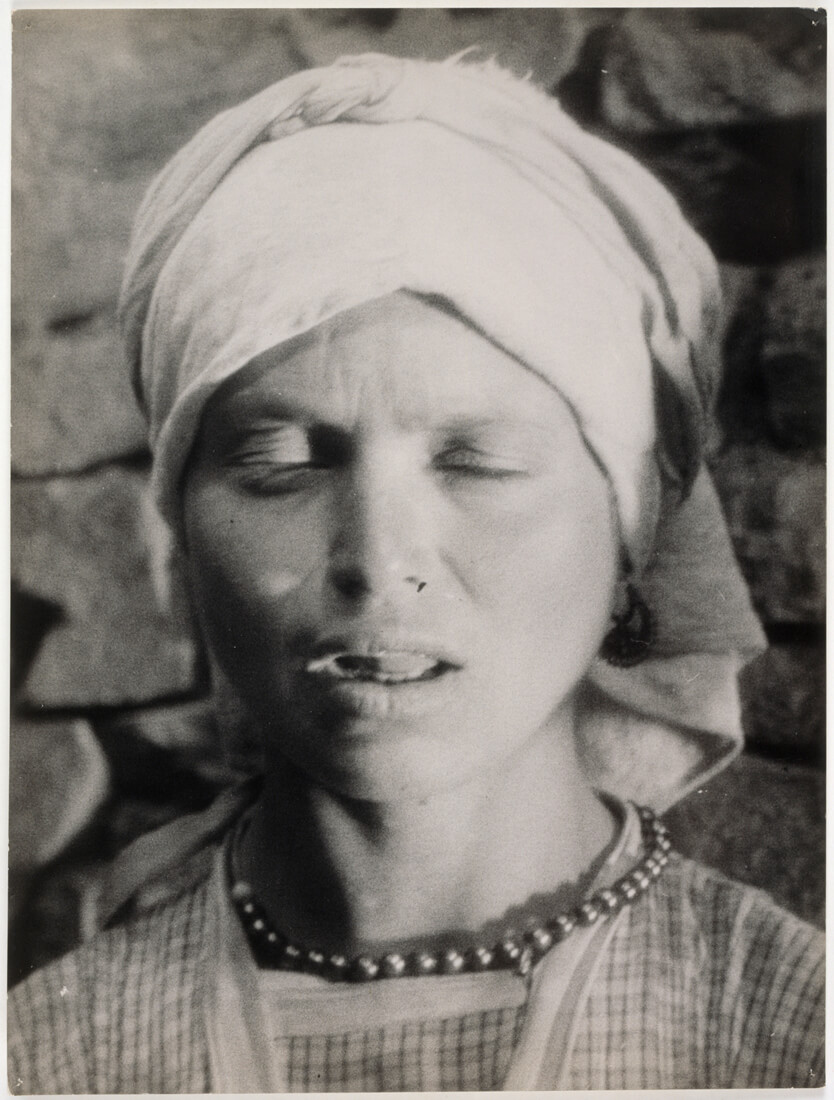

Eli Lotar, Untitled, vintage gelatin silver print, 22.8 x 17.9 cm, gift of Anne-Marie and Jean-Pierre Marchand 1993, Center Pompidou collection, Paris, MNAM-CCI © Eli Lotar

Archive magazine (2009 – 2021)

Jordana Mendelson : Eli Lotar's Dissident Lens in Luis Buñuel's Las Hurdes: Land without Bread

Luis Buñuel's Land without Bread (Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan), (1933) is a searing documentary about the geography, inhabitants, and lifestyle of the western region of Extremadura, Spain, called Las Hurdes.

The film alternately revisits and challenges conventions for representing rural Spain. Prior to more recent revisionist histories of the film, scholars had generally interpreted the film’s content through a formal analysis of its structure, which had severed the film from the complex history of its production and reception in Spain. When the film is considered in relation to its historic and political context then the disruptive potential of the film’s subject (1930s Spain) and the versatile cinematographic work of the film’s cameraman (Eli Lotar) take on greater significance. Indeed, the film is marked by Lotar’s transposition of an urban-based dissident, critical realism onto impoverished, rural Spain, which transforms a region that had been over represented in the press for years (as perhaps the most visible and recognizable example of rural neglect) into a site of dissonance and disruption.

Opening sequence with map of Spain’s border with Portugal, scene from Luis Buñuel, Las Hurdes: Land without Bread, 1933. Reproduced with permission from Les Films du Jeudi.

Even the briefest chronology of Land without Bread demonstrates its intersection with the shifting political terrain of Europe and especially Spain’s Second Republic during the 1930s. The evolution of the Republic’s programs and policies had a direct impact upon the film’s production and reception from 1932 to 1937. Buñuel and his crew (Paris-based Lotar and co-writer Pierre Unik and Spanish educator-activist Rafael Sánchez Ventura) made a preliminary trip to Las Hurdes in September 1932, coinciding with the early years of the Republic’s Socialist government. The film was shot on location from 23 April to 22 May 1933. Buñuel edited the film in Madrid in May and presented it to the press in December, after which it was censored by the newly elected, more traditionalist government. Despite this censorship, he and Unik completed the final script in March 1934. Two years later in April 1936, following the election of the Popular Front government in Spain, the film was officially authorized for viewing. In December 1936, during the Civil War, it was edited with sound in French and English with funding from the Spanish embassy in Paris.

Land without Bread situates at least three modes of documentary in dialogue: institutional (the film’s literary and historic sources), objective (the social realist leanings of some of the film’s supporters and participants), and dissident (the aesthetic practices of Lotar in relation to those of French surrealism). The influence of academic sources like the French writer Maurice Legendre’s 1927 doctoral study of Las Hurdes over Buñuel and his crew is well known. That thesis was based on repeated trips made to Las Hurdes by Legendre, the most famous of which was the one in 1922 in which he was accompanied by Doctor Gregorio Marañón (who according to Buñuel was one of the film’s most vocal opponents) and King Alfonso XIII; that trip was covered widely in the illustrated press and recorded in a documentary style newsreel. Just as images of the King’s trip circulated broadly, so too did film stills from Land without Bread, especially in Spain’s leftist press, which should not surprise historians given the crew’s political affiliations: Buñuel, Unik, and Lotar were sympathetic to Communism, while Sánchez Ventura and the film’s producer, Ramón Acín, were Anarchists.

Just weeks after filming, stills from Land without Bread appeared on the front and back cover of the inaugural number of Octubre : Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (June-July 1933), published by writers Rafael Alberti and María Teresa León, who had accompanied Buñuel during one of his preparatory trips to Las Hurdes and had recently returned from a trip to the Soviet Union. While they accepted the presence of a politicized message and an aesthetic parallel to that practiced in the Soviet Union in the film, Spain’s leftist artists seemed oblivious to the film’s connection to the dissident practices of French writers like Georges Bataille and the Parisian magazine of ethnography, art, and culture Documents : doctrines, archéologie, beaux-arts, ethnographie (Paris, 1929-1930). For writers like Alberti and León, there was no distance between what they saw in Las Hurdes and how it was represented in Buñuel’s film: in Octubre the film stills were presented as objectively reproduced facts.

Despite the political efficacy that comes from reproducing images from the film as objective truths, Land without Bread juxtaposes different visual perspectives and historical references, thereby creating a more contradictory relational scheme. The film demonstrates to the viewer that it is a composite of past and present visual references. The flow from one image to another is not smooth: there are jumps in the cuts and disruptions between sound and image. Buñuel reveals his sources and himself as an agent in constructing the film’s narrative. For example, when watching the sequence on the fall of a goat into a canyon, the viewer sees the smoke from the crew’s rifle shot. Shock is registered in the structure of the film, in the erratic referencing of past visual sources, and in the vertiginous movements of the camera between shots. It is felt in the spaces between the shots, in the visibility of the suturing of sequences to each other, and in the camera’s obsessive treatment of Las Hurdes as a site of abjection, as a site where the categories of difference are erased. This aspect of the film, which brings to the fore what Georges Bataille would describe as the informe, the formless, or that which defies categorization, connects the film to the earlier visual practices of Lotar and dissident surrealism.

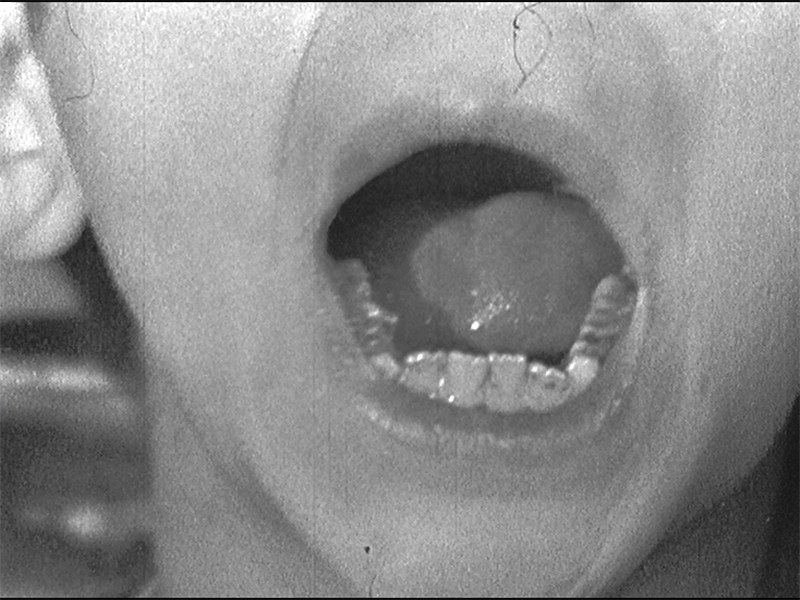

Luis Buñuel, Las Hurdes: Land without Bread, 1933. Sequence reproduced with permission from Les Films du Jeudi.

Conserved in The Eli Lotar Collection at the Centre Georges Pompidou, are some unpublished photographs taken by Lotar of the inhabitants of La Alberca, one of the more prosperous villages in Extremadura that the film crew visited before moving on to Las Hurdes. They are surprising in their replication of nineteenth-century conventions for photographing types. They come closest, in fact, to the photographs taken by such nineteenth-century photographers in Spain as Jean (Juan) Laurent and his successors, whose images of regional pairs established a model for presenting Spain’s diverse types and dress. Laurent’s photographs were published widely at the turn of the century, especially in the Madrid illustrated magazine Blanco y Negro. Although the dress and customs of the Albercans form a section of the completed film, Lotar did not include these more imitative views. Rather, in the film, the inhabitants and their customs are situated within a specific ritual context: the Albercans are preparing for a rite of passage for young men. Comparing the unpublished photographs with the portrayal of the Albercans in Land without Bread it would seem as if these still photographs formed part of Lotar’s rehearsals for different approaches to the problem of photographing the Hurdanos, from the institutional traditions of the nineteenth century (his sources) to a revised vision of those norms.

The visual heterogeneity of Land without Bread includes references to Lotar’s own past projects, for example when he appears to cite from the earlier work that he and his studio partner Jacques-André Boiffard published in the Parisian magazine Documents (1929-30). With financial support from the Vicomte de Noailles (the same patron of Buñuel’s L’Âge d’or), Lotar and Boiffard set up and ran Studios Unis on the rue Froidevaux in Paris from 1929 to 1932. In addition to their portrait work, both frequently published photographs to accompany Georges Bataille’s articles and “critical dictionary” entries for Documents. The recurrence of this imagery in Land without Bread is apparent throughout the film. In the magazine’s sixth number, three of Lotar’s photographs were published to illustrate « Bataille’s dictionary entry », for the Parisian slaughterhouses. Lotar’s brutally frank images of the underbelly of Parisian life reverberate in his camera work for Buñuel, especially in scenes showing the ritual beheading of the cock as a rite of passage for Albercan men, the abstracted horror and provocation of a putrefied donkey, and finally the scopic drive to capture a goat’s fall into a ravine.

The integration of imagery that accompanied Bataille’s writings in Documents appears with persistence during the sequence of a young girl found lying by the side of a road with an infection. The camera quickly moves to an extended shot of the girl’s mouth. The extreme close-up recalls Boiffard’s photograph for Bataille’s entry “Mouth”. Bataille saw the closed mouth “as beautiful as a safe”: secure, sutured, and seamless. The open mouth, on the other hand, was a sign of disruption, infection, and bestiality.

The gaping gesture of the mouth in Land without Bread, like the photographs by Boiffard and Lotar in Documents, stands for a syntactic rupture. Unlike Buñuel’s earlier films, Un Chien andalou and L’Âge d’or, where the editing process is made visible either through symbols or shifts in style, in this film there is no tool or sign of the editing process. It is only through the mediation of Bataille’s definition of the open mouth as a wound or fracturing of the visual field that the process of splicing and juxtaposition is invoked. Each reference to a particular source, each sequence, becomes a discrete document that breaks up the film’s structural cohesion and lays bare its fabrication.

Another series of close-up photographs by Boiffard, some of which accompanied Bataille’s entry “The Big Toe,” further reinforces the relation between Documents and Lotar’s camerawork in Land without Bread. In one sequence, the camera takes a visual inventory of the feet of the Hurdano school children. After the narrator describes the tattered Hurdano clothing, while showing the blank expressions of the children as they stare into the camera, Lotar pans a row of feet for a significantly longer amount of time than he dedicates to almost any other scene. Among the children’s feet, one pair stands out as an echo of Boiffard’s illustrations for “The Big Toe.” But in this case, the foot’s deformity is real, not a distortion revealed by the alienating effects of the camera.

Luis Buñuel, Las Hurdes: Land without Bread, 1933. Sequence reproduced with permission from Les Films du Jeudi.

In Land without Bread, thanks to Lotar’s dissonant camera work, a leveling takes place in which the heterogeneous is allowed to enter and interact with the film’s institutional sources. The porous boundaries between various kinds of documents, between production and reception, between objective and dissident documentary allow for multiple misidentifications. Both geographic and temporal overlay take place. The film’s various disjunctive moments, in large part caused by the excess of documents, is further accentuated by the identification between the poverty of the film’s subject matter, the film’s structural porousness, and its material qualities. Noticeable in watching some copies of the film are the glitches, dust, and scratches that constantly assault the image plane. The borrowed equipment used to film Land without Bread might partly explain its poor quality. It was perhaps compounded by the fact that the film was edited without a moviola, in a short period of time, on Buñuel’s kitchen table. Because Las Hurdes was considered at the time the poorest and most provincial of Spanish towns, the film’s technical execution parallels the physical conditions of the region and its inhabitants. Instead of causing disruption within a rural context, the aesthetic strategies previously used to reveal the base and informe of the city are here employed in the representation of the Spanish landscape, returning those elements which are most disturbing in the country back to the city. Through a careful dissection of the film’s visual citations, Lotar’s activist use of his camera to wrench realism away from a passive mode of testimony becomes evident. In fusing together references from institutional histories of Las Hurdes and conventions from documentary filmmaking with the citation of his own visual production from just a few years prior, Lotar succeeds in creating for Buñuel and his crew a visual collage that breaks down the sanctity of distance by soiling his lens with Spain’s rural informe.

Jordana Mendelson (New York University)

This is a much abbreviated version of a more thorough treatment of Land without Bread which appears in the author’s “Contested Territory: The Politics of Geography in Luis Buñuel’s Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan », Locus Amœnus (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) 2 (1996) : p. 229-242 ; et Documenting Spain : Artists, Exhibition Culture, and the Modern Nation 1929-1939, University Park, PA : Penn State University Press, 2005, p. 65-91.