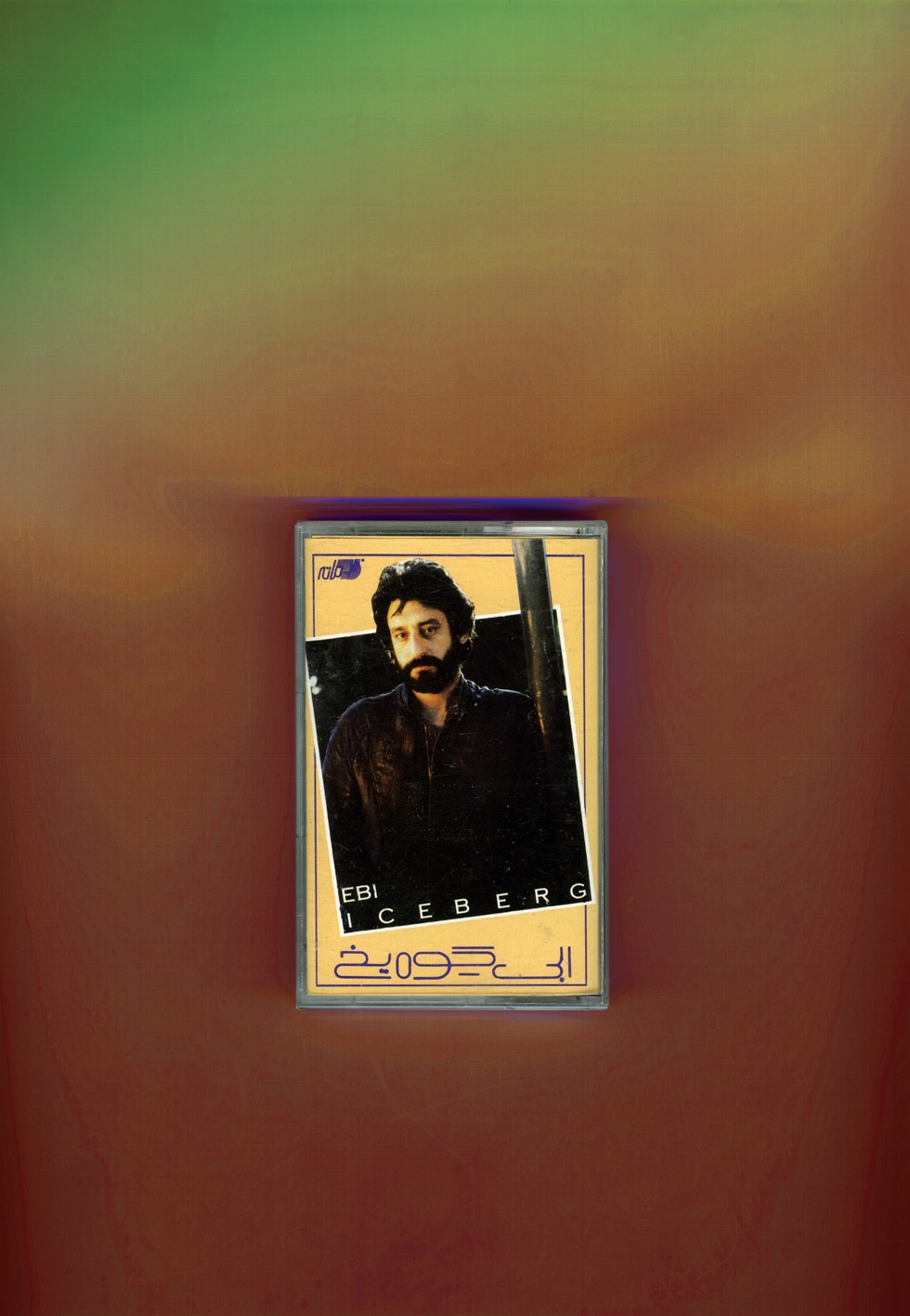

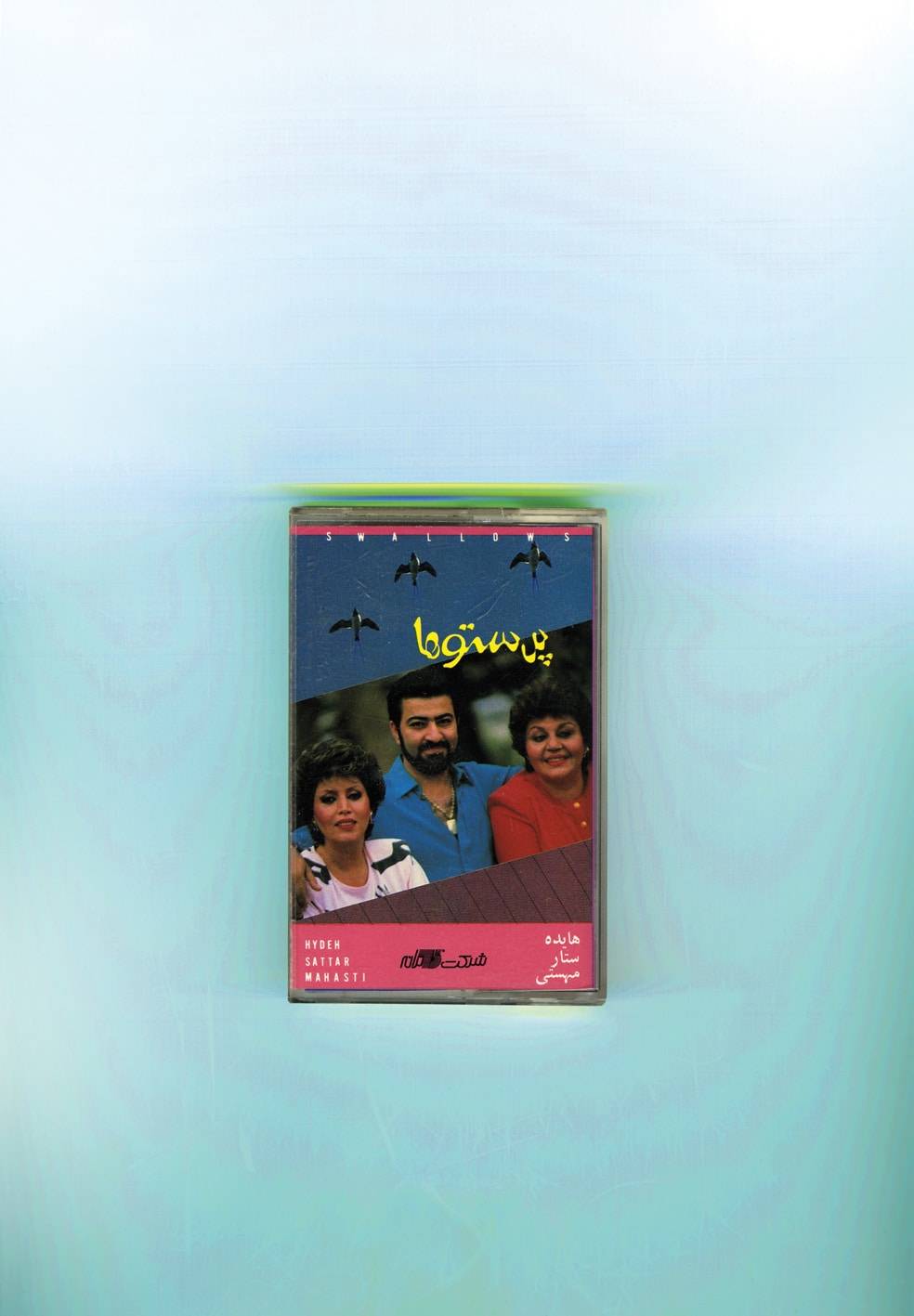

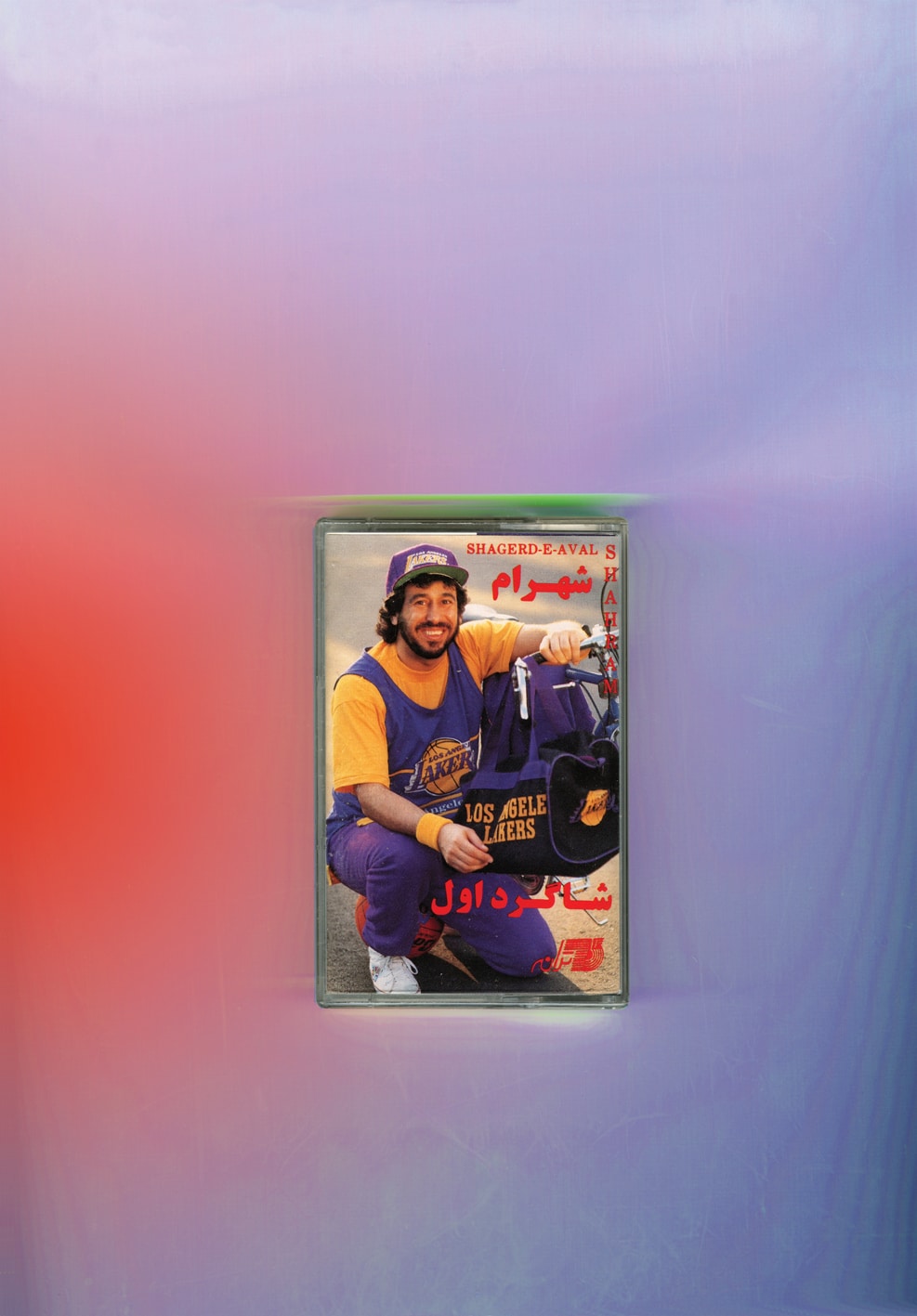

The artist scanned them one by one before adding faded backgrounds with hues ranging from mauve to grenadine, pistachio to indigo. Retro shades that give her inventory the dated charm of teen posters. Under the machine’s rays, the plastic case has formed a halo, accidentally elevating the object to iconic status. Which is somewhat ironic when you consider that these headline acts with a westernised look had to flee their country, pronounced enemies of the Islamic Republic, guilty of perverting the crowds with their so-called deviant tunes.

Dariush, Hayedeh, Shahram Shabpareh, Ebi, Jalal Hemmati… Exiled in California, these local stars who are now rendered anonymous initially sing of the wild hope of an impossible return before sticking to chaste ballads. Behind their modesty hide in equal measure the fear of censorship and a desire to please. Because their audience is far away from here, and when war and sharia law are breaking hearts over there, music is listened to in the same way that a balm is applied.

It has to be acknowledged, that due to a lack of funds, the quality is lower: empty lyrics, lurid rhythms and thrown together videos end up scrambling the sources of influence, and the codes of belonging. Nevertheless, the Losāngelesi unites a displaced people who are provided, through a few notes, with a means of transport and the gift of ubiquity. So much so that the ethnomusicologist, Farzaneh Hemmasi, compares this “low art” snubbed by the elites with the concept of “cultural intimacy” developed by anthropologist, Michael Herzfeld[1]. In other words, what is considered an embarrassment in public, yet provides, deep down, “an assurance of common sociality”.

Hannah Darabi is well aware of this paradox, as she herself has a complex relationship with this lousy music genre, that is illicit and effectively “stateless”. For a long time, her shyness kept her at a distance from the hits calibrated for partying, designating pleasure and bringing bodies closer together. Recently, she had a change of heart, and these by-products of pop music, an integral part of her culture, piqued her curiosity. But where the general interest is limited to the sophisticated formats pressed in Iran before the death throes of the Pahlavi dynasty, her own, very specific interest is focused on the declassified ones, those stamped “made in USA” during the 1980s and 1990s. Her online purchases reveal the back of the cards, indicating the movement of goods indexed to migratory flows. Above all, each find serves to fill a gap: the pale pirate copies distributed illicitly before MP3s rendered cassette tapes obsolete, are finally regaining back their original, gaudy, typical colours.

Indifferent to the “inherited nostalgia”, this patrimonialisation of melancholy theorised by Neda Maghbouleh, and a veritable cash cow for Tehrangeles, Hannah Darabi looks at these magnetic tapes with the same candid gaze as with the Orange County streets chock full of signs in Farsi, or the phone directory pages advertising the services of shrinks, lawyers or plastic surgeons from the Persian community. As if, in order to hear the echo it is necessary to evaluate the whole, and put the pieces back together. An identity jigsaw, Soleil of Persian Square creates a breach: as the investigation progresses, reality wavers.

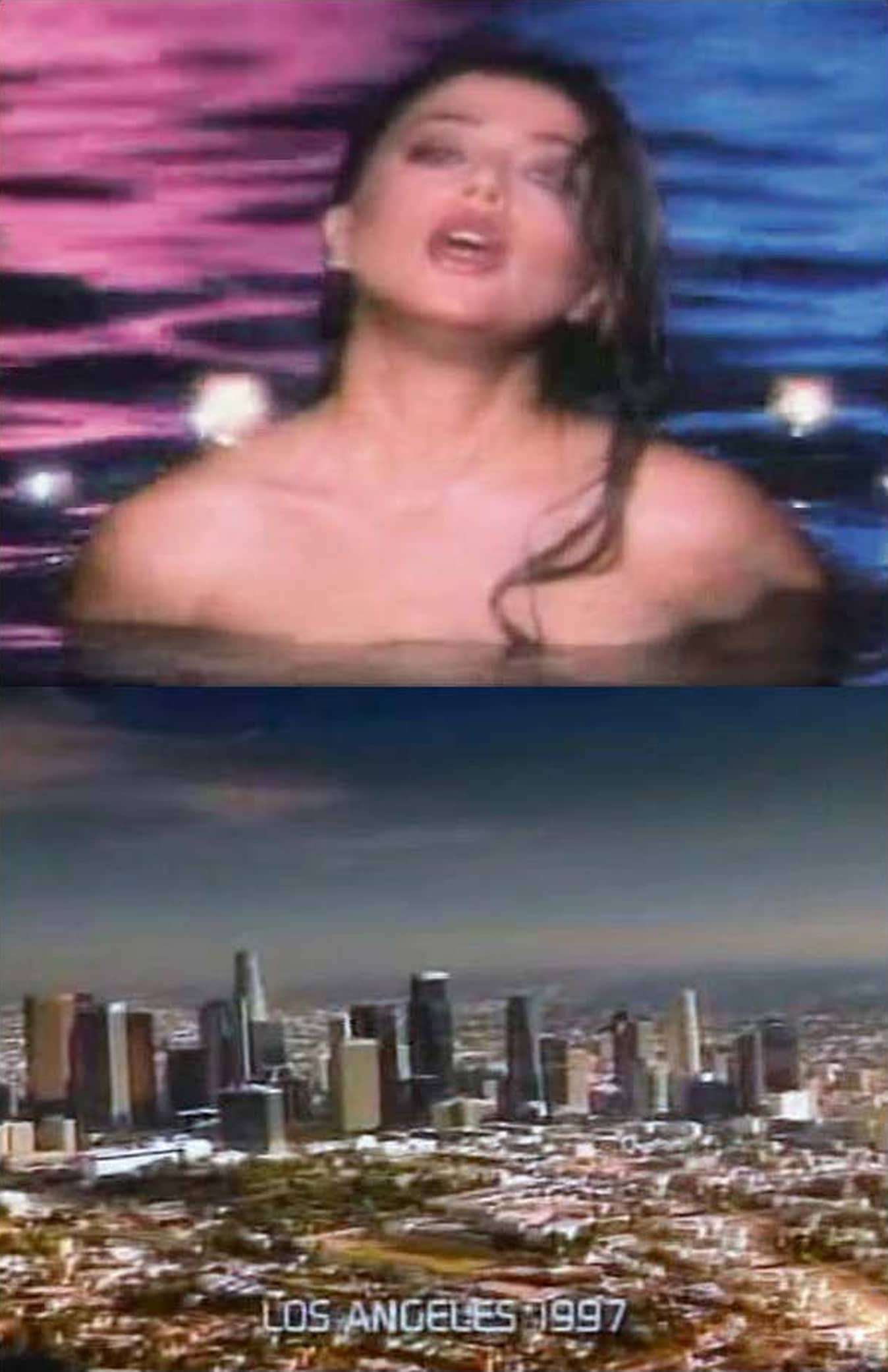

It is fact: music plays tricks, amplifying passions to the point of delirium. A side effect caused by the cassette tape, that is reproducible and cheap, and even more so by the music video, which is the embodiment of fiction. Hannah Darabi compiles several of them in slow motion, over a gloomy remix of Post California. When Susan Roshan’s shadow hovers over the city like a sensual spectre dominating the skyline, one thing is clear: pop music is an anthem.

Virginie Huet

Translated by Jacqui Chappell

1 Entretien fleuve accordé à Hannah Darabi au sein de l’ouvrage Soleil of Persian Square paru chez Gwinzegal.