Caution: Distraction in Progress

Sep. 21 – Apr. 22

EDITORIALS

Anonymous, Five-way portrait of Marcel Duchamp (at the Broadway Photo Shop in New York), 1917 © Association Marcel Duchamp / Adagp, Paris, 2021

Should this image be taken seriously? Should it be viewed as anything other than playful? All we know is that this five-way portrait of Marcel Duchamp was taken in a Broadway photo shop in front of a hinged mirror, a technique commonly used in photography studios and amusement parks at the time. Henri-Pierre Roché, who had his portrait taken at the same time as his friend, remarked: “It’s quite ugly, but the idea is funny.” Duchamp would say nothing, and would not slip his portrait into his work—not even the proliferatory Box in a Valise (1941). We could get carried away in speculation, and would not be alone in doing so. By tying this thread to that work or this work to that note, perhaps we might ultimately turn this photograph into a cornerstone of Duchamp’s oeuvre. Once again, Duchamp does not ask us to decide. As a precocious champion of “all at once”, he encourages us to take this multiphotograph seriously, precisely because it is nothing but playful.

Étienne Hatt

Laura, directed by Otto Preminger, 1944. USA, 88 min

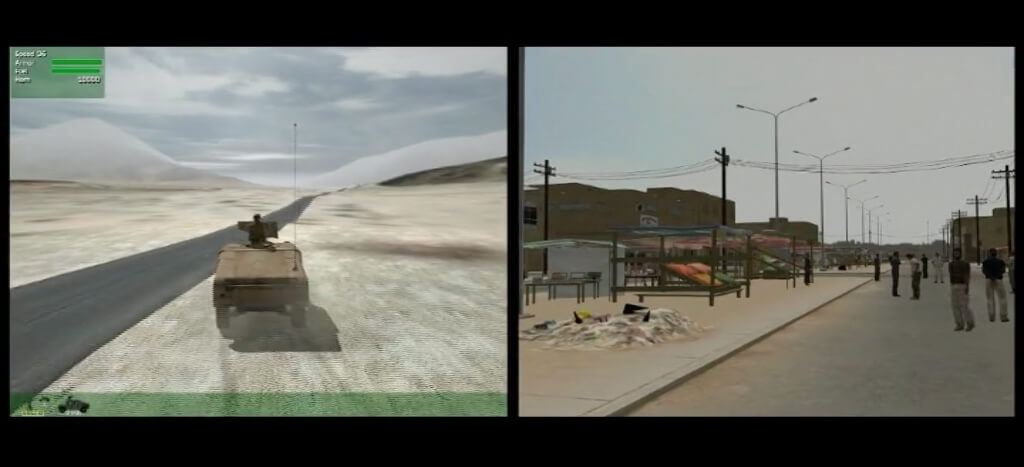

Distraction generally gets bad press: it is collectively viewed as an experience of wasted time, tending to be driven by what are presumably objects of lowbrow or inferior culture. It is conflated with a diversion that is doubly guilty—of hampering our attentive perception of surrounding objects and beings, and of inevitably alienating us by leading us astray from a supposedly noble or high culture. This popular belief reinforces the fixed opposition between “distraction” and “attention”, without considering that the former falls within an attention regime that may be of significant heuristic scope, encompassing knowledge of the self and of the world. Attention may indeed be distracted, incidental or peripheral, when you look at an image in the street, a painting hanging in a museum or a computer screen at home. The circumstance may at times lead us to focus on a seemingly insignificant detail, which might have remained unseen, but which places us on the path of an understanding that we did not anticipate, however nascent or even embryonic. A whole world of meaning then opens up to us, while the stereotypes shaping how we sense or think potentially teeter—including the strongly-held belief as to the inferiority of wandering or distracted observation to an attentive and focused consciousness.

Dork Zabunyan

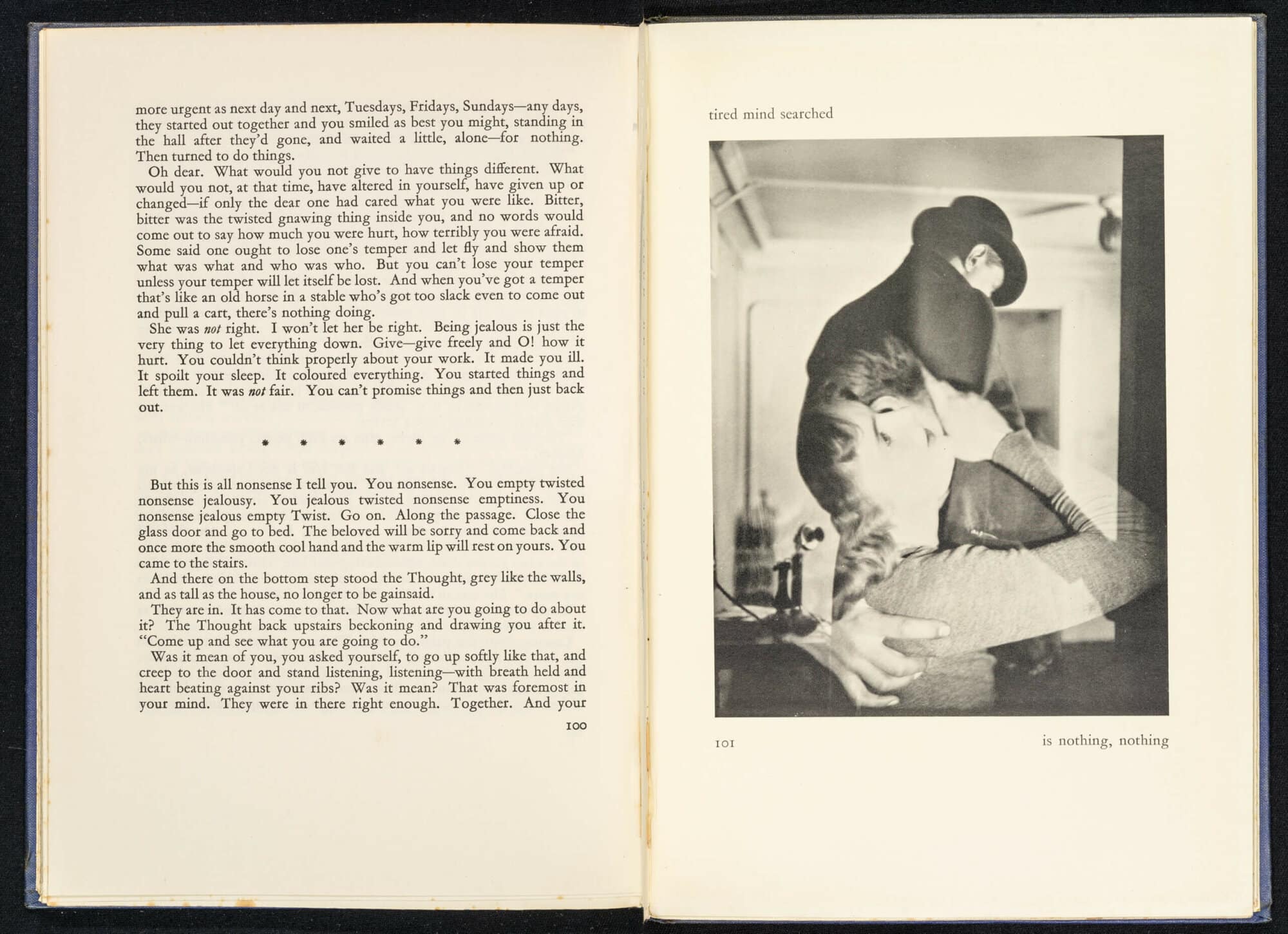

Lance Sieveking and Francis Bruguiere, Beyond This Point, Duckworth, London, 1929. Courtesy University of St Andrews Library, Scotland and Nick Sieveking

Demanding contemplation from our retinas while simultaneously instilling mental diversion in different directions, any image of high or low art inevitably has an oxymoronic relationship with the concept of distraction. The image’s imposing visual presence tries to grab our attention and fight distraction through its magnetic power, but as soon as it succeeds, by piercing our gaze and penetrating our mind, a polysemic dance begins, precisely embracing and propagating distraction. What happens when distraction is among the aims of an artwork? The almost-forgotten 1929 book Beyond This Point by photographer Francis Bruguiere and writer Lance Sieveking comes to mind, as an example of “scripto-visual”1 overload that simultaneously implies and challenges “the modern, distracted mind”2. Photographs that are quite overwhelming and disconnected from the material world aggressively interrupt a stylistically hybrid text, so that the reader, rather than enjoying a moment of relief from complex language, is forced to dissect the image, wrestle with the shapes and imagine what’s gone missing in the sentence.

Federica Chiocchetti, aka Photocaptionist

2 Anne McCauley, in. More than One: Photographs in Sequence, 2008, pp. 46-65.

Franz Wanner, ‘Secret Sites’ series (2018), German Weather I, Helene-Weber-Allee 23 | ca. 2008 to the present (2018)

“Some of the information in this tremendous field, if you look at it carefully, is faintly glowing. And what it’s glowing with is the amount of work that’s being put into suppressing it. So, when someone wants to take information and literally stick it in a vault and surround it with guards, I say that they are doing economic work to suppress information from the world. And why is so much economic work being done to suppress that information? Probably—not definitely, but probably—because the organization predicts that it’s going to reduce the power of the institution that contains it. It’s going to produce a change in the world, and the organization doesn’t like that vision. Therefore, the containing institution engages in constant economic work to prevent that change. So, if you search for that signal of suppression, then you can find all this information that you should mark as information that should be released. So, it was an epiphany to see the signal of censorship to always be an opportunity, to see that when organizations or governments of various kinds attempt to contain knowledge and suppress it, they are giving you the most important information you need to know: that there is something worth looking at to see if it should be exposed and that censorship expresses weakness, not strength.”1

“The way to reveal a secret program might have been merely to describe its existence, but the way to reveal programmatic secrecy was to describe its workings.”2

“I encountered the term state secret several times in my work, and it always seems to be the last question one can ask, and the last answer one gets to it. The last question and the last answer. The end of transparency. Getting to this point, over and over again, I wanted to get closer to it and maybe pass it and get behind it.”3

Aude Launay

2 Edward Snowden, Permanent Record, part 3, chapter 22, 2019, London, Macmillan.

3 Franz Wanner in conversation with the author, July 2018.

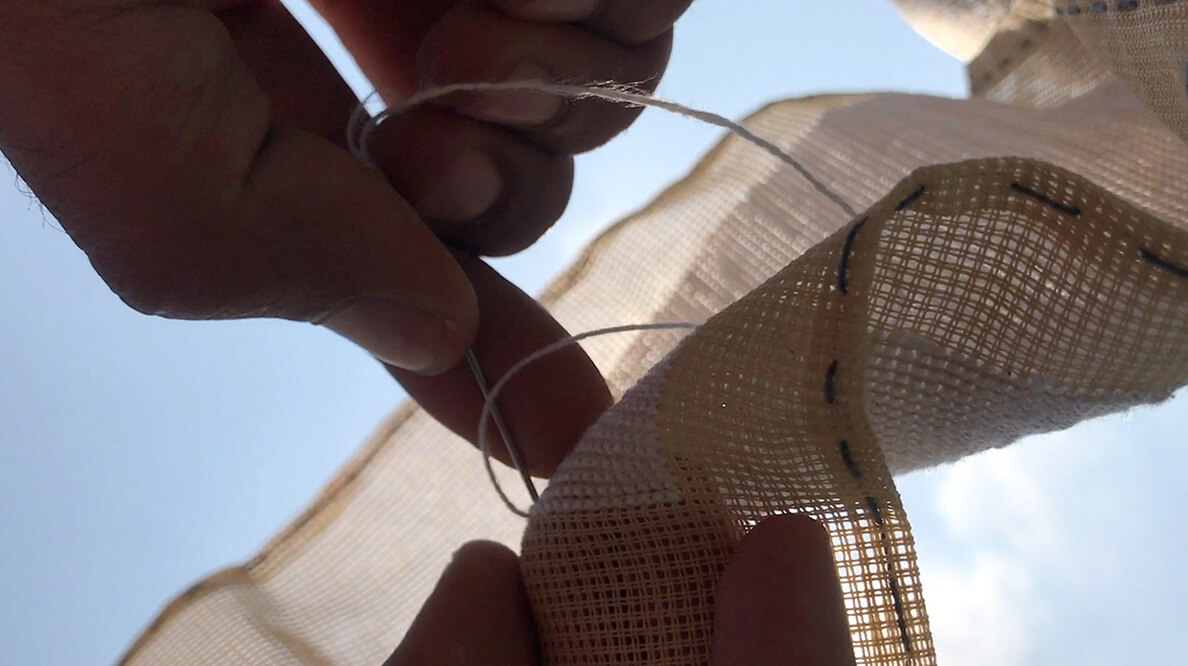

Miléna Kartowski Aïach performs Staying Alive, October 2020, Paris.

Staying Alive : a performance by Miléna Kartowski Aïach

It has been more than a year since the COVID-19 pandemic upended life as we knew it, and in France and elsewhere, people are grappling with the ways in which it has transformed the social, environmental, cultural and political landscape. Over the course of lockdowns in their various forms, daily distraction, whether through the animated discussions over what movies to watch or what books to read, was reserved for those privileged enough to experience a relatively serene lockdown. The call to #stayathome exposed all of the existing social inequalities. The rise in domestic violence in France1 and a number of other countries has been horrific. Many people have been unable to remain at home during the lockdowns, deemed “essential” workers: supermarket cashiers, security staff, healthcare professionals in hospitals, public transportation employees, postal workers, cleaners and janitors, deliverers.

Last April, Elísio Macamo wrote: “COVID-19 is a cruel reminder that crisis is us. As we brace up to look the pandemic in the eye, we would be well advised not to forget what our normal is, namely crisis. History has taught us that you do not master a crisis by setting the return to normality as your goal. You master a crisis by enabling yourself to act whatever the circumstances”2. Which images—visual, sound, theoretical—are able to translate this profound transformation?

The one I am proposing here is an image—with the video from which it is taken—engulfed in the shadow of a night in October 2020, during France’s second lockdown. We can see, but above all hear, a voice embodied by the collective emotion of fear and loss, quivering with the longing to touch others through the empathy of a voice, offering distraction to enable all to feel present as a single body. It is a performance of the song Staying Alive by the writer, performer, singer and anthropologist Miléna Kartowski-Aïach, accompanied on the piano by her neighbor in Paris’s 20th arrondissement. The gravity of her voice leads us to hold our breath for a minute, and to think of this breath that revives us all, so naturally, so easily, and to which access is no longer universal, as Achille Mbembe highlights3.

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez

One political program for the coming time could be defined as distracting the distraction of leisure to fully appropriate its liberating potential—coming in the wake, it should be emphasized, of all that has been dreamed up against alienated labor since its definition, with great precision, by Marx.

![Frédéric Laporte, <i>Autoportrait dédoublé jouant aux échecs</i> [Double self portrait playing chess], 1886. Collection Société française de photographie.](https://jeudepaume.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Frédéric-Laporte-SFP.jpg)