How to photograph our ghosts, our fantasies? And how to photograph what is bygone but remains fixed in the present? These questions, which lurk behind Ishion Hutchinson’s poem Liechtenstein, run through Sammy Baloji’s entire oeuvre. To tell an interwoven story, a visit to an admired Kongo, or a dominated Congo, which is now both coveted and abandoned, Sammy Baloji first wanted to query the major narratives that smother the texture of real experience. By inverting the timeline, this photographer and videomaker has thus elaborated a series of strategies which give his singular aesthetic the plural quality of a weaving.

Courtesy of the artist © Sammy Baloji

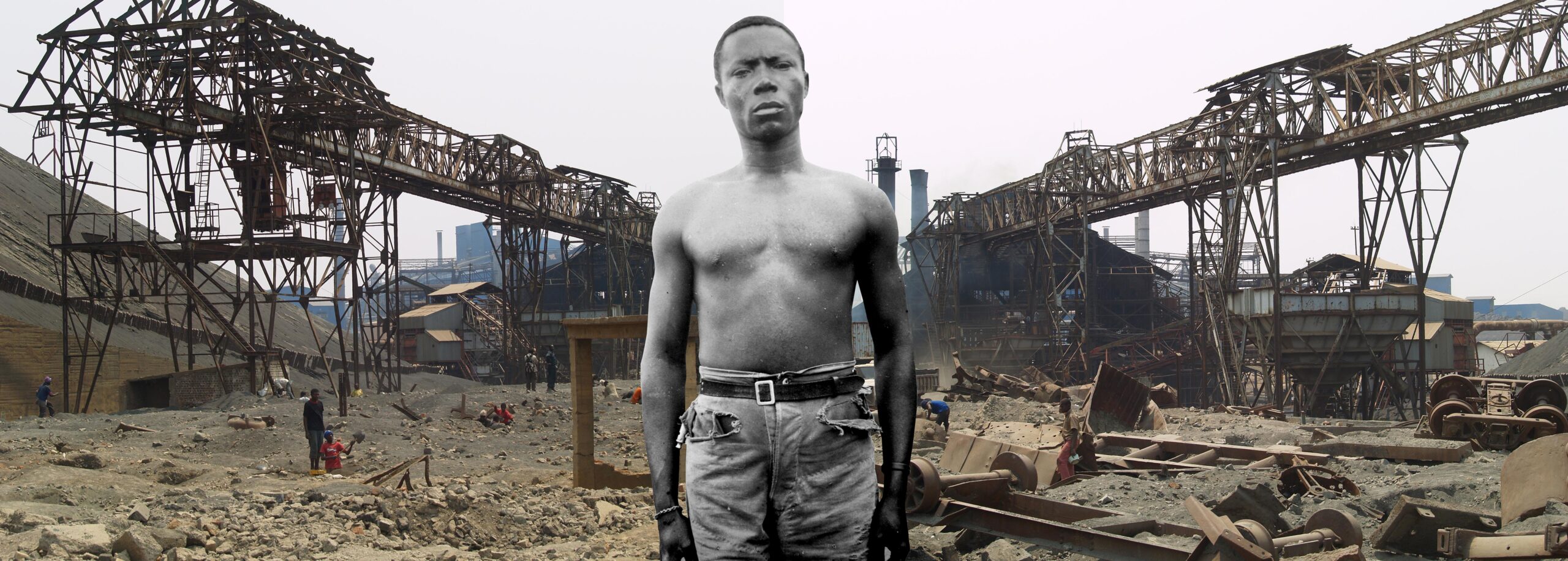

His initial strategy allowed him to spotlight the moribund landscapes of post-industrial Katanga. This region of Congo, rich in copper, cobalt, uranium and water, exploited as of 1906 by the Belgian ‘Union Minière Company’ of Haut-Katanga, which owed its monopoly to Léopold II, was then ransacked by Mobutu’s government, which placed the mines under the control of ‘Gécamines’, a state company that created jobs but soon went bankrupt. The series The Beautiful Time/La belle époque, presented by Sammy Baloji at the Museum for African Art in New York in 2012, drew up an audit of this ambiguous tale: “…though exploited”, Bogumil Jewsiewicki noted, “the workers were proud of the modern urban company they had built up” (Jewsiewicki, 2010). Sammy Baloji thus opposed his portraits of sites, now under the sign of ruins and rust, to the myths of a richly green equatorial forest, or a tabula rasa offered to a conqueror’s audacious knowhow, or even Indépendance Cha Cha. Romanticism is completely excluded from these photos because quite literally no one appears in them to convey an emotion shared by a soul and a site.

This exploration of what is quite clearly a man-made void has led to Sammy Baloji being called the “photographer of absence”(Jewsiewicki, 2011). He posed quite bluntly the question of the fate of the disappeared — today notoriously replaced by fleeting diggers and unemployed geological engineers (Niarchos, 2021).

Courtesy of the artist © Sammy Baloji

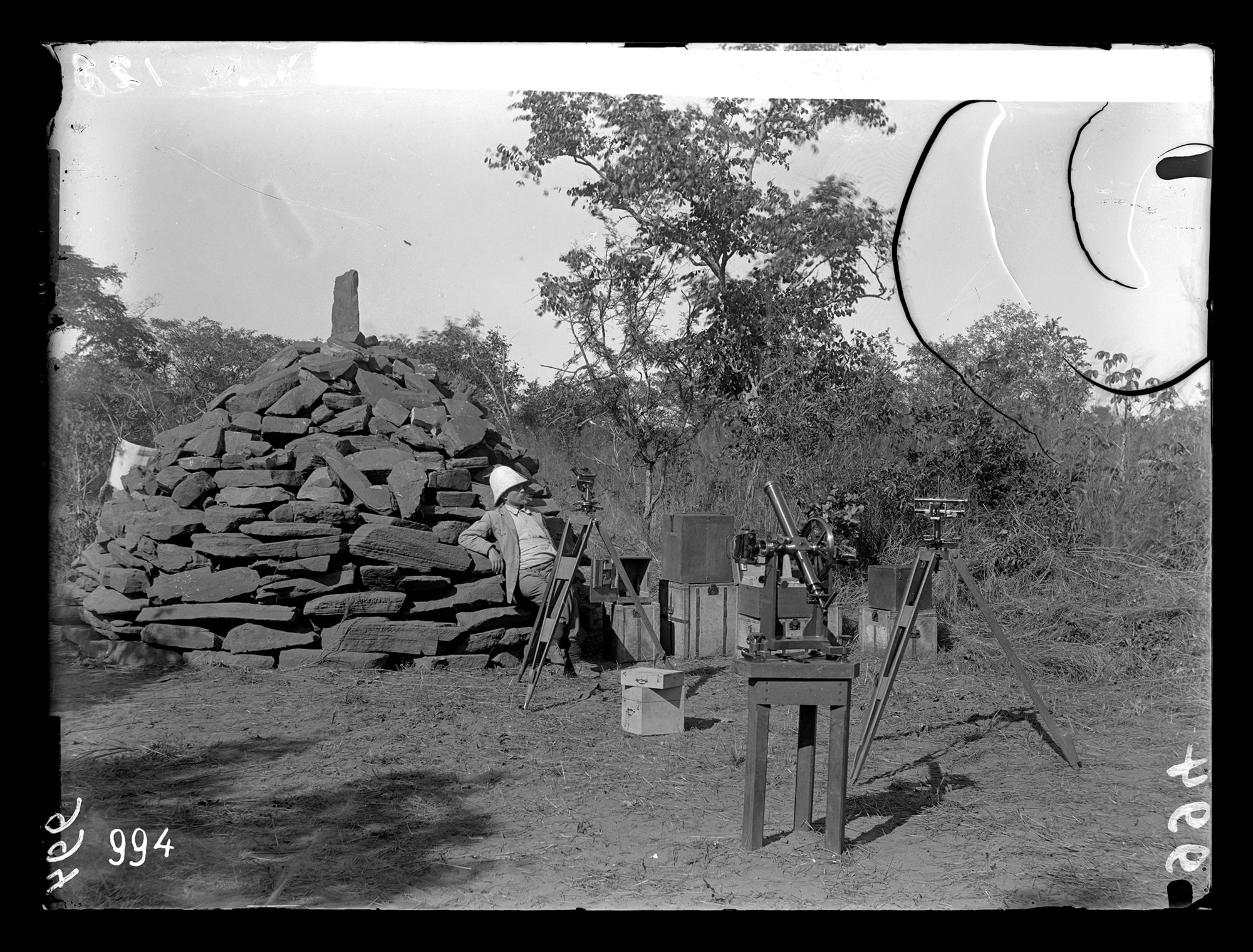

Sammy Baloji then provided some answers, especially in his series “Mémoire” (2004 and 2006) by using the montage technique. He superposed occasional archive photos, depicting individuals or groups who had been connected to this gluttonous modernity, onto the rubble of worksites, the carcasses of factories and the mine galleries he had documented. Decked with symbolic objects (shackles around the neck, ribboned hats, tinted glasses, chechias, the heavy sledgehammer known as nyombolos, etc.), these figures of servitude or of authority formed a prism of power relations in the setting of a colonial mine. As though obliquely lit by a white moon-ray, these ghosts returning from a hereafter which is as binary as their past, have been outlined, intentionally detached from the backgrounds of the images — the dystopic present of an ochre, brown and verdigris— while peopling it as a haunting presence. As for the series “Congo Far West” (2010-2011), it is based on the principle of the diptych. Photos taken by the Belgian explorer Charles Lemaire, while on a mission in Katanga commissioned by the Congo Free State (1898-1900), have been juxtaposed with others by Sammy Baloji, composed to match them topographically or socially. The micro-narratives that are thus created show up the intertwining of timelines and their regimes of violence (Baloji & Couttenier, 2014). To sum up, in these photomontages, history and the present are engaged, but humanity remains frozen in the silence of eternity; and, in the diptychs, the subtly suggested dialogues between the visual and textual signs tip over a stumbling block.

Geodetic marker at Kiubo Falls. Photograph by François Michel taken during the Lemaire expedition to Katanga (1898 — 1900).

Present-day Democratic Republic of Congo. Reproduced courtesy of the artist © Sammy Baloji.

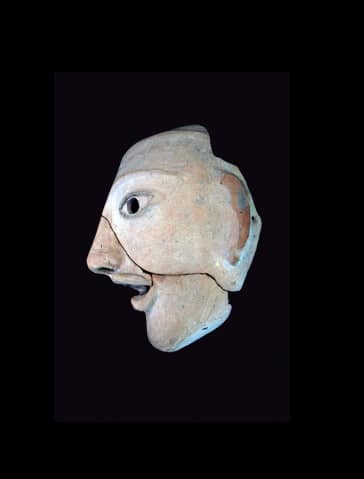

In 2022 Sammy Baloji, at the exhibition at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence devoted to his work, stated his shift towards three-dimensions and triangulation. K(C)ongo: Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues. Subversive Classifications/Fragments de dialogues entrelacés. Classifications subversives is a focal point in the research of the same name that he has been carrying out since 2017 and which his residency at the Villa Medici in 2019 then enriched. The origin of Sammy Baloji’s Italian exhibition lay in four olifants, from the Kingdom of Kongo, dating from the 15th and 16th centuries, three of which had been conserved in the Tesoro dei Granduchi of the Palazzo Pitti, while the fourth was on loan from the Museo della Civilta in Rome. In the 16th century, at least two of these olifants belonged to the Medici’s cabinet of curiosities, probably as gifts to the Pope from the (Christian) King of Kongo.

Thanks to Ezio Bassani and William Fagg, in the 1960s, a corpus of two hundred “Afro-Portuguese ivory” objects — saltcellars, cutlery, dagger handles and olifants — was catalogued, as the work of the sculptors of Sierra Leone, Benin and Kongo, commissioned by passing Portuguese merchants. This production, which began in the mid-15th century with the first sea expeditions along the African coast, came to an end in the mid-17th century with the intensification of the slave trade. But these ivories continued to circulate in Europe from one cabinet of curiosities to another, according to important diplomatic contacts and the taste of the elite for art and luxury. Ceremonial horns, sculpted on elephant tusks, stand as a category unto itself in this corpus. Those from West or East Africa are covered by decorative European motifs, such as scenes of hunting kills, Christian symbols, unicorns or royal Portuguese coats of arms, probably copied from wood engravings or dictated orally by the clients to the artists. As for the olifanti, prestigious objects which were acquired locally, they stand out for a greater abstraction in their decorations, derived from the formal and conceptual repertoire of the place of production, Central Africa, for example (Vogel, 1988) .

The linchpin of Sammy Baloji’s exhibition in Florence was thus an olifant from Kongo, listed in a 1553 inventory as belonging to Cosimo I de Medici. It is one of the seven to be catalogued in the world, and one of the first to enter a European collection. This object has the lateral mouth which is characteristic of horns made for an African clientele, but also a lug for a strap near its tip, showing that it was destined for exportation. Its surface has been treated with an exquisite maestria: six sections of geometric engravings, dominated by spirals, while intersecting chevrons and angular traceries open up additional spaces, overlain with a fractal principle; the object’s cadenced lines seem to project it beyond the limits imposed by its form (Sammy Baloji, Eike Schmidt and Lucrezia Cippitelli, 7:04-7:40, 2022).

Did the presence, the learning and the three-dimensionality of these objects1 incite Sammy Baloji to make a similar projection that transcended planes, which had previously been the favoured basis for his work? “When I started working on the 15th century, it became really difficult to use photos”, he confided in a conversation at the Galerie Uffizi, explaining that essentially these majestic objects already depicted themselves. “The point for me”, he concluded, “was to find a way to create an image from my relationship with the object or from the feeling it generated”(ibid., 45:22- 46:00). To materialise the emotion set off by this Kongo-Portuguese heritage, he created an installation that reconstitutes the horizontal relationship and the interwoven dialogues between Europe and Africa prior to the 17th century. The particular form of didacticism of a cabinet of curiosities, lacking any intention to make an ethnographic classification, inspired him with, among other things, the set titled “Gnosis”, in which period maps appear along with a letter from the King of Kongo to his Portuguese counterpart. He added to them Congolese masterpieces conserved at the Museo di Antropologia e Etnologia in Florence, a Baluba statuette of a woman carrying a jar, for example, thus subverting the classic distinction between ethnography, fine art and contemporary African art.

This selectively plural accumulation did not undermine the unity of the exhibition, which was based on right-angled interlacing, observed on the olifant and then magnified by Sammy Baloji: he turned this into a metaphor for what could be agreed on, during the Renaissance, and what can still be agreed on today — Beauty. This motif of angular interlacing, as seen on raffia “velvets’, also imported from Kongo or Angola, as well as the scarified backs of people and statues, was reproduced by Sammy Baloji on a rug, “The Crossing/La traverse”, which crosses seven rooms of the Andito degli Angiolini at the Palazzo Pitti. This sets off echoes, above all with “Secret Societies”, a series in which Sammy Baloji placed on copper plates the scarifications photographed by an ethnographer2, and “Negative of Luxury Cloth/Négatif de tissu d’apparat”, seven bronze plates on which the designs formed by the weaving of these velvets have been traced out.

In this way, the most emblematic series in the explorations of an artist, who has temporarily given up photography to construct a shared off-field, is made up of fifteen black-and-white paintings in which the motif of interlacing is adopted, shattered and repositioned in rhythmic iterations, according to Derrida’s concept of différance (Sammy Baloji in conversazione, 46:22-46:52).

Exhibited at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 2021, this series interweaves words and worlds, while evoking “Goods Trades Roots” and a loom, Congolese velvets, but also Vasarely’s optical art, or else electronic circuits.

It invites us to take a swan-dive and envisage what hasn’t happened: “What if…?”

Sylvie Kandé

Translated by Ian Monk

1 Three olifants of the same type were chosen for the exhibition “Fragments of Interlaced Dialogues”.

2 This project, begun in 2016, has led to a multimedia installation displayed at Tate Modern, in London, in 2022, “This is where, as you heard, the elephant danced the malinga. The place where they now grow flowers” (Bonsu Osei, 38-41)

Bibliography

Sammy Baloji & Maarten Couttenier “The Charles Lemaire Expedition Revisited: Sammy Baloji as a Portraitist pf Present Humans in Congo Far West” African Arts vol 47, 1 (Spring 2014): 66-81

Sammy Baloji in conversatione con Eike Schmidt e Lucrezia Cippitelli https://www.facebook.com/uffizigalleries/videos/fragments-of-interlaced-dialogues-sammy-baloji-in-conversazione-con-eike-schmidt/1479725152446295/

Bonsu, Osei. African Art Now. 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2022, 38-43

Jewsiewicki, Bogumil The Beautiful Time. Photography by Sammy Baloji. Museum for African Art, New York, 2010

Jewsiewicki, Bogumil “ Photographe de l’absence. Sammy Baloji et les paysages industriels sinistrés de Lubumbashi” L’Homme 198-199 (2011): 89-103

Niarchos, Nicolas “The Dark Side of Congo’s Cobalt Rush”. New Yorker, 24 mai 2021 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/05/31/the-dark-side-of-congos-cobalt-rush

Vogel, Susan (dir.) Africa & the Renaissance: Art in Ivory. Ezio Bassani & William B. Fagg. The Center for African Art, 1988

![sammy-baloji-3[60]](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/sammy-baloji-360.jpeg)

![sammy-baloji-2[82]](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/sammy-baloji-282.jpeg)