Objects Histories.

Restitution, reproduction, resumption.

apr. – oct. 23

EDITORIALS

July 4, 1984 Boston. A brontosaurus replica is transported via helicopter across the Charles River to the Museum of Science. Photo by Arthur Pollock

When the artist Francesca Catastini sent me this picture by Arthur Pollock, I became addicted to it. This brontosaurus flying over Boston encapsulated my naive visual metaphor of restitution: western colonial dinosaur institutions, in a utopian future, will simply hire helicopters and return the appropriated objects in their collections to where they may belong. I discovered it was a marketing stunt to promote the opening of a new exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Science. How megalomaniacal is that? This led me to think about ethics and curatorial practice. Two women came to mind: Rose Valland and Marion True. The former, a captain and art historian, is known for having secretly recorded Nazi plundering while she was curator at the Jeu de Paume museum in Paris. Thanks to her efforts, nearly 45,000 artworks were returned to their owners before 1950. I’m fascinated by how the aura of such a heroine redeems the haunted spaces of the Jeu de Paume every time I pay a visit. At the other end of the spectrum lies Marion True, the former curator of antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, who was indicted for conspiracy to traffic in illicit antiquities looted from Italian soil and acquired for the museum’s collection. She was also accused by the Greek government of illegal possession of ancient artifacts that were found in her Greek villa. Beyond any quick moralism, I wonder if what unites these two women is a visceral attachment to artistic objects?

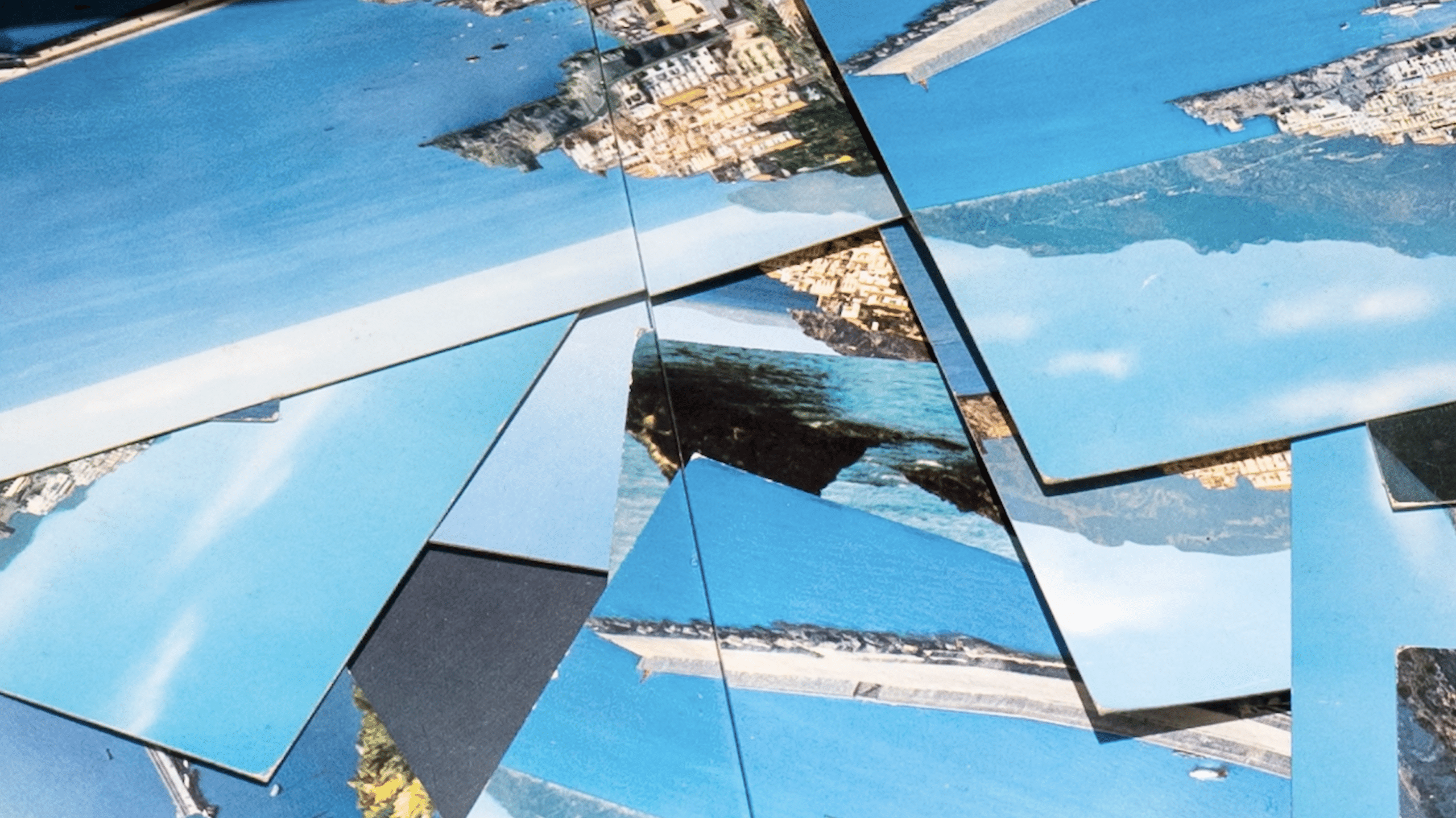

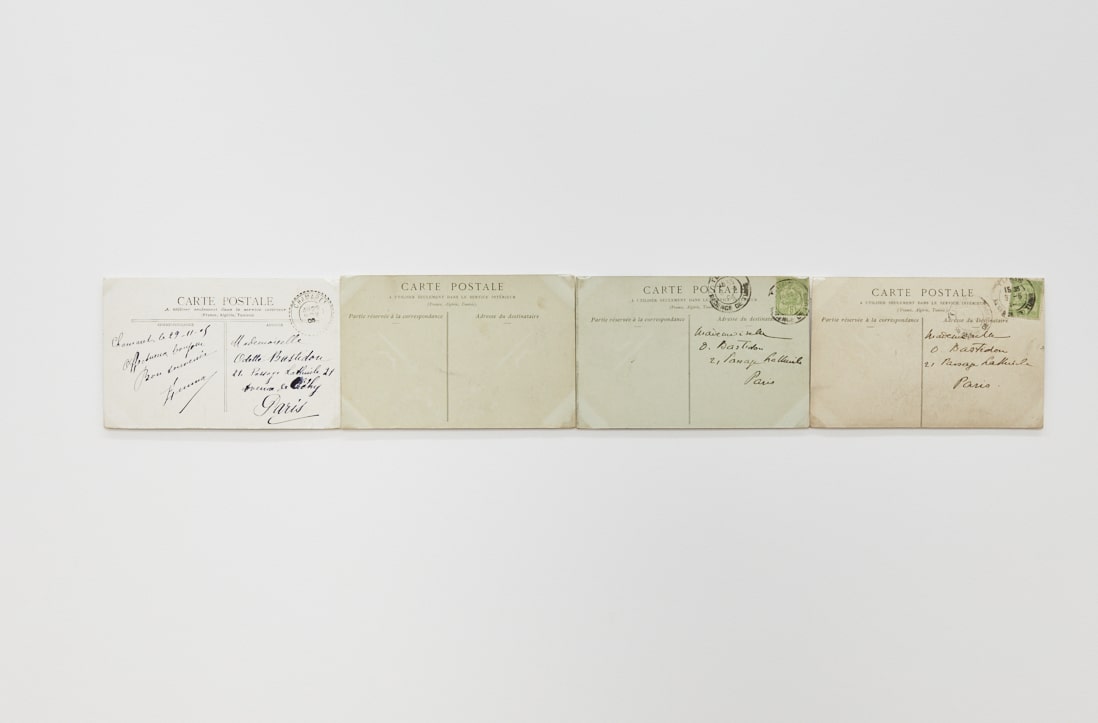

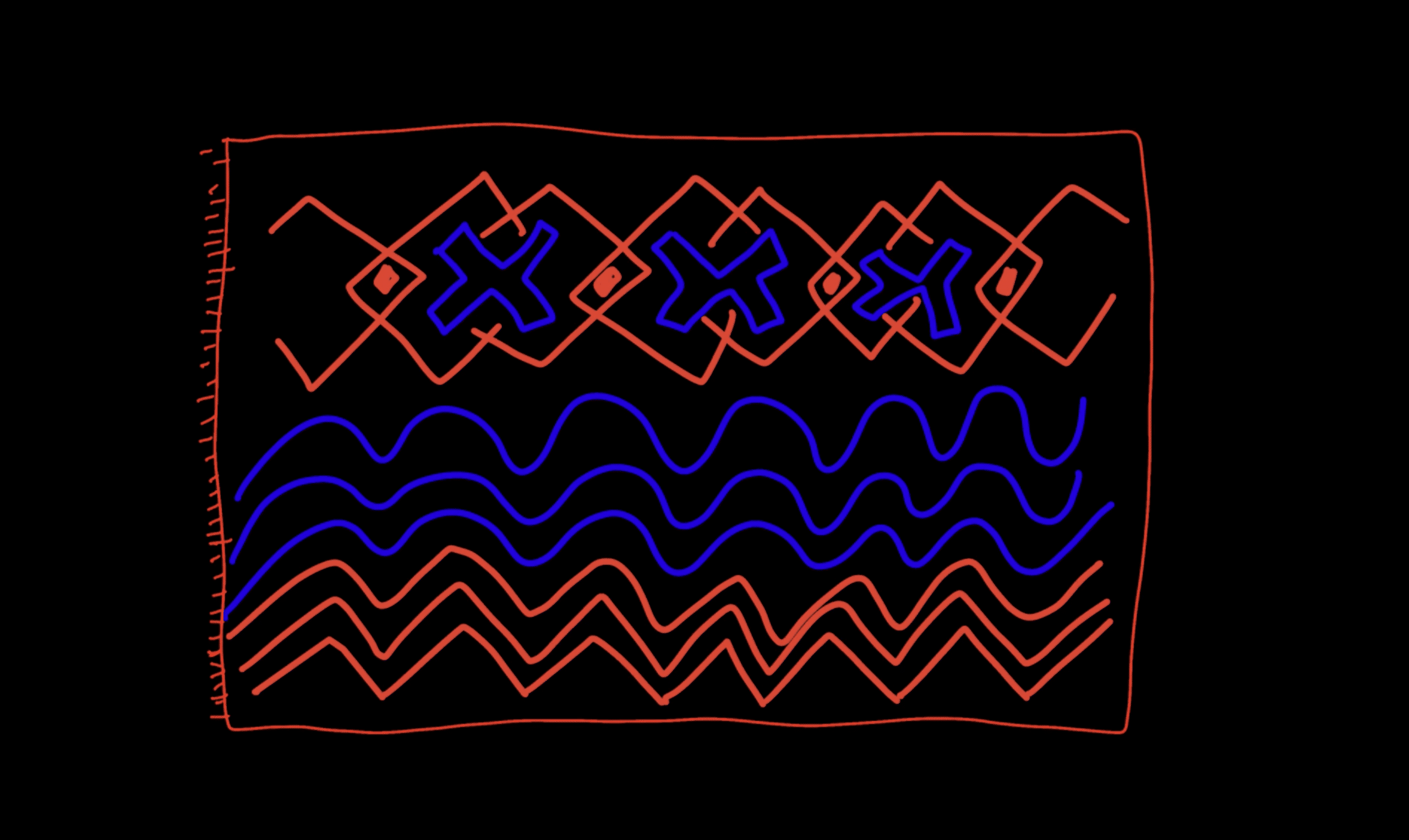

Sophie Kovel, Lieu de mémoire (À utiliser dans service intérieur) (detail), 2017–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist and Petrine, Paris

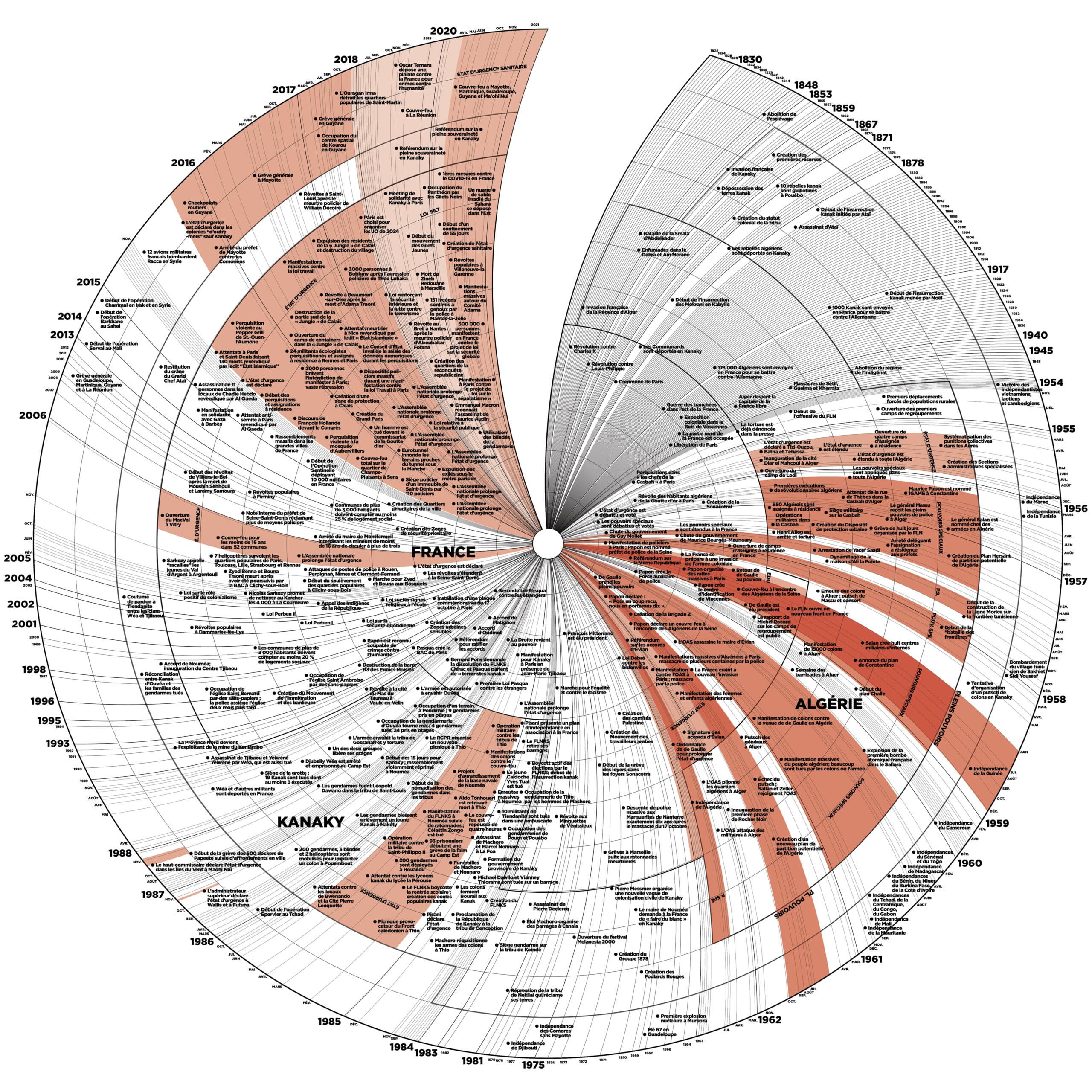

Funny thing, a postcard. A pleasure to send, a joy to receive. A friendly thought from out in the world, a stolen moment from another frame of reference. A postcard lets us collapse an object—an artwork or artifact, a ritual or vista, something the laws of physics or commerce or politics prevent us from bringing home in the flesh—into compact form, barely three-dimensional, ready to breeze across borders. In this way the postcard can also be an index of empire, of its many branching scars. Like this one, one of sixty-seven in Sophie Kovel’s A Long Duration of Losses, authorized for interior circulation only and thus reifying what Kovel calls “the recto-verso of French nationalism and colonialism.” What, we might ask, of objects that do not wish to cross borders? What of objects displaced and repurposed and reduced to a representative likeness? It is by becoming art that objects may transcend our earthly limitations. But it is also by being stolen, sometimes, that they become “art” in the first place.

Daniel Levin Becker

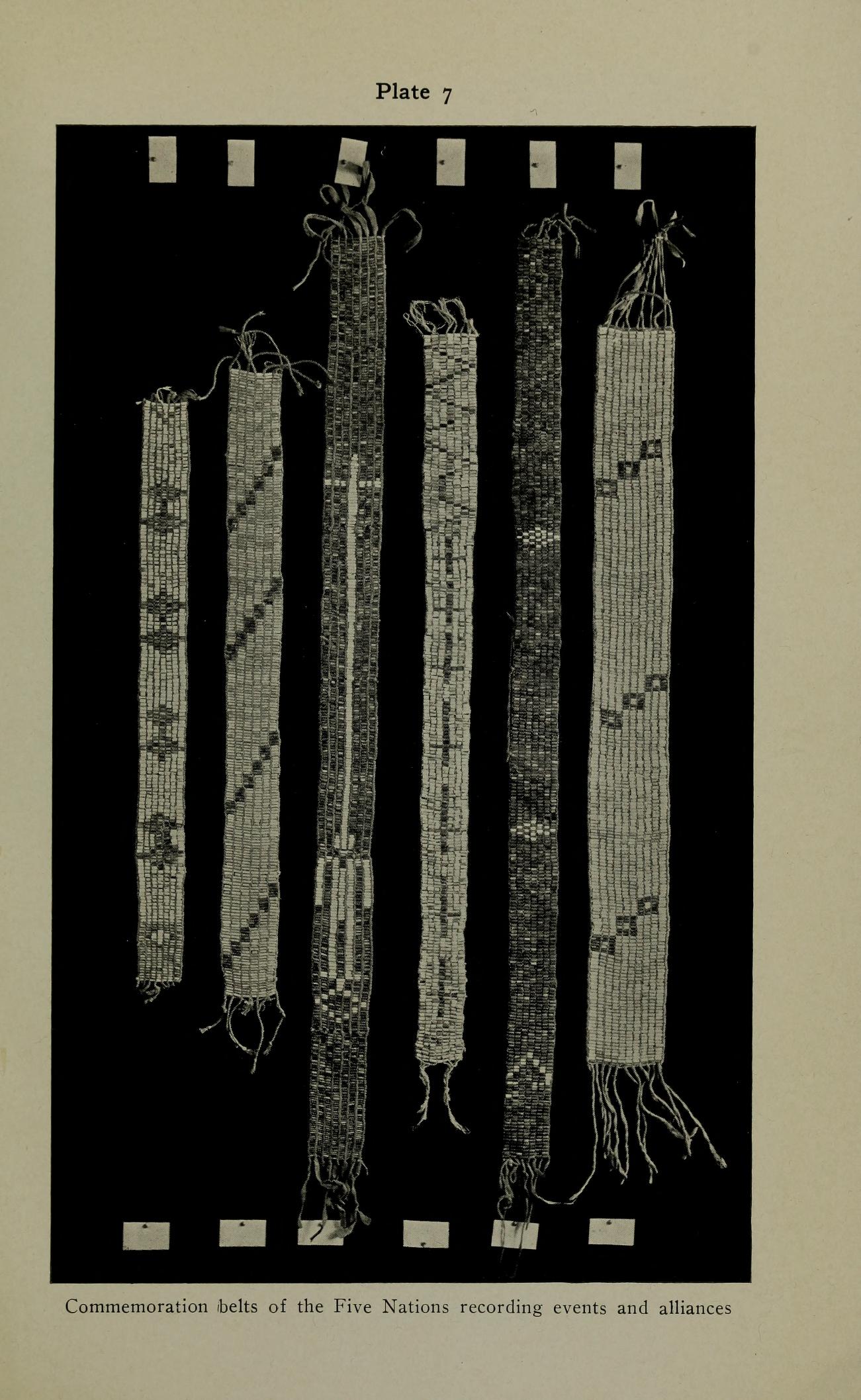

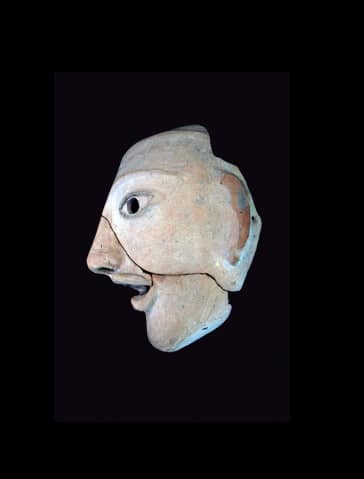

Patina, dust, wounds, praise: objects travel too and bear burdens.

They may be mute, but in the manner of great trees blown away, oracles in any state. Aloof, they stabilize movement and thought as time unfolds; in their rigidity, calling upon the desirous gaze, the grasp that cherishes, and ravishes; teaching the world what-it-is-to-be-human. See Hadrian next to the great unchanging statues restituting the beauty of motions to him! Leiris restituting Dyabougou, where, intoxicated/sickened by his omnipotence, he appropriates fifteen kilos of sacred “shapelessness”!

Restitution: the arts’ non-accessory issue. Costly, moreover: the bird is killed to be reproduced, recalls Karen Houle. Still life, nature morte.

Can the trauma of imperial collection be repaired? This particular restitution cannot be linear, as objects drift, ramble. And sending these once-revered, perhaps still-reviled objects back to a said place of origin calls into question the notion of resumption/take back.

Let the Boli travel! replies Abderrahmane Sissako.

Sylvie Kandé

Thomas Demand, Daily #21, 2013, Framed Dye Transfer Print, 59,8 x 45,4 cm © Thomas Demand, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn / ADAGP, Paris

This is not a bar of soap, but its pale imitation. In reality, just like the pristine bathtub rim upon which it sits, and the wall corner in which the tub is tucked, it is made of paper. Nevertheless, this honey-colored illusion, created from scratch by Thomas Demand based on a photo archived on his phone, elicits an immediate and familiar sense of gentle ennui. Objects tickle memory. Long after evacuating their function, their original state, they preserve the traces of their use, the memory of gestures and people. Affects and cultures mingle and are fixed upon the items inhabiting our shared spaces. Some are practical; others, devoid of apparent qualities, settle for being owned. And then there are the ones that are thrown out, and those that will likely outlive us, to which we are more strongly attached. Talismans, tools, personal belongings and more – these signs of the times draw gazes all around, as seen in the films and photographs gathered here.

Virginie Huet

This ivory Venus, discovered in 2008, is the oldest attested sculpture resulting from human will. The Venus of Hohle Fels, ca. – 40,000 years. Prehistoric Museum Blaubeuren, Germany © Hannes Wiedmann/Urmu.

If our societies are to some extent built based on the meaning and value granted to objects, what are the implications for the continuity of their deeper meaning, when they are uprooted, become invisible or are given a new narrative? What experiences, forgotten or unresolved, do these objects recount? When they reemerge from the past, what might they tell us about the present?

In their work, many contemporary artists look to the trajectories taken by these items that surround and define us, and endeavor to restore the ties they have with their places of origin. Using approaches encompassing anthropology or speculation, they explore how an object might be capable of conveying another type of knowledge – tactile, emotional or interpersonal – by working performatively with it, outside the realm of any historical, colonial or institutional discourse to which it had perhaps once been appended.

Adam McKay, Don’t Look up, 2021 © Paramount Pictures / Adam McKay

The high-speed production and circulation of images today is inseparable from their incessant reuse, accelerated reproduction, and what is incautiously referred to as their “sharing”. But the problem does not lie strictly in this immeasurable quantity of visual signs all over the surfaces of equally omnipresent screens; it is also rooted in how image arts appropriate so-called popular imagery transmitted on these same audiovisual channels, including music videos, ads, fragments of anonymous videos, news parodies and more. The question we wish to raise here concerns the fate awaiting this composite imagery in artistic practices – from films making novel reuse of it to a photograph revealing its consensual aspect, or a video installation imitating it to question its spectacular dimension. Has culture deemed low brow (television, videogames, images disseminated via social media, etc.) been taken hostage by another culture that considers itself superior? Or are there cases in which the former is received without disdain or condescendence, the potential condition for a new and distant relationship to the prevalent reception of its images? In other words: how might an image arts esteem or consider such vastly heterogeneous visual and sound material, which, to say the least, is not always worthy of esteem?

Dork Zabunyan

A visitor in the Thomas Demand's exhibition at the Jeu de Paume. Photography Bénédicte Bonnet Saint-Georges (@benebsg), 2023

Exhibitions are a key moment in the life of artworks. For many of them, this is an opportunity to leave their repository and start conversing with their neighbors. How can photography document this moment? Exhibition views – which I’ll explore through various angles for this issue of PALM, calling upon a theorist, a practician and an artist – was long a professional practice strictly intended for archives, publishing or teaching. These days, social networks show an extensive amateur output with poor-quality technical and aesthetic standards (distortions, reflections, terrible white balance), but illustrating new and purposefully quirky uses around exhibition views. This photograph, taken at the Jeu de Paume in front of Thomas Demand’s Copyshop (1999), posted on Instagram by benebsg, indicates other relationships – no longer between the works, but this time, between the works and visitors. It is no longer a question of reproducing or restituting how they are shown, but of reusing of them, in the sense of reclaiming them.

Étienne Hatt

Claes Oldenburg, Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks, 1969-74, Yale University. Photo © Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio – Courtesy Pace Gallery

Claes Oldenburg squeezes his tube of toothpaste. He empties the object of its content. Freed from its servile condition, it begins to levitate. Once emancipated, objects follow their natural slope: they relax, stretch out, deflate. It should be noted that they often tend to soften, or swell excessively, demonstrating the mastery over space they hold within. In taking on new dimensions, they adopt an impulse-driven anthropocentrism – evidence indeed that what matters is not so much their quality, as the interest shown in them. The Yale University campus features an outlandish monument depicting a tube of lipstick on tank caterpillar tracks: Lipstick Ascending on Caterpillar Tracks, 1969. The object could be perceived as a plea for students to make love, not war. Getting closer, it might be wondered what sort of weapon the lipstick represents, and what danger it might entail for us. Asked about this work, a university professor, himself a multidimensional man, claimed that works like Oldenburg’s were made possible by the fact that the revolution had taken place, even though nobody had noticed.

Damien Guggenheim

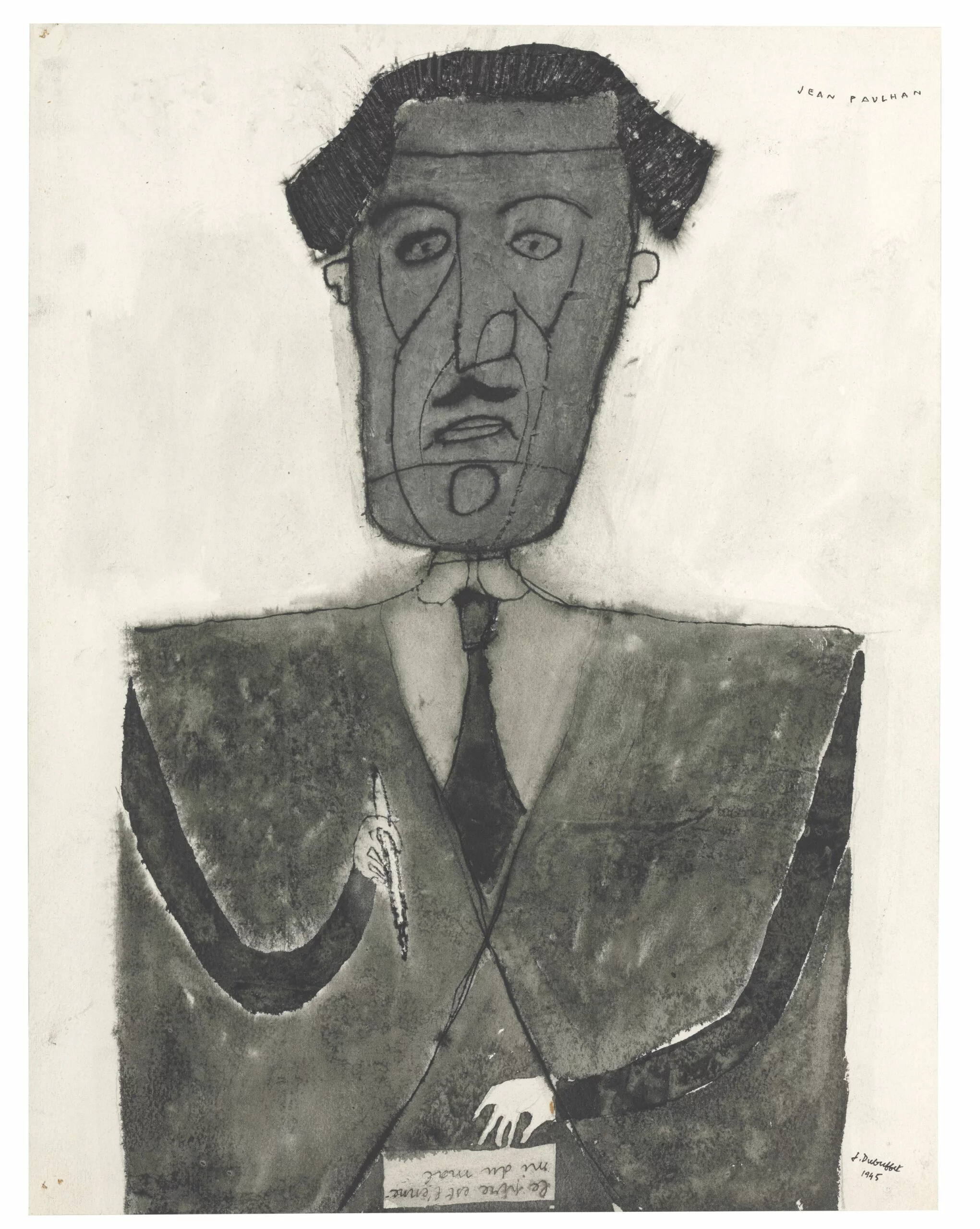

Photography Simon Birman, 2012

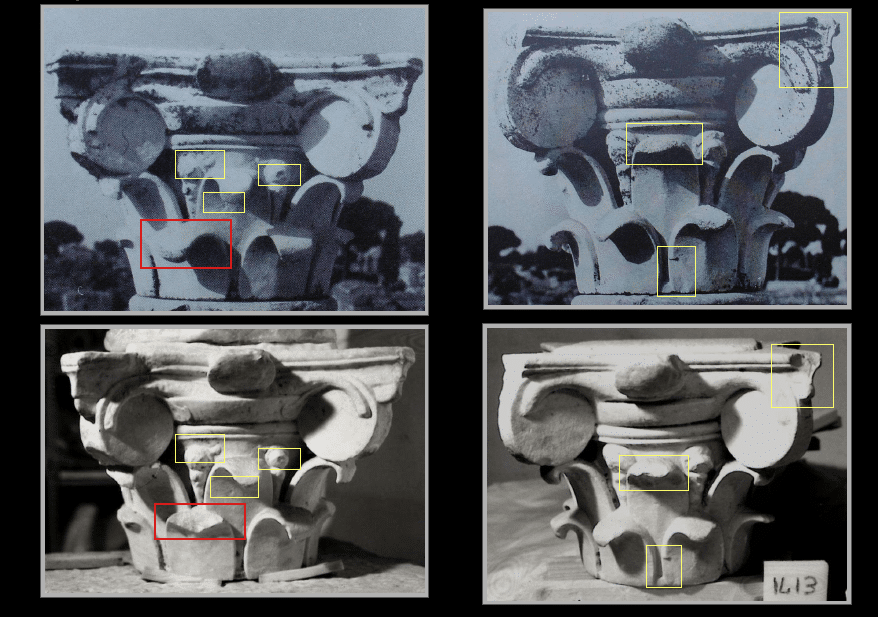

The number of artworks continuously circulating around the world is staggering – measured in billions, in market transactions, loans, borrowings and movements, as well as in looting, theft and despoliation. Museums are packed with works “acquired illegally”. The pressing question in the age of postcolonialism, of multiculturalism and the recognition of the rights of peoples to manage their own “cultural heritage”, is that of their “restitution”. This is a complex issue, wherein, in my opinion, the ontological status of works collides with their cultural or social status. Why not replace stolen works or those returned to their rightful owners with copies, 3D prints or technical reproductions? No, the original is what is coveted, and the original must return to the right place. But what place is this, in fact? Some will say that it is where proper conservation conditions for the work can be ensured; others will argue for its country of production, in the hands of the ethnic group of its artist, or of its heirs. What can actually be said with certainty? My belief is that the enhancement of the original is as inseparable from the mechanisms of appropriation as the front and back of a sheet of paper.

Joëlle Zask

Editorials translated by Sara Heft

Through aesthetic desire, the eye stylizes the perceived, then returns to the observer her or his own investment.